Queer Places:

200 Broadway, Rockland, ME 04841, Stati Uniti

Whitehall, 52 High St, Camden, ME 04843, Stati Uniti

Vassar College (Seven Sisters), 124 Raymond Ave, Poughkeepsie, NY 12604

75½ Bedford St, New York, NY 10014, USA

31 Chestnut St, Camden, ME 04843

Ragged Island, Harpswell, ME, Stati Uniti

Steepletop, 440 E Hill Rd, Austerlitz, NY 12017, Stati Uniti

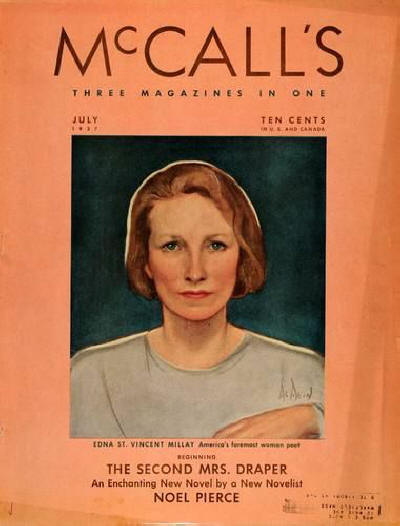

Edna

St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was

an American poet and playwright.[1]

Identified with the Lost Generation.

She lectured at Ferrer Center; Emma Goldman wrote

of her respect for Millay. Millay was arrested for protesting the execution of

Sacco & Vanzetti; she was the sister of Kathleen Millay.

Edna

St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was

an American poet and playwright.[1]

Identified with the Lost Generation.

She lectured at Ferrer Center; Emma Goldman wrote

of her respect for Millay. Millay was arrested for protesting the execution of

Sacco & Vanzetti; she was the sister of Kathleen Millay.

St Vincent Millary received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923, the third woman to win the award for poetry,[2] and was also known for her feminist activism. She used the pseudonym Nancy Boyd for her prose work. The poet Richard Wilbur asserted, "She wrote some of the best sonnets of the century."[3]

Millay was born in Rockland, Maine, to Cora Lounella Buzelle, a nurse, and Henry Tolman Millay, a schoolteacher who would later become a superintendent of schools. Her middle name derives from St. Vincent's Hospital in New York, where her uncle's life had been saved just before her birth. The family's house was "between the mountains and the sea where baskets of apples and drying herbs on the porch mingled their scents with those of the neighboring pine woods." In 1904, Cora officially divorced Millay's father for financial irresponsibility, but they had already been separated for some years. Cora and her three daughters, Edna (who called herself "Vincent"), Norma Lounella (born 1893), and Kathleen Kalloch (born 1896), moved from town to town, living in poverty. Cora travelled with a trunk full of classic literature, including Shakespeare and Milton, which she read to her children. The family settled in a small house on the property of Cora's aunt in Camden, Maine, where Millay would write the first of the poems that would bring her literary fame.

The three sisters were independent and spoke their minds, which did not always sit well with the authority figures in their lives. Millay's grade school principal, offended by her frank attitudes, refused to call her Vincent. Instead, he called her by any woman's name that started with a V.[4] At Camden High School, Millay began developing her literary talents, starting at the school's literary magazine, ''The Megunticook''. At 14 she won the St. Nicholas Gold Badge for poetry, and by 15, she had published her poetry in the popular children's magazine ''St. Nicholas'', the ''Camden Herald'', and the high-profile anthology ''Current Literature''. While at school, she had several relationships with women, including Edith Wynne Matthison, who would go on to become an actress in silent films.[5]

Edna St. Vincent Millay, 1914. Photo by

Arnold Genthe

Photographed on January 14, 1933, by

Carl Van Vechten

Edna left with Vassar

College friend Corinne Sawyer, circa 1914

Edna with Arthur Ficke and

Inez Millholland

Edna with her husband

Eugen Boissevain

Edna St Vincent Millay by Neysa McMein

75½ Bedford St, New York, NY 10014

White Horse Tavern, New York City

Steepletop, Austerlitz, MA

Millay entered Vassar College in 1913 when she was 21 years old, later than usual. She had relationships with several fellow students during her time there and kept scrapbooks including drafts of plays written during the period.[6]

After her graduation from Vassar in 1917, Millay moved to New York City. She lived in a number of places in Greenwich Village, including a house owned by the Cherry Lane Theatre[7] and 75½ Bedford Street, renowned for being the narrowest[8][9] in New York City.[10] The critic Floyd Dell wrote that the red-haired and beautiful Millay was "a frivolous young woman, with a brand-new pair of dancing slippers and a mouth like a valentine." Millay described her life in New York as "very, very poor and very, very merry." While establishing her career as a poet, Millay initially worked with the Provincetown Players on Macdougal Street and the Theatre Guild.

The editors of Poetry, Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin Henderson included in their 1917 selection for The New Poetry: An Anthology poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay. According to Adrienne Munich and Melissa Bradshaw, authors of Amy Lowell, American Modern, what connects these poets is their appartenance to the queer sisterhood.

In 1924 Millay and others founded the Cherry Lane Theater "to continue the staging of experimental drama."[11] Magazine articles under a pseudonym also helped support her early days in the village.

Counted among Millay's close friends were the writers Witter Bynner, Arthur Davison Ficke, and Susan Glaspell, as well as Floyd Dell and the critic Edmund Wilson. Brynner, Dell and Wilson proposed marriage to her and were refused.[12] Edna's trysts include: Allan Ross Macdougall (future editor of Edna’s collected letters); the writer Scudder Middleton; the musician Harrison Dowd; and Rollo Peters, an artist connected with the Theatre Guild.

Millay's fame began in 1912 when she entered her poem "Renascence" in a poetry contest in ''The Lyric Year''. The poem was widely considered the best submission and when it was ultimately awarded fourth place, it created a scandal which brought Millay publicity. The first-place winner Orrick Johns was among those who felt that "Renascence" was the best poem, and stated that "the award was as much an embarrassment to me as a triumph". A second-prize winner offered Millay his $250 prize money.[13] In the immediate aftermath of the ''Lyric Year'' controversy, wealthy arts patron Caroline B. Dow heard Millay reciting her poetry and playing the piano at the Whitehall Inn in Camden, Maine, and was so impressed that she offered to pay for Millay's education at Vassar College.[14]

Her 1920 collection ''A Few Figs From Thistles'' drew controversy for its exploration of female sexuality and feminism.[15] In 1919 she wrote the anti-war play ''Aria da Capo'' which starred her sister Norma Millay at the Provincetown Playhouse in New York City. Millay won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923 for "The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver";[16] she was the third woman to win the poetry prize, after Sara Teasdale (1918) and Margaret Widdemer (1919).[17]

In January 1921, she went to Paris, where she met and befriended the sculptor Thelma Wood.[18] Veiled references to an affair she had with Thelma Wood, the love of Djunas Barnes’ life, appear in certain memoirs from the period, though only selectively and not in Edna’s own journals. (Apparently the affair occurred sometimes in 1922 during Edna’s difficult year in Paris.)

In 1923 she married 43-year-old Eugen Jan Boissevain (1880–1949), the widower of the labor lawyer and war correspondent Inez Milholland, a political icon Millay had met during her time at Vassar. A self-proclaimed feminist, Boissevain supported her career and took primary care of domestic responsibilities. Both Millay and Boissevain had other lovers throughout their twenty-six-year marriage. For Millay, a significant such relationship was with the poet George Dillon. She met Dillon at one of her readings at the University of Chicago in 1928 where he was a student. He was fourteen years her junior, and the relationship inspired the sonnets in the collection ''Fatal Interview'' (published 1931).[19]

In 1925, Boissevain and Millay bought Steepletop near Austerlitz, New York, which had been a blueberry farm.[20] The couple built a barn (from a Sears Roebuck kit), and then a writing cabin and a tennis court. Millay grew her own vegetables in a small garden.[21] The couple later bought Ragged Island in Casco Bay, Maine, as a summer retreat.

In 1928, Emma Goldman began writing her autobiography, with the support of a group of American admirers, including Edna St. Vincent Millay, journalist H. L. Mencken, novelist Theodore Dreiser and art collector Peggy Guggenheim, who raised $4,000 for her.

During the first world war Millay had been a dedicated and active pacifist; however, from 1940 she supported the Allied Forces, writing in celebration of the war effort and later working with Writers' War Board to create propaganda, including poetry.[22] Her reputation in poetry circles was damaged by her war work. Merle Rubin noted: "She seems to have caught more flak from the literary critics for supporting democracy than Ezra Pound did for championing fascism."[23]

In 1943 Millay was the sixth person and the second woman to be awarded the Frost Medal for her lifetime contribution to American poetry.

Boissevain died in 1949 of lung cancer, and Millay lived alone for the last year of her life.

Millay died at her home on October 19, 1950. She had fallen down stairs and was found approximately eight hours after her death. Her physician reported that she had suffered a heart attack following a coronary occlusion.[24] She was 58 years old. She is buried alongside her husband at Millay Colony for the Arts, Austerlitz, New York.[25]

Millay's sister Norma and her husband, the painter and actor Charles Frederick Ellis, moved to Steepletop after Millay's death. In 1973, they established Millay Colony for the Arts on the seven acres around the house and barn. After the death of her husband in 1976, Norma continued to run the program until her death in 1986.

At 17, the poet Mary Oliver visited Steepletop and became a close friend of Norma. Oliver eventually lived there for seven years and helped to organize Millay's papers.[26] Mary Oliver herself went on to become a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, greatly inspired by Millay's work.[27] In 2006, the state of New York paid $1.69 million to acquire Steepletop, with the intention to add the land to a nearby state forest preserve. The proceeds of the sale were to be used by the Edna St. Vincent Millay Society to restore the farmhouse and grounds and turn it into a museum. The museum has been open to the public since summer 2010, and guided tours of Steepletop and Millay's gardens are available from the end of May through the middle of October. Parts of the grounds of Steepletop, including the Millay Poetry Trail that leads to her grave, are now open to the public year-round.

Details of Millay's life were compiled by biographer Nancy Milford in the book titled ''Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St Vincent Millay'', published in 2001. Milford was sought out by Millay's only living connection at the time, her sister Norma Millay Ellis, and was chosen for her previous, successful biography ''Zelda''. Milford would then go on to edit and write an introduction for a collection of Millay's poems called ''The Selected Poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay.''[28]

In 2015, she was named by Equality Forum as one of their 31 Icons of the 2015 LGBT History Month.[29]

Tennessee Williams (1911-1983), Roddy Bottum (born 1963) and Edna St. Vincent Millay (1893-1950), all descend from the same Pilgrims, Stephen Tracy and his wife Tryphosa Less, and Stephen Hopkins (arrived with the Mayflower).

Tony

Scupham-Bilton - Mayflower 400 Queer Bloodlines

My published books: