Queer Places:

Lycée Henri-IV, 23 Rue Clovis, 75005 Paris, Francia

1021 Route du Château, 76280 Cuverville, Francia

51 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, London WC1H 0PN, UK

André

Paul Guillaume Gide (22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of

the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1947 "for his comprehensive and

artistically significant writings, in which human problems and

conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen

psychological

insight".[1]

Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of

anticolonialism between the two World Wars. The

author of "more than fifty books", at the time of his death the New

York Times obituary described him as "France's greatest contemporary

man of letters" and "judged the greatest French writer of this century

by the literary

cognoscenti."[2]

For André Gide, homosexual love was the ‘key’ to his life’s work, the

‘sphinx’ that led him to tackle all the other ‘sphinxes of conformity,

which my mind suspected of being the brothers and cousins of the first’.

André

Paul Guillaume Gide (22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of

the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1947 "for his comprehensive and

artistically significant writings, in which human problems and

conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen

psychological

insight".[1]

Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of

anticolonialism between the two World Wars. The

author of "more than fifty books", at the time of his death the New

York Times obituary described him as "France's greatest contemporary

man of letters" and "judged the greatest French writer of this century

by the literary

cognoscenti."[2]

For André Gide, homosexual love was the ‘key’ to his life’s work, the

‘sphinx’ that led him to tackle all the other ‘sphinxes of conformity,

which my mind suspected of being the brothers and cousins of the first’.

He befriended Oscar Wilde in Paris, and in 1895 Gide and Wilde met in Algiers. Wilde had the impression that he had introduced Gide to homosexuality, but, in fact, Gide had already discovered this on his own.[3][4] David Diamond's Psalm, an orchestral piece of that year, was inspired by a visit to Oscar Wilde’s grave in Père Lachaise and dedicated to André Gide.

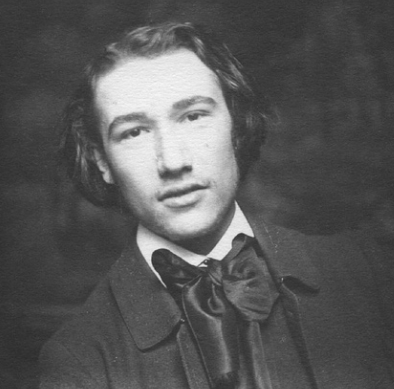

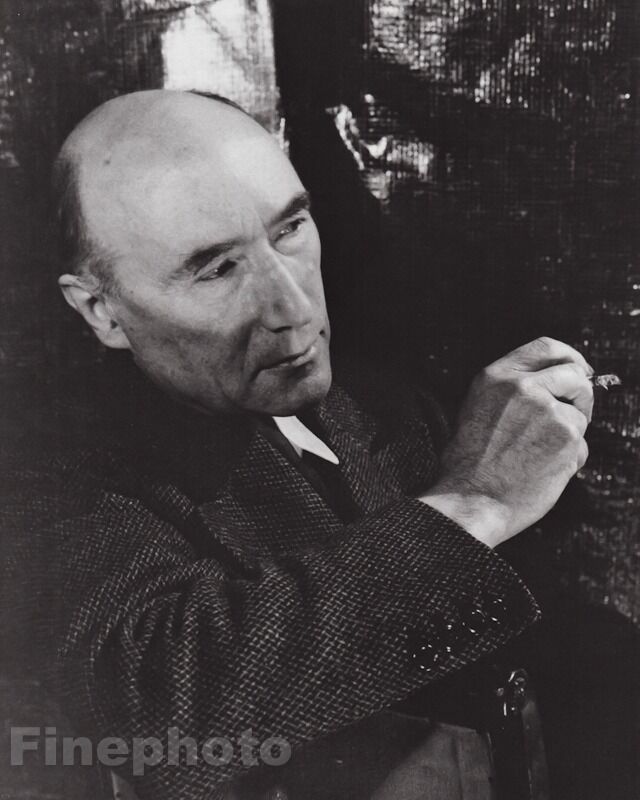

André Gide by Berenice Abbott

by George

Platt Lynes

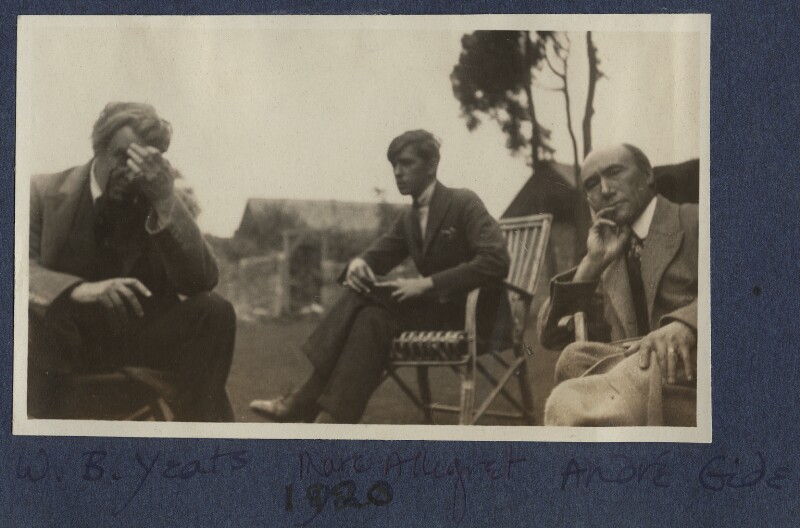

Marc Allégret and his lover André Gide, snapped by Ottoline Morrell, 1920

André Gide by Tamara de Lempicka

On 7 November 1932, in Berlin, Count Harry Kessler had dinner with the French novelist Roger Martin du Gard, among others. Kessler recorded the Frenchman’s impressions in his diary: It is his first visit and what fascinates him most is the life in the streets, ‘la Rue de Berlin’. The people he sees there seem to him quite different from those in Paris; the future is reflected in their looks. The new man, the man of the future, is being created in Germany … Martin du Gard is much impressed with the fine appearance of the German race. The handsome boys and beautiful young girls are, to him, a reincarnation of ancient Greece. Martin du Gard reported back to André Gide on the wonders and delights of Berlin, where he had found the young involved in ‘natural, gratuitous pleasures, sport, bathing, free love, games, [and] a truly pagan, Dionysiac freedom’. He spent most of his time there wandering around ‘the less salubrious districts of the city’, noticing (relative to Paris) the many prostitutes of both sexes and the ready availability of pornography. Encouraged by such reports, André Gide visited Berlin no fewer than five times in 1933. He, too, was delighted by, and seriously interested in, what he found there, although he did concede to Robert Levesque that Paris itself was slowly becoming more Berlin-like even if at the same time (to use that most erotically evocative of geographical terms) more ‘southern’. The two writers coincided in Berlin in October, Gide arriving for a fortnight, Martin du Gard for five weeks. They did their best to avoid each other on their forays into the sexual underworld, but always dutifully compared notes on what they had seen and experienced. Martin du Gard posed as a specialist in matters sexual in order to attend interviews with homosexual men at Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute. He also toured the gay clubs, nominating as his favourites the Hollandais and the lesbian Monocle. Christopher Isherwood was at Hirschfeld’s Institute on the day that Gide was given a guided tour, Gide ‘in full costume as The Great French Novelist, complete with cape’. Retrospectively calling him a ‘Sneering culture-conceited frog!’ from the safety of the mid-1970s – and in doing so sounding like a rather uptight, Francophobic D.H. Lawrence – Isherwood failed to consider that Gide’s pose might have been a way of giving Hirschfeld’s project the serious imprimatur of a symbolic cultural visit, to which the cape and the performed ‘greatness’ were essential embellishments.

Jef Last was involved in the early stages of COC. A communist writer he had published two novels containing representations of homo-sexual relationships – Zuiderzee (1934) and Huis zonder venster (1935), and he was invited to accompany André Gide on his celebrated visit to the Soviet Union in 1936.

Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide exposes to public view the conflict and eventual reconciliation of the two sides of his personality, split apart by a straitlaced traducing of education and a narrow social moralism. Gide's work can be seen as an investigation of freedom and empowerment in the face of moralistic and puritanical constraints, and centres on his continuous effort to achieve intellectual honesty. His self-exploratory texts reflect his search of how to be fully oneself, even to the point of owning one's sexual nature, without at the same time betraying one's values. His political activity is informed by the same ethos, as indicated by his repudiation of communism after his 1936 voyage to the USSR.

François Augiéras was a French writer. André Gide acted as one of his mentors. In 1944, Augiéras enlisted at the fleet depot in Toulon, then moved to Algeria. He hardly lingers in Algiers, in a hurry to go to the South, which he perceived to be his real country, and where he joined his uncle Marcel Augiéras, a retired colonial soldier, who lived in El Goléa, in the Sahara. During his stay in the Sahara, François Augiéras was sexually abused by his uncle, discovering on this occasion his own homosexual inclinations. Augiéras was inspired by this episode to write in 1949, Le Vieillard et l'Enfant, which he published on his own account under the pseudonym Abdallah Chaamba. The book caught the attention of André Gide who, a few months before his death, met the young writer after the latter had sent him two letters. Augiéras later described a Gide obviously moved by his meeting with him, and imagined himself as the "last love" of the great writer. Le Vieillard et l'Enfant was republished in 1954 by Éditions de Minuit and a rumor claimed that "Abdallah Chaamba" was a posthumous pseudonym of Gide.

My published books: