Partner Eugene McCown, Maurice Grosser

Queer Places:

Yaddo, 312 Union Ave, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866, Stati Uniti

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Fontainebleau Schools, 77300 Fontainebleau, Francia

Conservatoire de Paris, 209 Avenue Jean Jaurès, 75019 Paris, Francia

MacDowell Colony, 100 High St, Peterborough, NH 03458

Hotel Chelsea, 222 W 23rd St, New York, NY 10011, Stati Uniti

Rehoboth Cemetery, Slater, MO 65349, Stati Uniti

Virgil

Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and

critic. One of the most unusual aspects of the

Stettheimers’ salon was

the large number of their gay, bisexual, and lesbian friends and

acquaintances, who were comfortable being their authentic selves among their

straight friends.

Several of the sisters’ closest friends, including

Charles Demuth,

Marsden Hartley,

Henry McBride,

Virgil Thomson, and Baron

Adolph de Meyer (married to a lesbian,

Olga Carracciolo) were homosexual;

Carl Van Vechten,

Cecil Beaton, and

Georgia O’Keeffe were bisexual;

Natalie Barney and

Romaine Brooks were lesbians; and

Alfred Stieglitz,

Marcel Duchamp,

Gaston Lachaise, Marie Sterner, and

Leo Stein were heterosexual. This open, natural mix of friends with different sexual preferences continued when Stettheimer held salons in her studio in the Beaux Arts building in midtown Manhattan, although later in life she also had parties where most of the guests were strong feminist women.

Virgil

Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and

critic. One of the most unusual aspects of the

Stettheimers’ salon was

the large number of their gay, bisexual, and lesbian friends and

acquaintances, who were comfortable being their authentic selves among their

straight friends.

Several of the sisters’ closest friends, including

Charles Demuth,

Marsden Hartley,

Henry McBride,

Virgil Thomson, and Baron

Adolph de Meyer (married to a lesbian,

Olga Carracciolo) were homosexual;

Carl Van Vechten,

Cecil Beaton, and

Georgia O’Keeffe were bisexual;

Natalie Barney and

Romaine Brooks were lesbians; and

Alfred Stieglitz,

Marcel Duchamp,

Gaston Lachaise, Marie Sterner, and

Leo Stein were heterosexual. This open, natural mix of friends with different sexual preferences continued when Stettheimer held salons in her studio in the Beaux Arts building in midtown Manhattan, although later in life she also had parties where most of the guests were strong feminist women.

Addressing the post-WWI period in his enormous overview of twentieth-century music, but without the ulterior agenda of the anti-gay conspiracy theorists, Alex Ross writes: Homosexual men, who make up approximately 3 to 5 percent of the general population, have played a disproportionately large role in composition of the last hundred years. Somewhere around half of the major American composers of the twentieth century seem to have been homosexual or bisexual: Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Samuel Barber, Marc Blitzstein, John Cage, Harry Partch, Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, Gian Carlo Menotti, David Diamond, and Ned Rorem, among many others.

A number of composers who were both Jewish and gay had something else in common. In their youth, they had been to Paris to study composition under Nadia Boulanger: Aaron Copland in the early 1920s, Virgil Thomson in the mid-1920s (while there he met his lover, the painter Maurice Grosser), Marc Blitzstein in the late 1920s (his Russian-born lover, the conductor Alexander Smallens accompanied him to Europe in 1924), David Diamond in 1936 (his Psalm, an orchestral piece of that year, was inspired by a visit to Oscar Wilde’s grave in Père Lachaise and dedicated to André Gide).

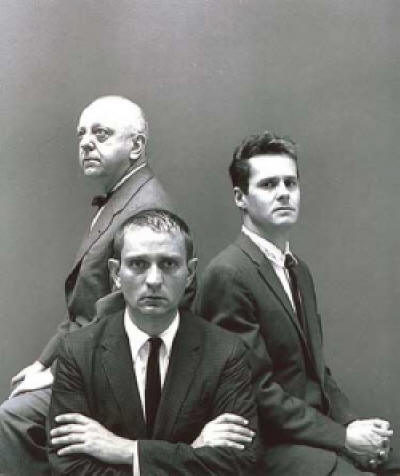

Virgil Thomson, William Flanagan and Ned Rorem

Bronze Head of Tom Irwin from Estate of Virgil Thomson by Edward Melcarth (28 cm. Ht)

.jpg)

Hotel Chelsea, New York City

Virgil Thomson was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist,[1][2][3][4][5] a neoromantic,[6] a neoclassicist,[7] and a composer of "an Olympian blend of humanity and detachment"[8] whose "expressive voice was always carefully muted" until his late opera Lord Byron which, in contrast to all his previous work, exhibited an emotional content that rises to "moments of real passion".[9]

Thomson was born in Kansas City, Missouri. As a child, he befriended Alice Smith, great-granddaughter of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter-day Saint movement. During his youth, he often played the organ in Grace Church, (now Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral), as his piano teacher was the church's organist. After World War I, he entered Harvard University thanks to a loan from Dr. Fred M. Smith, the president of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and father of Alice Smith. Eventually he discovered the Liberal Club, an organization for Jews, socialists, and the penniless who did not otherwise fit into the school’s social environment. There Thomson met Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the great architectural historian, and Maurice Grosser, Thomson’s lifelong lover, though during their time at the Liberal Club they barely knew each other.

His tours of Europe with the Harvard Glee Club helped nurture his desire to return there. At Harvard, Thomson focused his studies on the piano work of Erik Satie. He studied in Paris on fellowship for a year, and after graduating, lived in Paris from 1925 until 1940. He eventually studied with Nadia Boulanger and became a fixture of "Paris in the twenties."

Eugene McCown moved to Paris in July of 1921 where he resided for the next 12 years before returning to New York. In Paris, he made a living by painting and and playing piano at Le Boeuf. According to Thomson, one of his live-in lovers: He plays jazz on the piano nights (10 till 2) at Le Boeuf, which is the rendezvous of Jean Cocteau, Les Six, and les snobs intellectuals--a not unassuming place frequented by English upper-class, bohemians, wealthy Americans, French aristocrats...He plays remarkably well and is the talk as well as the toast of Paris. He paints afternoons and has recently had a sudden access of financial success.... I take my social life vicariously now…Thru Eugene. I almost never go out. I practice the organ, do counterpoint and write music. I mostly eat alone and seldom see Gene except mornings. ("Virgil Thomson: Composer on the Aisle" by Anthony Tommasini, pg. 100)

A. Everett Austin, Jr met Virgil Thomson when the latter was briefly back at Harvard as a teaching assistant in 1925.

In 1925, in Paris, Thomson cemented a relationship with painter Maurice Grosser, who was to become his life partner and frequent collaborator. Later he and Grosser lived at the Hotel Chelsea, where he presided over a largely gay salon that attracted many of the leading figures in music and art and theater, including Leonard Bernstein, Tennessee Williams, and many others. He also encouraged many younger composers and literary figures such as Ned Rorem, Lou Harrison, John Cage, Frank O'Hara, and Paul Bowles. Grosser died in 1986, three years before Thomson.[10]

During a 1929 visit to New York, Virgil Thomson had gone to Harlem with Henry-Russell Hitchcock to see the famous black entertainer, Jimmie Daniels, perform. Inspired, Thomson decided to have an all-black cast for Four Saints. There were other consequences from that night. Daniels would become "the first Mrs. Johnson," Philip Johnson's lover.

His most important friend from this period was Gertrude Stein, who was an artistic collaborator and mentor to him. In 1934 Stein and Thomson completed the opera Four Saints, and Grosser developed the scenario that provided the framework for its first production. The opera was produced by Arthur Everett Austin, a bisexual Harvard man who had a major impact on the arts. On the night of the premier, "the slim, graceful figure taking a bow, with his playful blue eyes and brilliantined hair, a gardenia in the lapel of his dinner jacket, was handsome enough to have stepped from the silver screen or out of a Noël Coward play." Nicknamed "Chick", Austin used his looks and charms on both men and women. Frederick Ashton choreographed the show (his American debut) and John Houseman directed (his first time directing). The production is famous for the celebrities who went to see it. Guests at the premier included Alexander Caldor, Buckminster Fuller, Clare Boothe, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. They and other attendees were said to have come by "private railway car, airplane, and Rolls-Royce; even, as one observer suggested, by jeweled pogo stick."

When it opened in New York, Four Saints became the longest running opera in Broadway history. The opera took the city by storm. "Decorated for Easter Sunday, the most prestigious windows along Fifth Avenue evoked Florine Stettheimer's sets: Elizabeth Arden showed Saint Teresa with an Easter egg, Bergdorf Goodman depicted Saint Teresa singing "April Fool's Day a pleasure", and Lord & Taylor and others followed suit.

Following the publication of his book, The State of Music, Thomson established himself in New York City as a peer of Aaron Copland, and was also a music critic for the New York Herald-Tribune from 1940 to 1954.[11]

His definition of music was famously "that which musicians do,"[12] and his views on music are radical in their insistence on reducing the rarefied aesthetics of music to market activity. He even went so far as to claim that the style a piece was written in could be most effectively understood as a consequence of its income source.[13]

In 1960 at Smith College the growing scandal which involved Newton Arvin, threatened also to engulf America’s preeminent architectural historian, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, another Harvard luminary. Hitchcock, in Werth’s words, was “a high-toned WASP with Rabelaisian appetites … [who] openly entertained a large circle of young homosexual faculty members from area colleges who idolized him.” As it turned out, Hitchcock’s papers included explicitly homosexual correspondence from the noted American composer and New York Herald-Tribune music critic Virgil Thomson, and might just as easily have contained similar letters from Hitchcock’s other close friends, architect Philip Johnson and Lincoln Kirstein, founder of the New York City Ballet.

In 1969, Thompson composed Metropolitan Museum Fanfare: Portrait Of An American Artist to accompany the Museum's Centennial exhibition "New York Painting And Sculpture: 1940–1970."[14][15]

Thomson became a sort of mentor and father figure to a new generation of American tonal composers such as Ned Rorem, Paul Bowles and Leonard Bernstein, a circle united as much by their shared homosexuality as by their similar compositional sensibilities.[16] Women composers were not part of that circle, and one writer has suggested that, as a critic, he selectively omitted mention of their works, or adopted a more passive tone when praising them.[17]

Thomson was a recipient of Yale University's Sanford Medal.[18] In 1988, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[19] He was a National Patron of Delta Omicron, an international professional music fraternity.[20]

Thomson died on September 30, 1989, in his suite at the Hotel Chelsea in Manhattan, aged 92. He had lived at the Chelsea for close to 50 years.[21]

My published books: