Partner Kinmont Hoitsma

Queer Places:

St Cyprian's School, 67 Summerdown Rd, Eastbourne BN20 8DQ, Regno Unito

Harrow School, 5 High St, Harrow HA1 3HP, Regno Unito

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

8 Pelham Pl, South Kensington, London SW7 2NH, UK

139 Kensington High St, London W8 6SU, UK

47 Bridge St, Cambridge CB2, UK

Reddish House Cottages, South St, Broad Chalke, Salisbury SP5 5DL, Regno Unito

Ashcombe House, Tollard Royal, Salisbury SP5 5QG, Regno Unito

Sir

Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton CBE (14 January 1904 – 18 January 1980) was an

English fashion, portrait and war photographer, diarist, painter, interior

designer and an Oscar–winning stage and costume designer for films and the

theatre. Interior decorator, socialite and friend

David Herbert described Beaton in the

following manner: "Tall, thin and willowy, he had the most remarkable eyes:

violet and piercing, set flat against his face and as far apart as a goat's...

he "walked delicately," unlike most Englishmen he used his hands expressively

when talking." His best friend

Stephen Tennant was more profound in his description, claiming Beaton

always struggled to redesign himself into a better version, less cruel through

his wit. Beaton's cruelty was noted by many, and he recalled how

Jean Cocteau christened him "Malice

in Wonderland" and chided him for, according to him, "spending my life in

unreality made up of fun, too much fun and my interests are limited to the

joys of certain superficial forms of beauty, to sensual delights only to a

certain blunt degree, and with too many people, to many light quick sketches,

quick fire articles and photographs galore. The crowded weeks gave place to

others and I am under the delusion that I am "living" so much more vitally

than I should have if I had "gone my own way.""

Sir

Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton CBE (14 January 1904 – 18 January 1980) was an

English fashion, portrait and war photographer, diarist, painter, interior

designer and an Oscar–winning stage and costume designer for films and the

theatre. Interior decorator, socialite and friend

David Herbert described Beaton in the

following manner: "Tall, thin and willowy, he had the most remarkable eyes:

violet and piercing, set flat against his face and as far apart as a goat's...

he "walked delicately," unlike most Englishmen he used his hands expressively

when talking." His best friend

Stephen Tennant was more profound in his description, claiming Beaton

always struggled to redesign himself into a better version, less cruel through

his wit. Beaton's cruelty was noted by many, and he recalled how

Jean Cocteau christened him "Malice

in Wonderland" and chided him for, according to him, "spending my life in

unreality made up of fun, too much fun and my interests are limited to the

joys of certain superficial forms of beauty, to sensual delights only to a

certain blunt degree, and with too many people, to many light quick sketches,

quick fire articles and photographs galore. The crowded weeks gave place to

others and I am under the delusion that I am "living" so much more vitally

than I should have if I had "gone my own way.""

The work of Broadway's gay and lesbian artistic community went on display in 2007 when the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation Gallery presents "StageStruck: The Magic of Theatre Design." The exhibit was conceived to highlight the achievements of gay and lesbian designers who work in conjunction with fellow gay and lesbian playwrights, directors, choreographers and composers. Original sketches, props, set pieces and models — some from private collections — represent the work of over 60 designers, including Cecil Beaton.

One of the most unusual aspects of the Stettheimers’ salon was the large number of their gay, bisexual, and lesbian friends and acquaintances, who were comfortable being their authentic selves among their straight friends. Several of the sisters’ closest friends, including Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, Henry McBride, Virgil Thomson, and Baron Adolph de Meyer (married to a lesbian, Olga Carracciolo) were homosexual; Carl Van Vechten, Cecil Beaton, and Georgia O’Keeffe were bisexual; Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks were lesbians; and Alfred Stieglitz, Marcel Duchamp, Gaston Lachaise, Marie Sterner, and Leo Stein were heterosexual. This open, natural mix of friends with different sexual preferences continued when Stettheimer held salons in her studio in the Beaux Arts building in midtown Manhattan, although later in life she also had parties where most of the guests were strong feminist women.

Beaton was born on 14 January 1904 in Hampstead, the son of Ernest Walter Hardy Beaton (1867–1936), a prosperous timber merchant, and his wife, Esther "Etty" Sisson (1872–1962). His grandfather, Walter Hardy Beaton (1841–1904), had founded the family business of "Beaton Brothers Timber Merchants and Agents", and his father followed into the business. Ernest Beaton was an amateur actor and met his wife, Cecil's mother Esther ("Etty"), when playing the lead in a play. She was the daughter of a Cumbrian blacksmith named Joseph Sisson and had come to London to visit her married sister.[2]

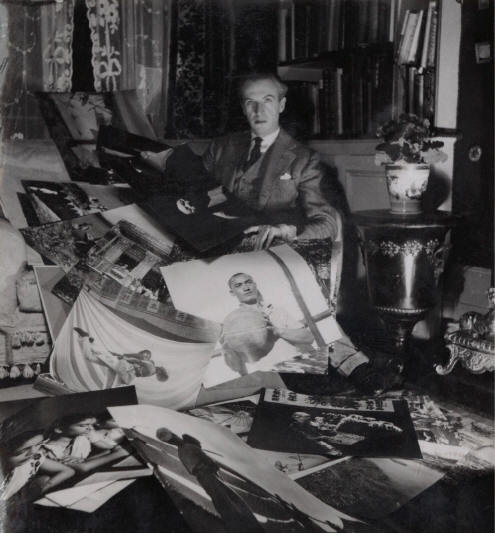

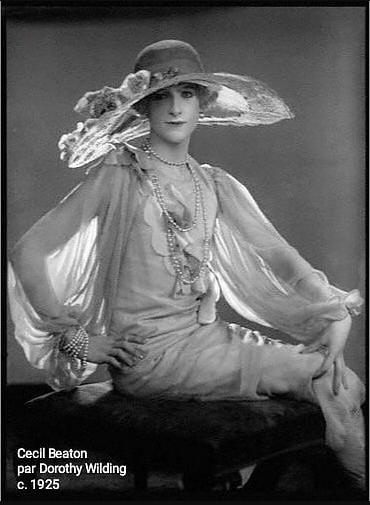

Cecil Beaton

Francis Goodman (1913–1989)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Cecil Beaton

by Francis Goodman

bromide contact print, 28 November 1945

2 1/8 in. x 2 in. (55 mm x 51 mm) image size

Purchased, 1988

Photographs Collection

NPG Ax39603

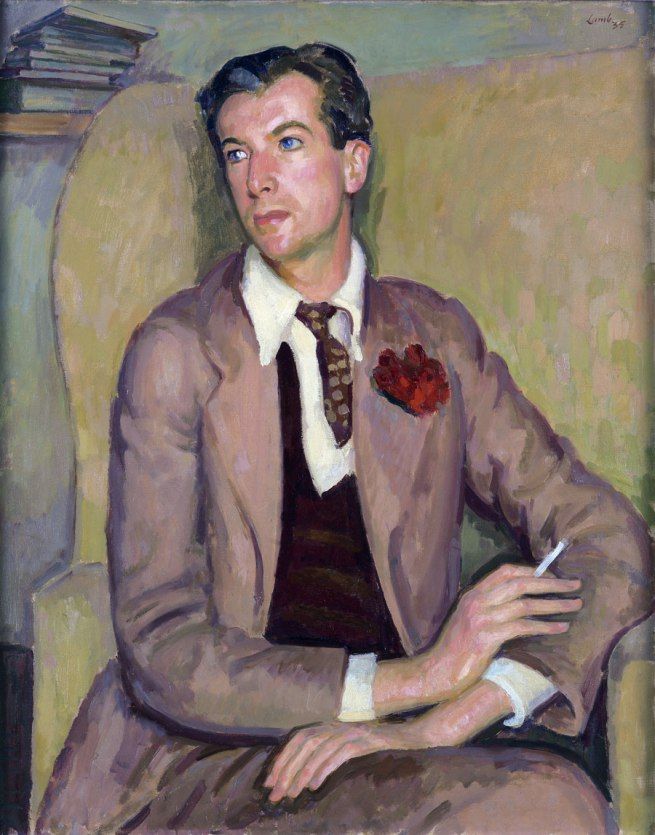

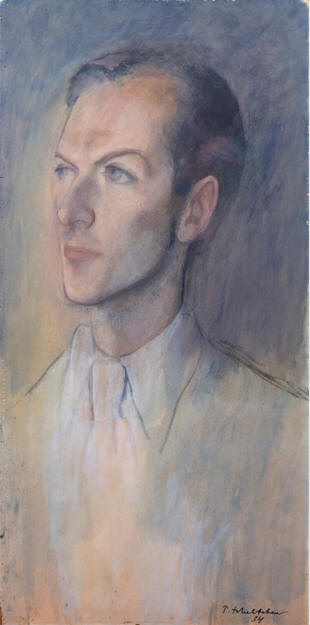

Cecil Beaton by Henry Lamb

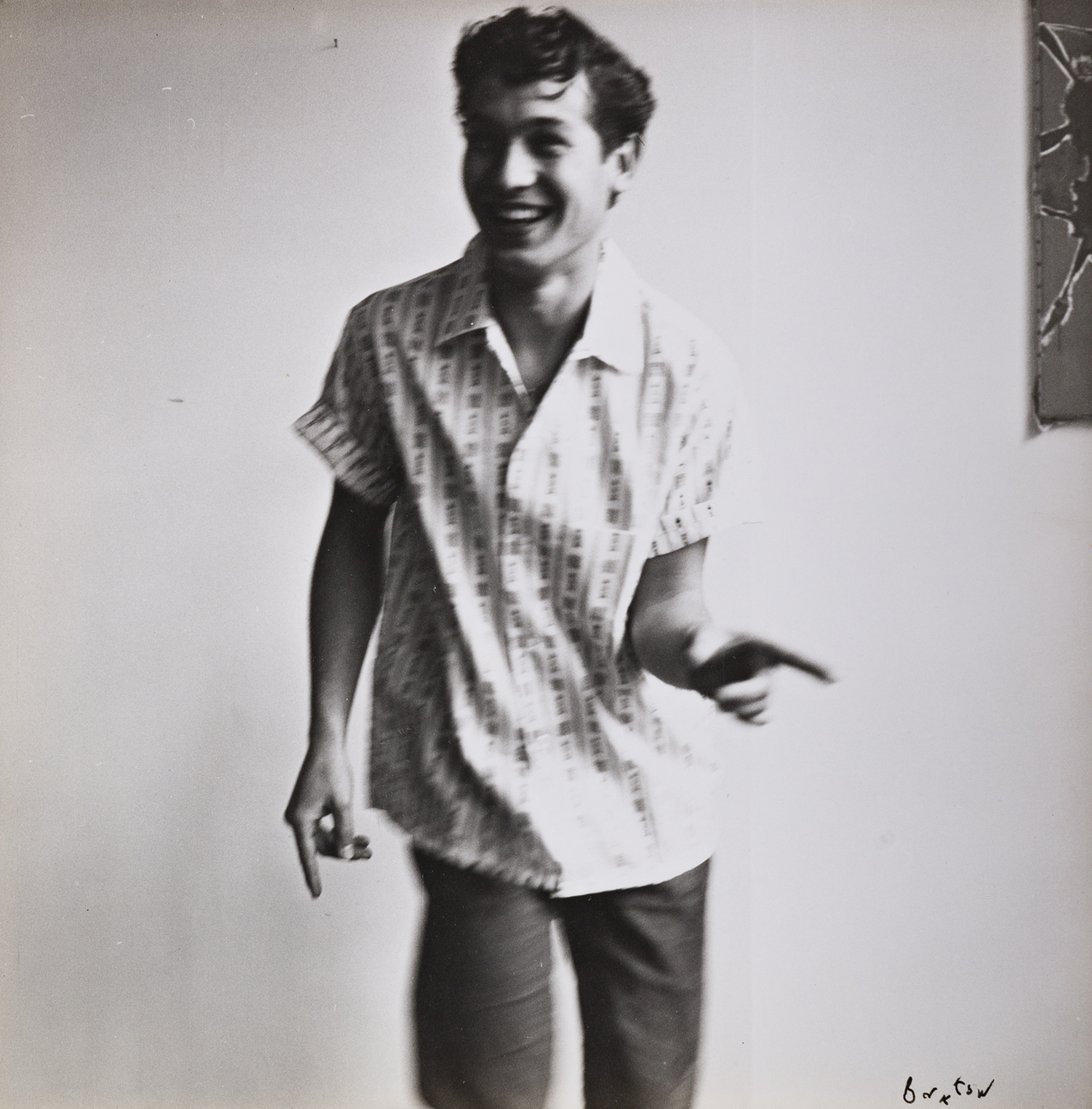

Cecil Beaton

by Lewis Morley

bromide print, 1960

15 1/8 in. x 11 3/8 in. (384 mm x 290 mm)

Given by the photographer, Lewis Morley, 1992

Primary Collection

NPG P512(2)

Cecil Beaton

by Paul Tanqueray

resin contact print from original negative, 1937

Given by Paul Tanqueray, 1980

Photographs Collection

NPG x44847a

Alfred Lunt; Lynn Fontanne; Cecil Beaton; Noël Coward

by Paul Tanqueray

vintage bromide print, 1952

8 in. x 9 7/8 in. (204 mm x 252 mm)

Accepted in lieu of tax by H.M. Government and allocated to the Gallery, 1991

Photographs Collection

NPG x40493

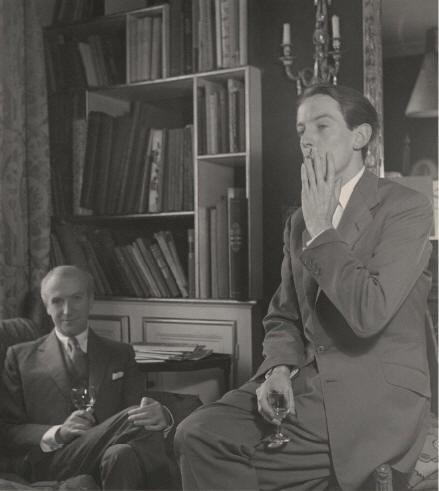

Cecil Beaton; Kenneth Peacock Tynan

by Paul Tanqueray

vintage bromide print, 1953

8 3/4 in. x 7 3/4 in. (221 mm x 198 mm)

Accepted in lieu of tax by H.M. Government and allocated to the Gallery, 1991

Photographs Collection

NPG x40492

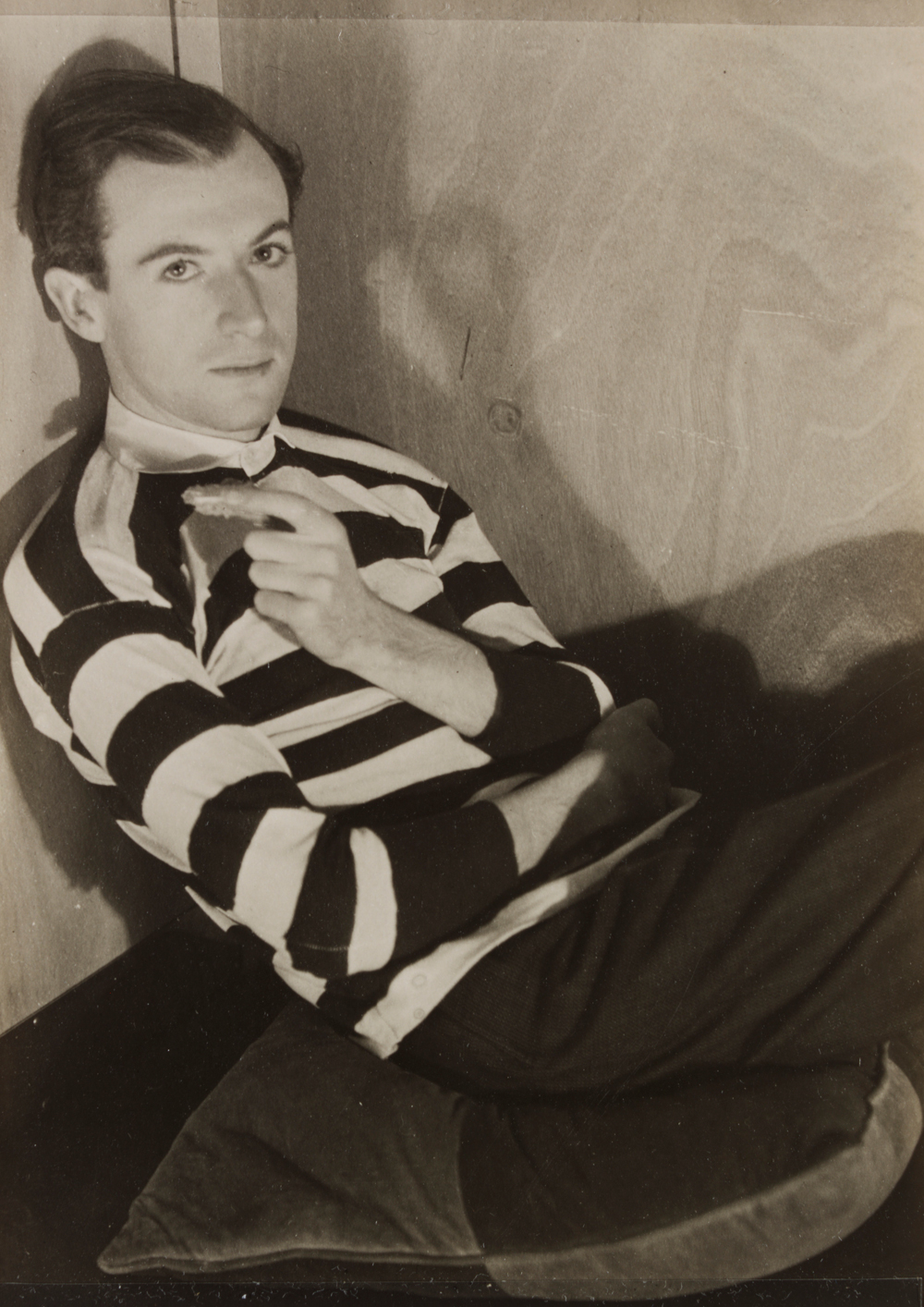

Cecil Beaton, 1934, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Cecil Beaton, self-portrait as aesthete, at home in Wiltshire: a study in

calculated informality

Nancy Beaton

by Paul Tanqueray

vintage bromide print, 1928

9 5/8 in. x 7 1/2 in. (243 mm x 192 mm)

Given by Paul Tanqueray, 1974

Photographs Collection

NPG x7252

Baba Beaton

by Paul Tanqueray

bromide print, 1932

9 1/2 in. x 7 1/2 in. (242 mm x 190 mm)

Given by Paul Tanqueray, 1974

Photographs Collection

NPG x7251

CECIL BEATON (1904-1980) & HERBERT LIST (1903-1975)

A trio of photographs of Andrea Tagliabue.

Silver prints, the images measuring 279.4x228.6 mm.; 11x9 inches and 241.3 mm.; 9 1/2 inches square, the Beatons with his signature, in ink, on recto and his hand stamp on verso; the List with his signature, title, date, and various notations, in ink, on verso. Circa 1960s.

Andrea Tagliabue met the bohemian artist and author Charles Henry Ford in the 1960s while Tagliabue was working as a film actor in Italy. The two quickly formed a bond and lived together in Paris and eventually New York. Through Ford, Tagliabue was introduced to the wider LGBQT+ community that existed in Lower Manhattan during the 60s and 70s.

Sylvia Townsend Warner, 1930

Stephen Tennant, as Prince Charming, 1927

Madge Garland, 1927

Isabel Jeans

by Cecil Beaton

bromide print on white card mount, 1944

9 1/2 in. x 7 3/4 in. (241 mm x 195 mm)

Given by Cecil Beaton, 1968

Photographs Collection

NPG x14118

St Cyprian's Lodge, Eastbourne

St John’s College, Cambridge

Ernest and Etty Beaton had four children – Cecil; two daughters, Nancy Elizabeth Louise Hardy Beaton (1909–99, who married Sir Hugh Smiley) and Barbara Jessica Hardy Beaton (1912–73, known as Baba, who married Alec Hambro); and son Reginald Ernest Hardy Beaton (1905–33).

Cecil Beaton was educated at Heath Mount School (where he was bullied by Evelyn Waugh) and St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne, where his artistic talent was quickly recognised. Both Cyril Connolly and Henry Longhurst report in their autobiographies being overwhelmed by the beauty of Beaton's singing at the St Cyprian's school concerts.[3][4] When Beaton was growing up his nanny had a Kodak 3A Camera, a popular model which was renowned for being an ideal piece of equipment to learn on. Beaton's nanny began teaching him the basics of photography and developing film. He would often get his sisters and mother to sit for him. When he was sufficiently proficient, he would send the photos off to London society magazines, often writing under a pen name and ‘recommending’ the work of Beaton.[5]

Cecil Beaton attended Harrow School from 1918. On 25 January 1926, after he had come down from Cambridge without a degree, Beaton wrote that: I wondered why I had painted my face [at Harrow]. I always used to powder and put red stuff on my lips. It’s so idiotic to think that people don’t notice it … Now I squirm to see a man powdered. I must have been rather awful at Harrow and I used to think I was so marvelous, so witty and bright and subtle and interesting.

Beaton attended Harrow School, and then, despite having little or no interest in academia, moved on to St John's College, Cambridge, and studied history, art and architecture. Beaton continued his photography, and through his university contacts managed to get a portrait depicting the Duchess of Malfi published in Vogue. It was actually George "Dadie" Rylands – "a slightly out-of-focus snapshot of him as Webster's Duchess of Malfi standing in the sub-aqueous light outside the men's lavatory of the ADC Theatre at Cambridge."[6] Beaton left Cambridge without a degree in 1925.

After a short time in the family timber business, he worked with a cement merchant in Holborn. This resulted in 'an orgy of photography at weekends' so he decided to strike out on his own.[7] Under the patronage of Osbert Sitwell he put on his first exhibition in the Cooling Gallery, London. It caused quite a stir.

Believing that he would meet with greater success on the other side of the Atlantic, he left for New York and slowly built up a reputation there. By the time he left, he had "a contract with Condé Nast Publications to take photographs exclusively for them for several thousand pounds a year for several years to come."[8]

In 1926 Cecil Beaton was invited to a party at British Vogue editors Madge Garland and Dorothy Todd's homse where he met socialites like actor Tom Douglas, Elizabeth Ponsonby and Cynthia Noble (Lady Gladwyn). At the party Freddie Ashton performed campy, "shy-making imitations of various ballet dancers and Queen Alexandra, the sort of thing one is ashamed of and only does in one's bedroom in front of large mirrors when one is rather excited and worked up."

In the summer of 1927 Noël Coward, whom Beaton looked up to, satirized the young man and the Bright Young Things in his song "I've been to a marvellous party," in which he sang: "Dear Cecil arrived wearing armour, Some shells and a black feather boa." Upon meeting him for the first time in April 1930, when the playwright was at sea, travelling with Venetia Montagu from New York to London, he assailed Beaton for the "malicious" article he had written on one of his recent plays. Coward attacked asserting: ""You must expect to be attacked if you write such horrible things." But there was so much truth in what they had to say that I could not deny it. As for Coward, the truth is that I've wanted to meet him for many years. I adore everything about his work: his homesick, sadly melodious tunes, his revues, his witty plays, his astringent acting. Yet both came to the same conclusion: I was flobby, flabby and affected." On a second encounter, Beaton was given a lesson on corporeal and sartorial management. Mocking his effeminate walk and voice, Coward reproached him: "It is important not to let the public have a loophole to lampoon you." Beaton remarked how Coward surveyed himself, looking at his "facade" carefully, the very same facade used to perform his masculinity, off stage. Coward once again chastised Beaton, stating: "You should appraise yourself. Your sleeves are too tight, your voice is too high, and too precise. You mustn't do it. It closes so many doors. It's hard, I know. One would like to indulge one's own taste. I myself dearly love a good match, yet I know it is overdoing it to wear tie, socks and handerchief of the same colour. I take ruthless stock of myself in the mirror before going out. A polo jumper or unfortunate tie exposes one to danger."

Virginia Woolf, long celebrated for her queer sense and sensibility, declined to sit for Cecil Beaton on the false pretence she was staying on in Sussex where she had already been for some time. In reality, as she later confessed to Vita Sackville-West, she had refused him precisely because of his "style and manner" and claimed him simply to be "a mere catamite."

Beaton designed book jackets, and costumes for charity matinees, learning the craft of photography at the studio of Paul Tanqueray, until Vogue took him on regularly in 1927.[13] He set up his own studio, and one of his earliest clients and, later, best friends was Stephen Tennant. Beaton's photographs of Tennant and his circle are considered some of the best representations of the Bright Young People of the twenties and thirties.

From 1930 to 1945, Beaton leased Ashcombe House in Wiltshire, where he entertained many notable figures. Cecil Beaton attended a costume party given by Elsa Maxwell at the Waldorf in New York on May 1, 1934, at which he elected not to dress as a fantastical character, but in drag as the celebrated interior decorator Lady Mendl (Elsie de Wolfe). Cecil Beaton’s country house Ashcombe barely existed in the real world at all. His bedroom was decorated with circus scenes, including a fat woman by Rex Whistler, a tumbler by Christopher Sykes, a naked Negro by Oliver Messel and, by Lord Berners, a Columbine with performing dogs. (All had been guests together on the same rainy weekend.) ‘Meanwhile,’ as Beaton later put it, ‘unhampered by a social conscience, we gave parties.’ Indeed, the eye grew so used to seeing people in fancy dress that, ‘when Mr. H.G. Wells was brought over one Sunday wearing a Homburg hat and pin-stripe suit, one felt he was the man from Mars’. There would be parodies of school sports days, with the prizes presented by John Sutro or Oliver Messel in drag. So full were the days with entertainment that Beaton was once shocked to find Tom Mitford reading a novel. Christian Bérard thought Ashcombe ‘pure Lewis Carroll’.

In 1930, Beaton began a lifelong obsession with Peter Watson, though the two never became lovers (Watson at the time was having a flirt with common friend Oliver Messel). Truman Capote once wrote to Beaton's biographer Hugo Vickers exposing the symbolism of Beaton's decorating choices: "In Cecil's house there was a book on the desk, a XIX century novel and a book mark in the place where one of the characters says: "I love you, Mr Watson." One chapter from Vickers' authorized biography of Beaton is titled "I Love You, Mr. Watson".

Beaton was a photographer for the British edition of Vogue in 1931 when George Hoyningen-Huene, photographer for the French Vogue travelled to England with his new friend Horst. Horst himself would begin to work for French Vogue in November of that year. The exchange and cross pollination of ideas between this collegial circle of artists across the Channel and the Atlantic gave rise to the look of style and sophistication for which the 1930s are known.[14]

Beaton is known for his fashion photographs and society portraits. He worked as a staff photographer for Vanity Fair and Vogue in addition to photographing celebrities in Hollywood. In 1938, he inserted some tiny-but-still-legible anti-Semitic phrases (including the word 'kike') into American Vogue at the side of an illustration about New York society. The issue was recalled and reprinted, and Beaton was fired.[15]

Beaton returned to England, where the Queen recommended him to the Ministry of Information (MoI). He became a leading war photographer, best known for his images of the damage done by the German Blitz. His style sharpened and his range broadened, Beaton's career was restored by the war.[16]

Beaton often photographed the Royal Family for official publication.[17] Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother was his favourite royal sitter, and he once pocketed her scented hankie as a keepsake from a highly successful shoot. Beaton took the famous wedding pictures of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor (wearing an haute couture ensemble by the noted American fashion designer Mainbocher).

During the Second World War, Beaton was first posted to the Ministry of Information and given the task of recording images from the home front. During this assignment he captured one of the most enduring images of British suffering during the war, that of 3-year-old Blitz victim Eileen Dunne recovering in hospital, clutching her beloved teddy bear. When the image was published, America had not yet officially joined the war, but images such as Beaton’s helped push the Americans to put pressure on their government to help Britain in its hour of need.[5]

After the war, Beaton tackled the Broadway stage, designing sets, costumes, and lighting for a 1946 revival of Lady Windermere's Fan, in which he also acted.

In 1947 Waldemar Hansen, later Peter Watson's lover, got a job with Cecil Beaton, serving as his secretary, although all-around amanuensis would be a more precise description. They got along well, considering that Hansen approved of little that Beaton wrote or designed or photographed. "Perennial chi-chi," Hansen would say, "but of course the world would be a dull place without a luttle chi-chi." In the end he liked Cecil's character.

In 1947, he bought Reddish House, set in 2.5 acres of gardens, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) to the east in Broad Chalke. Here he transformed the interior, adding rooms on the eastern side, extending the parlour southwards, and introducing many new fittings. Greta Garbo was a visitor.[9] He remained at the house until his death in 1980 and is buried in the churchyard.[10][11][12]

Passionate about privacy, Sydney Guilaroff granted a rare interview to the writer John Kobal in the 1950s but refused to be tape-recorded. Unwilling to reveal much about himself, Sydney did prove to be a "fascinating gossip" about other people, calling Cecil Beaton "a swishy little boy" and Oliver Messel "small-minded and nasty."

In 1956 John Bernard Myers was a guest for a few days at Reddish House. Cecil Beaton's mother, although of great age, was still vigorous enough to do a little gardening and to enjoy the pugs that scampered underfoot. Beaton had a glass room with a small pool in the center of a wide variety of potted plants on shelves; there they would have tea. Mrs Beaton was particularly proud of the tuberoses. Tall, daughty, very proper, the old lady, when Beaton told her he was considering marriage to Greta Garbo, looked at him sternly and asked, "Pray, who may that be?", and became quite frigid when he explained she was an actress.

His costumes for Lerner and Loewe's My Fair Lady (1956) were highly praised. This led to two Lerner and Loewe film musicals, Gigi (1958) and My Fair Lady (1964), each of which earned Beaton the Academy Award for Best Costume Design. He also designed the period costumes for the 1970 film On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.

Additional Broadway credits include The Grass Harp (1952), The Chalk Garden (1955), Saratoga (1959), Tenderloin (1960), and Coco (1969). He is the recipient of four Tony Awards.

He designed the sets and costumes for a production of Puccini’s last opera Turandot, first used at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and then at Covent Garden.

Beaton had a major influence on and relationship with Angus McBean and David Bailey. McBean was a well-known portrait photographer of his era. Later in his career, his work is influenced by Beaton. Bailey was influenced by Beaton when they met while working for British Vogue in the early 1960s. Bailey's use of square format (6x6) images is similar to Beaton's own working patterns.

In 1972 Cecil Beaton designed for the ballet Illuminations. He asked to John Bernard Myers to make suggestions and he suggested Beaton look at the work of Paul Klee for an image to suggest a dour sky and crazy-looking church suitable for the painted backdrop. Just before the opening, at a dress rehearsal, Beaton and the choreographer Frederick Ashton got into a screaming squarrel about Karinska's dressmaking. Beaton was devoted to Karinska. Somebody asked Lincoln Kirstein what the ruckus was downstairs, and Lincoln replied, "Oh, Cecil and Freddie are once again at needlepoints..." The two of them were the best of friends, but temperamental when it came to production time.

Cecil Beaton was a published and well-known diarist. In his lifetime, six volumes of diaries were published, spanning the years 1922–1974. Recently some unexpurgated material has been published. "In the published diaries, opinions are softened, celebrated figures are hailed as wonders and triumphs, whereas in the originals, Cecil can be as venomous as anyone I have ever read or heard in the most shocking of conversation" wrote their editor, Hugo Vickers.[19]

The last public interview given by Sir Cecil Beaton was in January 1980 for an edition of the BBC's Desert Island Discs. The interviewer was Desert Island Discs' creator Roy Plomley. The recording was broadcast on Friday 1 February 1980 following the Beaton family's permission, and is now available as a podcast from the BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Disc archive 1976 - 1980. Owing to Beaton's frailty, the interview was recorded at Beaton's 17th Century home of Reddish House in Broad Chalke in Wiltshire (near Salisbury).

Beaton, though frail, recalled events in his life, particularly from the 1930s and 1940s (the Blitz). Among the recollections were his associations with stars of Hollywood and British Royalty notably The Duke and Duchess of Windsor (whose official wedding photographs Beaton took on 3 June 1937 at relatively short notice); and official portraits of Queen Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother) and Her Majesty The Queen on her coronation day on 2 June 1953. The interview also alluded to a lifelong passion for performing arts and in particular ballet and operetta. The Beaton programme is considered to be almost the final words on an era of 'Bright Young Things' whose sunset had taken place by the time of the abdication of Edward VIII. Beaton commented specifically on Wallis Simpson (later titled The Duchess of Windsor after her marriage to the former king Edward VIII) giving perhaps an insight as to her character that has not at any time been freely expressed (The Duchess of Windsor at the time of the original Beaton interview and broadcast was still alive and living in relative solitude just outside Paris - it quite possible though unconfirmed, that the Duchess may have indeed heard this edition of Desert Island Discs).

In closing, Roy Plomley asked Beaton for the one record that he would retain on the Desert Island should the others get washed away on the tide. The immediate reply was Beethoven's Symphony No 1. Beaton's chosen book was a compendium of photographs he had taken down the years of "...people known and unknown; people known but now forgotten."

Beaton had relationships with various men: his last lover was former Olympic fencer and teacher Kinmont Hoitsma.[20] He also had relationships with women, including the actresses Greta Garbo and Coral Browne, the dancer Adele Astaire, the Greek socialite Madame Jean Ralli (Lilia) (died 1977),[21] and the British socialite Doris Castlerosse (1900–42).

He was knighted in the 1972 New Year Honours.[22]

Two years later he suffered a stroke that would leave him permanently paralysed on the right side of his body. Although he learnt to write and draw with his left hand, and had cameras adapted, Beaton became frustrated by the limitations the stroke had put upon his work. As a result of his stroke, Beaton became anxious about financial security for his old age and, in 1976, entered into negotiations with Philippe Garner, expert-in-charge of photographs at Sotheby's. On behalf of the auction house, Garner acquired Beaton's archive—excluding all portraits of the Royal Family, and the five decades of prints held by Vogue in London, Paris and New York. Garner, who had almost singlehandedly invented the photographic auction, oversaw the archive's preservation and partial dispersal, so that Beaton's only tangible assets, and what he considered his life's work, would ensure him an annual income. The first of five auctions was held in 1977, the last in 1980.

By the end of the 1970s, Beaton's health had faded. He died on 18 January 1980, at Reddish House, his home in Broad Chalke, Wiltshire, 4 days after his 76th birthday.[5]

My published books: