Wife Olive Custance, Partner Oscar Wilde

Queer Places:

Ham Hill House, Ham Ln, Powick, Worcester WR2 4RD, Regno Unito

35 Fourth Ave, Hove BN3 2PN, Regno Unito

Wixenford School, Ludgrove, Wokingham RG40 3AB, Regno Unito

Winchester College, College St, Winchester SO23 9NA, Regno Unito

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

26 Church Row, London NW3 6UP, Regno Unito

Friary Churchyard, Haslett Ave W, Crawley RH10 1HR, Regno Unito

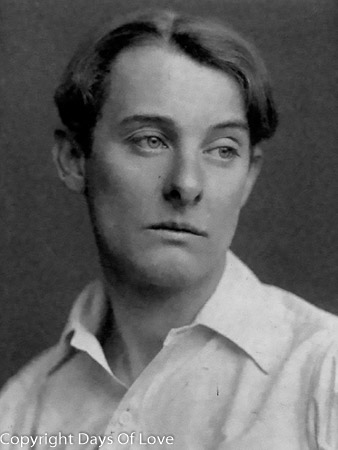

Lord

Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), nicknamed Bosie,

was a British author, poet, translator, and political commentator, better

known as the friend and lover of

Oscar Wilde. Much of his

early poetry was Uranian in theme, though he tended, later in life, to

distance himself from both Wilde's influence and his own role as a Uranian

poet. Politically he would describe himself as "a strong Conservative of the

'Diehard' variety".[1]

Two Loves (1894), In Praise of Shame

(1894) and Rondeau (1895) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade.

Lord

Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 1870 – 20 March 1945), nicknamed Bosie,

was a British author, poet, translator, and political commentator, better

known as the friend and lover of

Oscar Wilde. Much of his

early poetry was Uranian in theme, though he tended, later in life, to

distance himself from both Wilde's influence and his own role as a Uranian

poet. Politically he would describe himself as "a strong Conservative of the

'Diehard' variety".[1]

Two Loves (1894), In Praise of Shame

(1894) and Rondeau (1895) are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade.

In 1891, Douglas met Oscar Wilde; although the playwright was married with two sons, they soon began an affair.[12][13] In 1894, the Robert Hichens novel The Green Carnation was published. Said to be a roman à clef based on the relationship of Wilde and Douglas, it would be one of the texts used against Wilde during his trials in 1895.

Douglas has been described as spoiled, reckless, insolent and extravagant. He would spend money on men and gambling and expected Wilde to contribute to funding his tastes. They often argued and broke up, but would also always reconcile.

Douglas had praised Wilde's play Salome in the Oxford magazine, The Spirit Lamp, of which he was editor (and used as a covert means of gaining acceptance for homosexuality). Wilde had originally written Salomé in French, and in 1893 he commissioned Douglas to translate it into English. Douglas's French was very poor and his translation was highly criticised; for example, a passage that runs "On ne doit regarder que dans les miroirs" ("One should look only in mirrors") he rendered "One must not look at mirrors". Douglas was angered at Wilde's criticism, and claimed that the errors were in fact in Wilde's original play. This led to a hiatus in the relationship and a row between the two men, with angry messages being exchanged and even the involvement of the publisher John Lane and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley when they themselves objected to Douglas's work. Beardsley complained to Robbie Ross: "For one week the numbers of telegraph and messenger boys who came to the door was simply scandalous". Wilde redid much of the translation himself, but, in a gesture of reconciliation, suggested that Douglas be dedicated as the translator rather than credited, along with him, on the title-page. Accepting this, Douglas, somewhat vainly, likened a dedication to sharing the title-page as "the difference between a tribute of admiration from an artist and a receipt from a tradesman."[14]

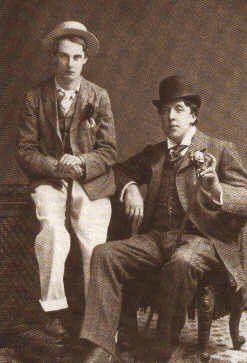

Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas

Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas

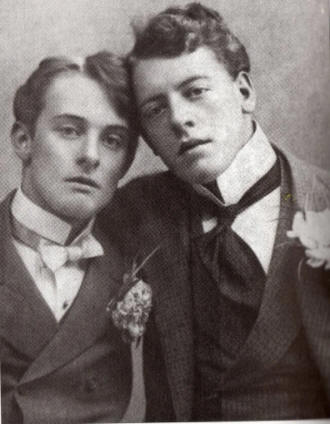

Alfred and Francis Douglas

Quisisana, Capri

Friary Churchyard, Crawley

On another occasion, while staying with Wilde in Brighton, Douglas fell ill with influenza and was nursed by Wilde, but failed to return the favour when Wilde himself fell ill in consequence. Instead Douglas moved to the Grand Hotel and, on Wilde's 40th birthday, sent him a letter saying that he had charged him the bill. Douglas also gave his old clothes to male prostitutes, but failed to remove from the pockets incriminating letters exchanged between him and Wilde, which were then used for blackmail.[14]

Alfred's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, suspected the liaison to be more than a friendship. He sent his son a letter, attacking him for leaving Oxford without a degree and failing to take up a proper career. He threatened to "disown [Alfred] and stop all money supplies". Alfred responded with a telegram stating: "What a funny little man you are".

Queensberry's next letter threatened his son with a "thrashing" and accused him of being "crazy". He also threatened to "make a public scandal in a way you little dream of" if he continued his relationship with Wilde.

Queensberry was well known for his temper and threatening to beat people with a horsewhip. Alfred sent his father a postcard stating "I detest you" and making it clear that he would take Wilde's side in a fight between him and the Marquess, "with a loaded revolver".

In answer Queensberry wrote to Alfred (whom he addressed as "You miserable creature") that he had divorced Alfred's mother in order not to "run the risk of bringing more creatures into the world like yourself" and that, when Alfred was a baby, "I cried over you the bitterest tears a man ever shed, that I had brought such a creature into the world, and unwittingly committed such a crime... You must be demented".

When Douglas's eldest brother Francis Viscount Drumlanrig died in a suspicious hunting accident in October 1894, rumours circulated that he had been having a homosexual relationship with the Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery, and that the cause of death was suicide. The Marquess of Queensberry thus embarked on a campaign to save his other son, and began a public persecution of Wilde. Wilde had been openly flamboyant, and his actions made the public suspicious even before the trial.[15] He and a minder confronted the playwright in his own home; later, Queensberry planned to throw rotten vegetables at Wilde during the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest, but, forewarned of this, the playwright was able to deny him access to the theatre.

Queensberry then publicly insulted Wilde by leaving, at the latter's club, a visiting card on which he had written: "For Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite (sic)". The wording is in dispute – the handwriting is unclear – although Hyde reports it as this. According to Merlin Holland, Wilde's grandson, it is more likely "Posing somdomite," while Queensberry himself claimed it to be "Posing as somdomite". Holland suggests that this wording ("posing [as] ...") would have been easier to defend in court.

After Wilde's death, Douglas established a close friendship with Olive Eleanor Custance, an heiress, poet and bisexual.[17] They married on 4 March 1902. Olive Custance was in a relationship with the writer Natalie Barney when she and Douglas first met.[18] Barney and Douglas eventually became close friends and Barney was even named godmother to their son, Raymond Wilfred Sholto Douglas, born on 17 November 1902.[19]

The marriage was stormy after Douglas became a Roman Catholic in 1911. They separated in 1913, lived together for a time in the 1920s after Olive also converted, and then lived apart after she gave up Catholicism. The health of their only child further strained the marriage, which by the end of the 1920s was all but over, although they never divorced.

The Canadian composer John Glassco did meet Lord Alfred Douglas in Paris in the 1920s and later said: ‘Never was there a more sociable man, a man with better manners or more exquisite grace of movement, speech and behaviour.’

As a fifteen-year-old schoolboy, the writer Denton Welch saw a grumpy old man on a train who turned out to be Lord Alfred Douglas. Welch later wrote: ‘I was thrilled. I had just read all about Oscar Wilde.’ For Welch, who was born in 1915, Wilde continued to be a significant cultural and erotic forebear. In his late twenties in July 1943, after chatting with a brace of bathing boys he wrote in his diary: ‘I began to think of Oscar Wilde … and all the people who have longed to become young again. I don’t know why 1890 should leap to my mind the whole time. Is it because they worshipped youth? Or is it because it always seems to me a rosy time for young men to be gay and wilful and wasteful?’

As a teenager, Samuel Steward, used to write to famous writers, hoping thereby to store up contacts that he would cash in in due course. He wanted to be a gay literary groupie, and, if we are to believe his memoirs, that is what he became. The year 1937 seems to have brought particular successes. For a start, he visited Alfred Douglas in the hope of making a sexual connection with Oscar Wilde through the irascible remnants of Bosie. At first, Douglas maintained decorum and disclaimed any homosexual interest – until they had a drink. ‘And that did it. Within an hour and a half we were in bed, the Church renounced, conscience vanquished, inhibitions overcome, revulsion conquered, pledges and vows and British laws all forgotten. Head down, my lips where Oscar’s had been, I knew that I had won.’ Thanking Steward afterwards, Douglas confided in him that all he and Oscar ever did was masturbate each other: ‘We kissed a lot, but not much more.’

In 1939 a petition to the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, asking for a Civil List pension for Alfred Douglas, was signed by James Agate, John Gielgud, Christopher Hassall, Harold Nicolson, Hugh Walpole, Evelyn Waugh, Virginia Woolf and others. It was apparently rejected, even after all those years, because of the Wilde scandal.

Douglas died of congestive heart failure in Lancing, Sussex, on 20 March 1945 at the age of 74. He was buried on 23 March at the Franciscan Friary, Crawley,[39] where he is interred alongside his mother, who had died on 31 October 1935 at the age of 91. A single gravestone covers them both.

The elderly Douglas, living in reduced circumstances in Hove in the 1940s, is mentioned in the diaries of Henry Channon and in the first autobiography of Donald Sinden, who, according to his son Marc, was one of only two people to attend his funeral.[40][41]

He died at the home of Edward and Sheila Colman. The couple were the main beneficiaries in his will, inheriting the copyright to Douglas's work. She endowed a memorial prize at Oxford in Douglas's name for the best Petrarchan sonnet.[42]

My published books: