Partner Renée Vivien, Élisabeth de Gramont, Romaine Brooks

Queer Places:

Bar Harbor, Maine, Stati Uniti

1626 Rhode Island Ave NW, Washington, DC 20036, Stati Uniti

97 Cadogan Gardens, Chelsea, London SW3 2RE, Regno Unito

4 Rue Chalgrin, 75116 Paris, Francia

20 Rue Jacob, 75006 Paris, Francia

Les Ruches, 10 Avenue des Carrosses, 77210 Avon, France

Passy Cemetery, 2 Rue du Commandant Schloesing, 75016 Paris, Francia

Natalie

Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American

playwright, poet and novelist who lived as an

expatriate in Paris. She appears as Florence Temple Bradford (Flossie) in

"Idylle Saphique" (1901) by

Liane de Pougy; as Vally (Lorely

in the second version) in "A Woman Appeared to Me" (1904, 1905) by

Renée Vivien;

Laurette in "L'Angel et Les Pervers" (1930) by

Lucie

Delarue-Mardrus; Dame Evangeline Musset in "Ladies Almanack" (1928) by

Djuna Barnes;

and Valerie Seymour in "The Well of

Loneliness" (1928) by Radclyffe Hall.

She is also the the basis for a character in "Lettres à l'Amazone" by

Rémy de

Gourmont.

Natalie

Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American

playwright, poet and novelist who lived as an

expatriate in Paris. She appears as Florence Temple Bradford (Flossie) in

"Idylle Saphique" (1901) by

Liane de Pougy; as Vally (Lorely

in the second version) in "A Woman Appeared to Me" (1904, 1905) by

Renée Vivien;

Laurette in "L'Angel et Les Pervers" (1930) by

Lucie

Delarue-Mardrus; Dame Evangeline Musset in "Ladies Almanack" (1928) by

Djuna Barnes;

and Valerie Seymour in "The Well of

Loneliness" (1928) by Radclyffe Hall.

She is also the the basis for a character in "Lettres à l'Amazone" by

Rémy de

Gourmont.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, no admirer of lesbians or feminists, depicted Barney in Tender as the Night as someone whom his hero, Dick Diver, had to go see because she wanted to buy some pictures from a friend of his who needed the money. “You’re not going to like these people,” he warned Rosemary, the young American friend falling in love with him. And inside, Rosemary is besieged by a “neat, slick girl with a lovely boy’s face” until drawn into conversation with “the hostess,” “another tall rich American girl, promenading insouciantly upon the national prosperity.”

One of the most unusual aspects of the Stettheimers’ salon was the large number of their gay, bisexual, and lesbian friends and acquaintances, who were comfortable being their authentic selves among their straight friends. Several of the sisters’ closest friends, including Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Henry McBride, Virgil Thomson, and Baron Adolph de Meyer (married to a lesbian, Olga Carracciolo) were homosexual; Carl Van Vechten, Cecil Beaton, and Georgia O’Keeffe were bisexual; Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks were lesbians; and Alfred Stieglitz, Marcel Duchamp, Gaston Lachaise, Marie Sterner, and Leo Stein were heterosexual. This open, natural mix of friends with different sexual preferences continued when Stettheimer held salons in her studio in the Beaux Arts building in midtown Manhattan, although later in life she also had parties where most of the guests were strong feminist women.

Natalie Barney not only wrote a prolific record of her own lesbianism (as did Colette, Renée Vivien, and Radclyffe Hall) but also served as a fictional model of lesbianism in an astonishing number of works by other writers of the belle époque, appearing in works by Liane de Pougy, Renée Vivien, Ronald Firbank, Remy de Gourmont, Colette, Djuna Barnes, Radclyffe Hall, and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus.

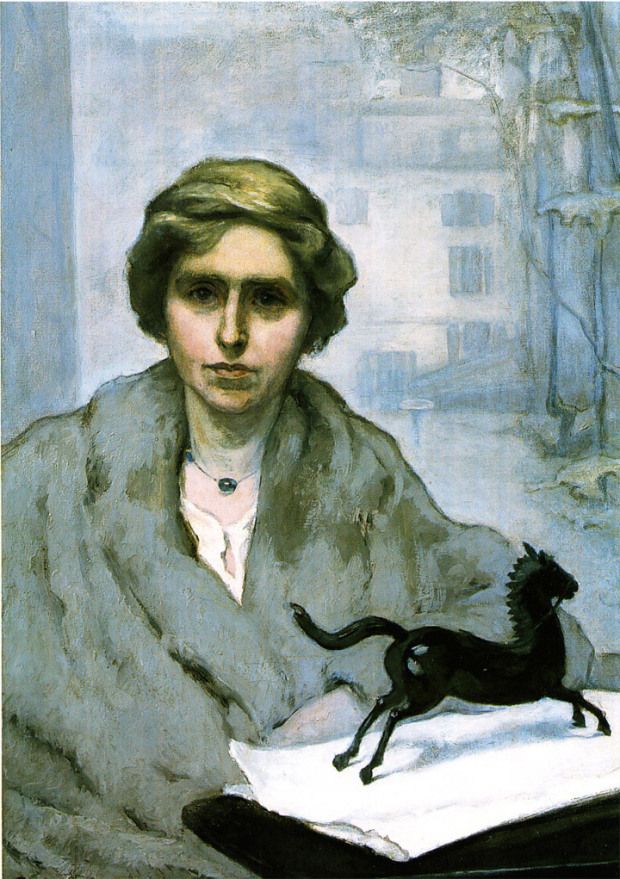

Natalie Clifford Barney by

Romaine Brooks, 1920

Natalie Clifford Barney and Renee Vivien

Lillian Cotton, (1901-1962). Boston, New York, Paris. Possibly Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks

Historical homosocial and homosexual communities of expatriate American and English women lived in Paris on the Left Bank of the Seine during the opening decades of the twentieth century. The place and time has captured the imaginations of feminist and queer historians, literary critics, art historians, and cultural theorists. These histories of women and their cultural productions are attractive because they demand a rethinking and rewriting of the canonical histories of masculine modernism. The geographical and spiritual locus for these groups were the literary and artistic salons of Natalie Barney and Gertrude Stein, as well as the bookshops and publishing houses owned by Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier. Congregating at these cultural landmarks, Janet Flanner, Colette, Renée Vivien, Djuna Barnes, Hilda Doolittle, Claude Cahun, Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Anaïs Nin, and many others invented new ways of living and representing themselves and each other. Martha Vicinus writes: The most striking aspect of the lesbian coteries of the 1910s and 1920s was their self-conscious effort to create a new sexual language for themselves that included not only words but also gestures, costume and behavior. Lillian Faderman notes that these Parisian communities “functioned as a support group for lesbians to permit them to create a self-image which literature and society denied them.”

Barney's salon was held at her home at 20 rue Jacob[1] in Paris's Left Bank for more than 60 years and brought together writers and artists from around the world, including many leading figures in French literature along with American and British Modernists of the Lost Generation. She worked to promote writing by women and formed a "Women's Academy" (L'Académie des Femmes) in response to the all-male French Academy while also giving support and inspiration to male writers from Remy de Gourmont to Truman Capote.[2]

She was openly lesbian and began publishing love poems to women under her own name as early as 1900, considering scandal as "the best way of getting rid of nuisances" (meaning heterosexual attention from young males).[3] She wrote in both French and English. In her writings she supported feminism and pacifism. She opposed monogamy and had many overlapping long and short-term relationships, including on-and-off romances with poet Renée Vivien and dancer Armen Ohanian and a 50-year relationship with painter Romaine Brooks. Her life and love affairs served as inspiration for many novels, ranging from the salacious French bestseller Idylle Saphique to The Well of Loneliness, the most famous lesbian novel of the twentieth century.[4]

Barney's earliest intimate relationship was with Eva Palmer-Sikelianos. In 1893 they became acquainted during summer vacations in Bar Harbor, Maine. Barney likened Palmer to a medieval virgin, an ode to her ankle length red hair, sea-green eyes and pale complexion.[24] The two remained close for a number of years. As young adults in Paris they shared an apartment at 4, rue Chalgrin. Later they each had their own place in Neuilly.[25] Barney frequently solicited Palmer's help in her romantic pursuits of other women, such as Pauline Tarn.[26] Palmer ultimately left Barney's side for Greece and eventually married Angelos Sikelianos. Their relationship did not survive this turn of events, Barney took a dim view of Angelos and heated letters were exchanged.[27] Later in their lives the friendship was repaired and both took a mature view on the roles they had played in each other's lives.[28]

In November 1899 Barney met the poet Pauline Tarn, better known by her pen name Renée Vivien. For Vivien it was love at first sight, while Barney became fascinated with Vivien after hearing her recite one of her poems,[29] which she described as "haunted by the desire for death."[30] Their romantic relationship was also a creative exchange that inspired both of them to write. Barney provided a feminist theoretical framework which Vivien explored in her poetry. They adapted the imagery of the Symbolist poets along with the conventions of courtly love to describe love between women, also finding examples of heroic women in history and myth.[31] Sappho was an especially important influence and they studied Greek so as to read the surviving fragments of her poetry in the original. Both wrote plays about her life.[32]

Vivien saw Barney as a muse and as Barney put it, "she had found new inspiration through me, almost without knowing me." Barney felt Vivien had cast her as a femme fatale and that she wanted "to lose herself... entirely in suffering" for the sake of her art.[33] Vivien also believed in fidelity, which Barney was unwilling to agree to. While Barney was visiting her family in Washington, D.C. in 1901, Vivien stopped answering her letters. Barney tried to get her back for years, at one point persuading a friend, operatic mezzo-soprano Emma Calvé, to sing under Vivien's window so she could throw a poem (wrapped around a bouquet of flowers) up to Vivien on her balcony. Both flowers and poem were intercepted and returned by a governess.[34]

In the spring of 1901, Olive Custance had travelled to Paris with her mother and the neighbour Freddie Manners-Sutton, the 21 years old son and heir of the Viscount of Canterbury. There he tried to court Custance's friend Natalie Clifford Barney, but she did not return his affections. He would remain a life-long bachelor. After Manners-Sutton went home, Custance had a brief fling with Barney, who shared her desire to transcend the rigid gender roles of society. Although she experimented with lesbian eroticism, Custance's real attraction was not to women but to men with feminine qualities. Before she met Lord Alfred Douglas, she had for years been infatuated with the poet John Gray.

In 1903 she and Renée Vivien went to Lesbos with the vague notion of setting up a lesbian colony there, but nothing came of it. If not exactly a colony, Barney’s salon was certainly the centre of a subculture. Claude Mauriac called her ‘the Pope of Lesbos’. Barney and Renée Vivien learned Greek in order to read the fragments in the original, visited Lesbos, where Vivien kept a villa, and sought out Pierre Louÿs, author of Les Chansons de Bilitis (Songs of Bilitis), billed as love poems written by one of Sappho’s lovers. Louÿs took a shine to Barney and gave her and Vivien autographed copies of his book.

In 1904 she wrote Je Me Souviens (I Remember), an intensely personal prose poem about their relationship which was presented as a single handwritten copy to Vivien in an attempt to win her back. They reconciled and traveled together to Lesbos, where they lived happily together for a short time and talked about starting a school of poetry for women like the one which Sappho, according to tradition, had founded on Lesbos some 2,500 years before. However, Vivien soon got a letter from her lover Baroness Hélène van Zuylen and went to Constantinople thinking she would break up with her in person. Vivien planned to meet Barney in Paris afterward but instead stayed with the Baroness and this time, the breakup was permanent.[34]

Vivien's health declined rapidly after this. According to Vivien's friend and neighbor Colette, she ate almost nothing and drank heavily, even rinsing her mouth with perfumed water to hide the smell.[35] Colette's account has led some to call Vivien an anorexic[36] but this diagnosis did not yet exist at the time. Vivien was also addicted to the sedative chloral hydrate. In 1908 she attempted suicide by overdosing on laudanum[37] and died the following year. In a memoir written fifty years later Barney said "She could not be saved. Her life was a long suicide. Everything turned to dust and ashes in her hands."[38]

Anna Wickham was forcibly committed to a mental hospital at the age of 30. Upon her release, she began a life-long quest for happiness, exhibited first and foremost through her poetry. Eventually leaving her husband and four sons to live in Paris's left bank in the early 1920s, she became the long-time lover of Barney. Despite her fame and achievement, Wickham's struggles with depression and anxiety would eventually lead to her untimely death in 1947.

In the 1920 Fola La Follette lists 20 Rue Jacob, as her address. In the summer of 1926, notwithstanding their usual misgivings, Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge allowed Natalie Barney to show them around some of the main lesbian clubs in Paris: the Select, the Regina and the Dingo. They made a special trip to Passy to lay flowers on Renée Vivien’s grave.

In 1927 Barney started an Académie des Femmes (Women's Academy) to honor women writers. This was a response to the influential French Academy which had been founded in the 17th century by Louis XIII and whose 40 "immortals" included no women at the time. Unlike the French Academy, her Women's Academy was not a formal organization, but rather a series of readings held as part of the regular Friday salons. Honorees included Colette, Gertrude Stein, Anna Wickham, Rachilde, Lucie Delarue-Mardrus, Mina Loy, Djuna Barnes and posthumously, Renée Vivien.[66]

Radclyffe Hall wrote The Well of Loneliness in 1928. As usual, it contained sketches of people she knew: Noël Coward as Jonathan Brockett, for instance, and Natalie Barney as Valérie Seymour.

Other visitors to the salon during the 1920s included French writers Jeanne Galzy,[67] André Gide, Anatole France, Max Jacob, Louis Aragon and Jean Cocteau along with English-language writers Ford Madox Ford, W. Somerset Maugham, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, Sherwood Anderson, Thornton Wilder, T. S. Eliot and William Carlos Williams and moreover, German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore (the first Nobel laureate from Asia), Romanian aesthetician and diplomat Matila Ghyka, journalist Janet Flanner (who set the New Yorker style), journalist, activist and publisher Nancy Cunard, publishers Caresse and Harry Crosby, publisher Blanche Knopf,[1] art collector and patron Peggy Guggenheim, Sylvia Beach (the bookstore owner who published James Joyce's Ulysses), painters Tamara de Lempicka and Marie Laurencin and dancer Isadora Duncan.[68]

Barney presided over her salon for almost sixty years. As well as important male literary figures from France – André Gide, Anatole France, Max Jacob, Louis Aragon, Jean Cocteau – her visitors included major literary figures from abroad: Ford Madox Ford, Sinclair Lewis, W. Somerset Maugham, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Carlos Williams, Thornton Wilder, Rainer Maria Rilke, Rabindranath Tagore … But the main focus of the salon was its women guests: Colette, Mata Hari, Sylvia Beach, Gluck, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Edna St Vincent Millay, Isadora Duncan, Nancy Cunard, Adrienne Monnier, Peggy Guggenheim, Janet Flanner, Greta Garbo, Françoise Sagan.

Barney’s centrality to Parisian literary life is further demonstrated by the fact that she was depicted – and depicted as a lesbian – in fictional works by Liane de Pougy, Renée Vivien (as Vally in Une Femme m’apparut), Ronald Firbank, Remy de Gourmont, Colette, Lucie Delarue-Mardrus and Radclyffe Hall (as Valerie Seymour in The Well of Loneliness). Djuna Barnes wrote a lively bagatelle called Ladies Almanack in 1928. Natalie Barney featured here as Dame Evangeline Musset; Romaine Brooks as Cynic Sal; Lily de Gramont as the Duchesse Clitoressa of Natescourt; Una Troubridge as Lady Buck-and-Balk; Radclyffe Hall as Tilly Tweed-in-blood; Mina Loy as Patience Scalpel; Mimì Franchetti as Senorita Fly-About; and Janet Flanner and Solita Solano as Nip and Tuck. The book was privately published by Robert McAlmon.

In 1949, two years after the death of Hélène van Zuylen, Barney restored the Renée Vivien Prize[39][40][41][42] with a financial grant[43] under the authority of the Société des gens de lettres and took on the chairmanship of the jury in 1950.[44][45][46]

Barney practiced, and advocated, non-monogamy. As early as 1901, in Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs, she argued in favor of multiple relationships and against jealousy;[85] in Éparpillements she wrote "One is unfaithful to those one loves in order that their charm does not become mere habit."[86] While she could be jealous herself, she actively encouraged at least some of her lovers to be non-monogamous as well.[87]

Due in part to Jean Chalon's early biography of her, published in English as Portrait of a Seductress, she had become more widely known for her many relationships than for her writing or her salon.[88] She once wrote out a list, divided into three categories: liaisons, demi-liaisons, and adventures. Colette was a demi-liaison, while the artist and furniture designer Eyre de Lanux, with whom she had an off-and-on affair for several years, was listed as an adventure. Among the liaisons—the relationships that she considered most important—were Olive Custance, Renée Vivien, Élisabeth de Gramont, Romaine Brooks, and Dolly Wilde.[89] Of these, the three longest relationships were with de Gramont, Brooks, and Wilde; from 1927, she was involved with all three of them simultaneously, a situation that ended only with Wilde's death. Her shorter affairs, such as those with Colette and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus, often evolved into lifelong friendships.

Élisabeth de Gramont, the Duchess of Clermont-Tonnerre, was a writer best known for her popular memoirs.[90] A descendant of Henry IV of France, she had grown up among the aristocracy; when she was a child, according to Janet Flanner, "peasants on her farm... begged her not to clean her shoes before entering their houses".[91] She looked back on this lost world of wealth and privilege with little regret, and became known as the "red duchess" for her support of socialism. She was married and had two daughters in 1910, when she met Barney; her husband is said to have been violent and tyrannical.[92] They eventually separated, and in 1918 she and Barney wrote up a marriage contract stating: "No one union shall be so strong as this union, nor another joining so tender—nor relationship so lasting."[93]

De Gramont accepted Barney's nonmonogamy—perhaps reluctantly at first—and went out of her way to be gracious to her other lovers,[94] always including Romaine Brooks when she invited Barney to vacation in the country.[95] The relationship continued until de Gramont's death in 1954.

Barney's longest relationship was with the American painter Romaine Brooks, whom she met around 1914. Brooks specialized in portraiture and was noted for her somber palette of gray, black, and white. During the 1920s she painted portraits of several members of Barney's social circle, including de Gramont and Barney herself.

Brooks tolerated Barney's casual affairs well enough to tease her about them, and had a few of her own over the years, but could become jealous when a new love became serious. Usually she simply left town, but at one point she gave Barney an ultimatum to choose between her and Dolly Wilde—relenting once Barney had given in.[96] At the same time, while Brooks was devoted to Barney, she did not want to live with her as a full-time couple; she disliked Paris, disdained Barney's friends, hated the constant socializing on which Barney thrived, and felt that she was fully herself only when alone.[97] To accommodate Brooks's need for solitude they built a summer home consisting of two separate wings joined by a dining room, which they called Villa Trait d'Union, the hyphenated villa. Brooks also spent much of the year in Italy or travelling elsewhere in Europe, away from Barney.[98] They remained devoted to one another for over fifty years.

Dolly Wilde was the niece of Oscar Wilde (whom Natalie Barney had met as a little girl[99]) and the last of her family to bear the Wilde name. She was renowned for her epigrammatic wit but, unlike her famous uncle, never managed to apply her gifts to any publishable writing; her letters are her only legacy. She did some work as a translator and was often supported by others, including Barney, whom she met in 1927.[100]

Like Vivien, Wilde seemed bent on self-destruction. She drank heavily, was addicted to heroin, and attempted suicide several times. Barney financed Drug detoxifications, which were never effective; she emerged from one nursing-home stay with a new dependency on the sleeping draught paraldehyde, then available over-the-counter.[101]

In 1939 she was diagnosed with breast cancer and refused surgery, seeking alternative treatments.[102] The following year, World War II separated her from Barney; she fled Paris for England while Barney went to Italy with Brooks.[103] She died in 1941 from causes that have never been fully explained, possibly a paraldehyde overdose.[104]

Villa Trait d'Union was destroyed by bombing during WWII. After the war, Brooks declined to live with Barney in Paris; she remained in Italy, and they visited each other frequently.[110] Their relationship remained monogamous until the mid-1950s, when Barney met her last new love, Janine Lahovary, the wife of a retired Romanian ambassador. Lahovary made a point of winning Romaine Brooks's friendship, Barney reassured Brooks that their relationship still came first, and the triangle appeared to be stable.[111]

The salon resumed in 1949 and continued to attract young writers for whom it was as much a piece of history as a place where literary reputations were made. Truman Capote was an intermittent guest for almost ten years; he described the decor as "totally turn-of-the-century" and remembered that Barney introduced him to the models for several characters in Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time.[112] Alice B. Toklas became a regular after Gertrude Stein's death in 1946. Fridays in the 1960s honored Mary McCarthy and Marguerite Yourcenar, who in 1980—eight years after Barney's death—became the first female member of the French Academy.[113]

Barney did not return to writing epigrams, but did publish two volumes of memoirs about other writers she had known, Souvenirs Indiscrets (Indiscreet Memories, 1960) and Traits et Portraits (Traits and Portraits, 1963). She also worked to find a publisher for Brooks's memoirs and to place her paintings in galleries.[114]

In the late 1960s Brooks became increasingly reclusive and paranoid; she sank into a depression and refused to see the doctors Barney sent. Bitter at Lahovary's presence during their last years, which she had hoped they would spend exclusively together, she finally broke off contact with Barney. Barney continued to write to her, but received no replies. Brooks died in December 1970, and Barney on February 2, 1972 of heart failure.[115] She is buried at Passy Cemetery, Paris, Île-de-France, France.[116]

Rt. Rev. Paul Moore (1919-2003), Honor Moore (born 1945), Richard Nathan Olney (1927-1999) and Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972), all descend from the same Mayflower Pilgrim, Ricchard Warren.

Tony

Scupham-Bilton - Mayflower 400 Queer Bloodlines

My published books: