Partner Sybil Cookson, Nesta Obermer, Edith Shackleton Heald

Queer Places:

32 Compayne Gardens, London NW6 3DN, UK

73 Avenue Rd, London N14 4DD, UK

48 Tite Street, London SW3

Bolton House, Windmill Hill, London NW3 6SJ, UK

Chantry House, 51 Church St, Steyning BN44 3YB, UK

Hannah

Gluckstein, known as Gluck (13 August 1895 – 10 January 1978) was an

unconventional British painter. After relationships with the journalist

Sybil Cookson and floral designer

Constance Spry, she fell

passionately in love with Nesta

Obermer in the mid-1930s. Although the relationship between the two was

extremely fraught, Obermer, who never left her husband, appears to have been

the love of Gluck's life. By the mid-1940s Gluck became involved with

Edith Shackleton Heald.

Hannah

Gluckstein, known as Gluck (13 August 1895 – 10 January 1978) was an

unconventional British painter. After relationships with the journalist

Sybil Cookson and floral designer

Constance Spry, she fell

passionately in love with Nesta

Obermer in the mid-1930s. Although the relationship between the two was

extremely fraught, Obermer, who never left her husband, appears to have been

the love of Gluck's life. By the mid-1940s Gluck became involved with

Edith Shackleton Heald.

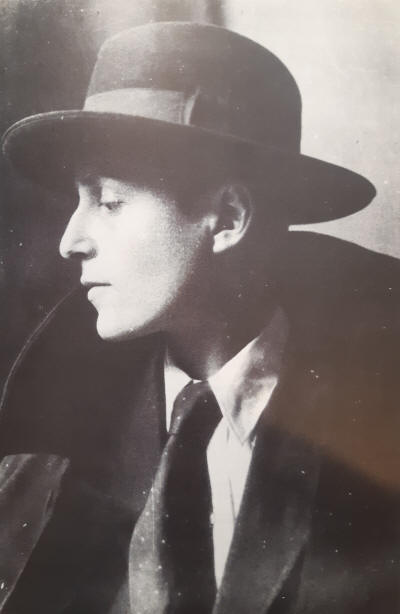

A number of novels were published in the years after the First World War, which tackled the theme of lesbianism and brought the issue to a wider audience. The most influential of these was Radclyffe Hall's novel The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928, whose trial and subsequent banning for obscenity was the subject of widespread press attention. The decade also saw the formation of explicitly lesbian communities such as the expatriate lesbian community of the Parisian left bank, while individual self-identified lesbians, including Radclyffe Hall and the artist Gluck, employed clothing and mannerism to express themselves as lesbian.

Gluck was born into a wealthy Jewish family in London. Gluck's father was Joseph Gluckstein, whose brothers Isidore and Montague had founded J. Lyons and Co., a British coffee house and catering empire. Gluck's American-born mother, Francesca Halle, was an opera singer. Her brother, Sir Louis Gluckstein, was a Conservative politician.

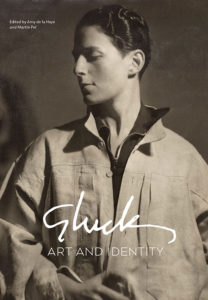

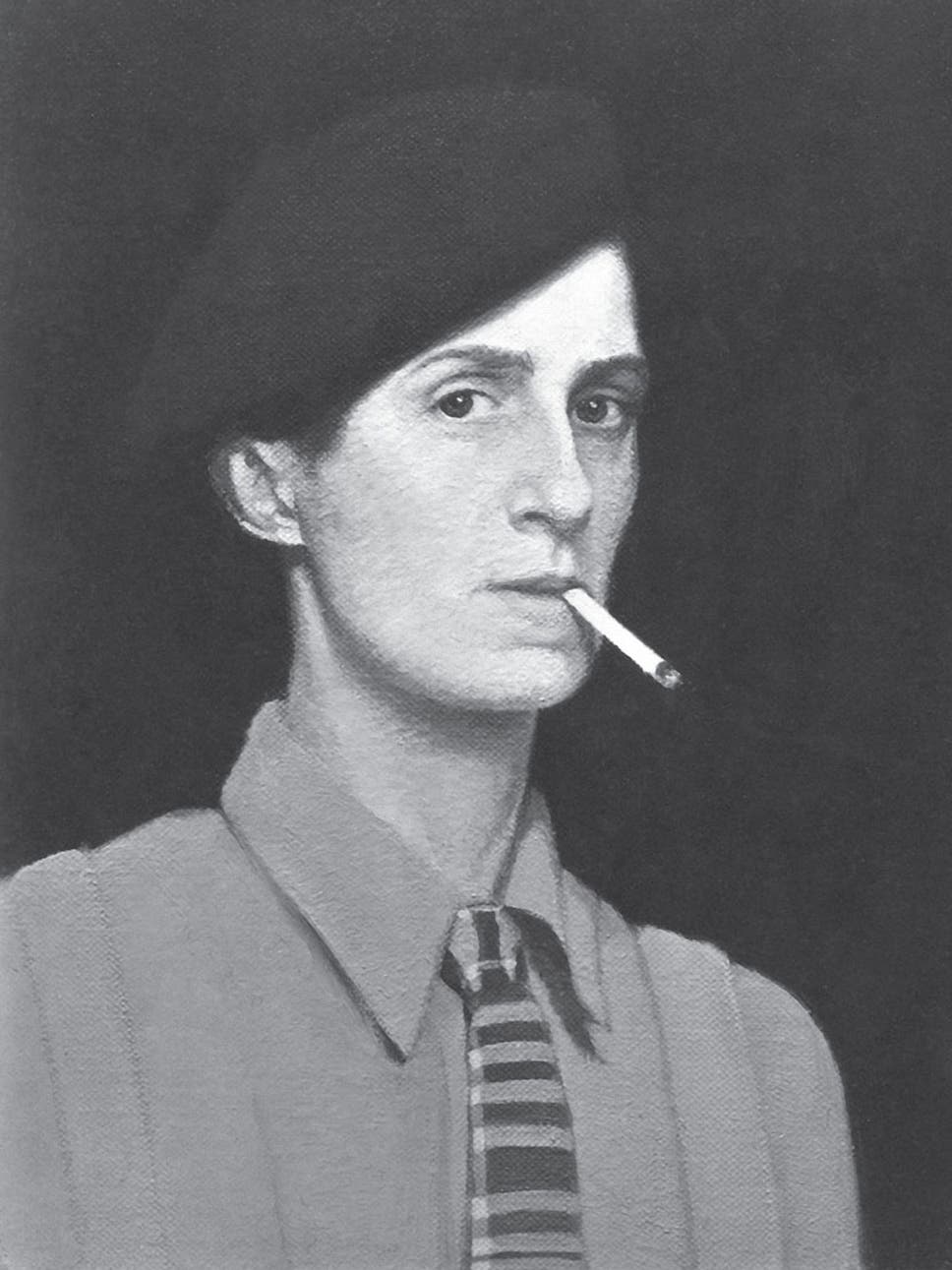

by Romaine Brooks, Peter (A Young English Girl), 1923-1924, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the artist, 1970.70

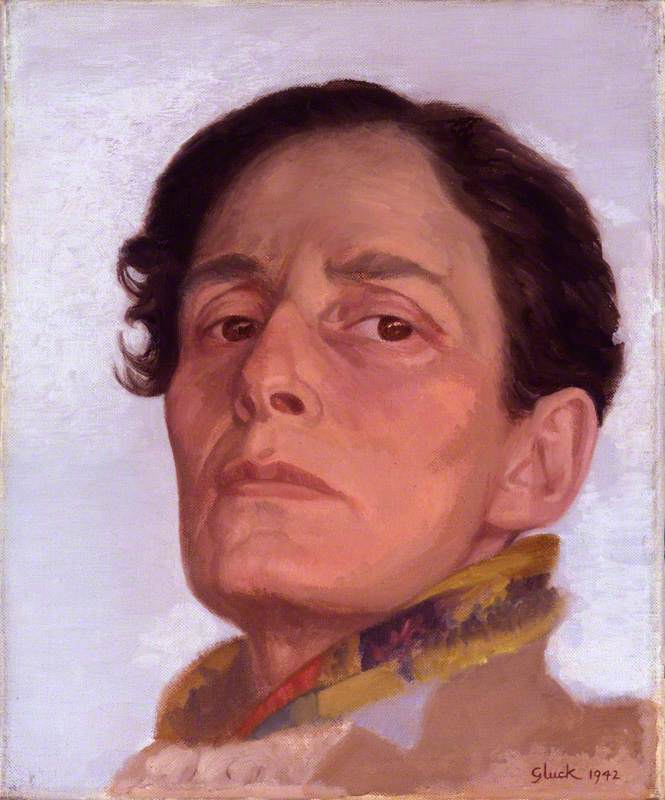

Gluck 1942

Gluck (1895–1978)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Lilac and Guelder Rose

Gluck (1895–1978)

Manchester Art Gallery

.jpg)

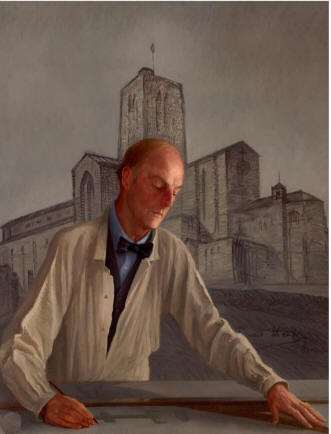

Medallion

Edward Maufe by Gluck

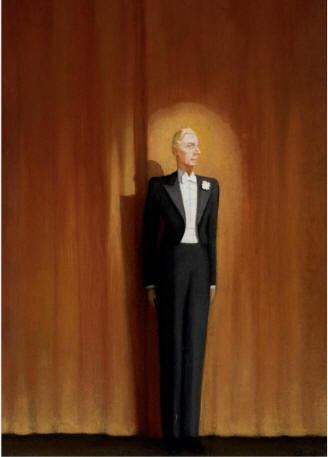

Ernst Thesiger, by Gluck

Constance Spry,

by Gluck

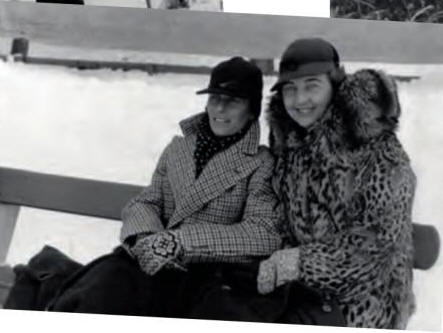

Nesta and Gluck, 1938-39

Gluck attended St John's Wood School of Art between 1913 and 1916 before moving to the west Cornwall valley of Lamorna and joining the artists' colony there.[1][2] Gluck moved to Cornwall with Craig (Miss E. M. Craig) who liked to be known by her masculine-sounding surname and who is believed to have been the artist’s first lover and two fellow art students. Today little is known about Craig, but her influence upon Gluck’s early life should not be overlooked – not least Hannah Gluckstein’s subsequent adoption of a neutral name. Indeed, Gluck loved to relate the tale of how they ‘ran away’ together to become artists and regarded this as a major life-changing event.

Gluck met artist Romaine Brooks in 1923, and the two agreed to sit for each other shortly thereafter, resulting in a portrait by Brooks, Peter (A Young English Girl), 1923-1924, and an unfinished one of Brooks by Gluck. Like Brooks, Gluck frequently wore clothing inspired by men's fashions that concealed her feminine figure. This androgynous attire was popular among upper- and upper-middle-class women at the time. It allowed them to experiment with fashion, but it also provided an outlet for lesbians, like Gluck and Brooks, to question traditional gender roles. In a 1918 letter to her brother, Gluck wrote of her new look, "I am flourishing in a new garb. Intensely exciting. Everybody likes it," and went on to say, "I hope you will like it because I intend to wear that sort of thing always." In her portrait, Gluck's striped waistcoat and silk tie, coupled with her closely cropped hair, help mask her gender, which is only confirmed with Brooks's title.

In the 1920s and 30s Gluck became known for portraits and floral paintings; the latter were favoured by the interior decorator Syrie Maugham. Gluck insisted on being known only as Gluck, "no prefix, suffix, or quotes", and when an art society of which she was vice president identified Gluck as "Miss Gluck" on its letterhead, Gluck resigned. Gluck identified with no artistic school or movement and showed her work only in solo exhibitions, where it was displayed in a special frame Gluck invented and patented. This Gluck-frame rose from the wall in three tiers; painted or papered to match the wall on which it hung, it made the artist's paintings look like part of the architecture of the room.

Gluck met society flower arranger and decorator Constance Spry in 1932 when designer and interior decorator Prudence Maufe sent Gluck an arrangement by Spry to paint. Spry was a leading figure in cultivating a fashion for white flowers, and often used Gluck's paintings to illustrate her articles. Many of Spry's customers also commissioned flower paintings from Gluck.

One of Gluck's best-known paintings, Medallion, is a dual portrait of Gluck and her lover, Nesta Obermer, inspired by a night in 1936 when she attended a Fritz Busch production of Mozart's Don Giovanni.[3] According to Gluck's biographer Diana Souhami, "They sat together in the third row and felt the intensity of the music fused them both into one person and matched their love." Gluck referred to it as the "YouWe" picture.[4] It was later used as the cover of a Virago Press edition of The Well of Loneliness.[5] Gluck also had a romantic relationship with author and socialite Sybil Cookson.[7]

Chantry House

In 1944 Gluck moved to Chantry House in Steyning, Sussex, living with her lover Edith Shackleton Heald until the latter's death in 1976.[8]

In the 1950s Gluck became dissatisfied with the artist's paints available and began a "paint war" to increase their quality. Ultimately, Gluck persuaded the British Standards Institution to create a new standard for oil paints; however, the campaign consumed Gluck's time and energy to the exclusion of painting for more than a decade. Gluck and Heald had a second home at Dolphin Cottage, in Lamorna.[9]

In her seventies, using special handmade paints supplied free by a manufacturer who had taken their exacting standards as a challenge, Gluck returned to painting and mounted another well-received solo show.[6] It was Gluck's first exhibition since 1937, and her last: she died in 1978.

Gluck's last major work was a painting of a decomposing fish head on the beach entitled Rage, Rage against the Dying of the Light.

My published books: