Partner Mabel Batten and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge, buried together with Batten

Queer Places:

King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, UK

Sunny Lawn, 6 Durley Rd, Bournemouth BH2 5JL, UK

The Forecastle, Hucksteps Row, Church Square, Rye TN31 7HG, UK

The Mermaid Inn, Mermaid St, Rye TN31 7EY, UK

Santa Maria, West St, Rye TN31 7ES, UK

8 Watchbell St, Rye TN31 7HA, UK

Black Boy, 4 High St, Rye TN31 7JE, UK

14 Addison Rd, Kensington, London W14, UK

Kensington Church St, London W8 4LF, UK

Shelley Court, 56 Tite St, Chelsea, London SW3 4JB, UK

59 Cadogan Square, Chelsea, London SW1X 0HZ, UK

1 Swan Walk, Chelsea, London SW3 4JJ, UK

22 Draycott Ave, Chelsea, London SW3 3AA, UK

7 Trevor Square, Knightsbridge, London SW7 1DT, UK

10 Sterling St, Knightsbridge, London SW7 1HN, UK

37 Holland St, Kensington, London W8 4LX, UK

Kensington Palace, Kensington Gardens, Kensington, London W8 4PX, UK

98 St Martin's Ln, London WC2N, UK

502 Dolphin Square East Side, Pimlico, London SW1V, UK

Highgate Cemetery, Swain's Ln, Highgate, London N6 6PJ, UK

Hall–Carpenter Archives, 230 Bishopsgate, London EC2M 4QH, UK

Marguerite

Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and

author. She is best known for the novel The Well of Loneliness, a

groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. Djuna Barnes wrote a

lively bagatelle called Ladies Almanack in 1928.

Natalie Barney

featured here as Dame Evangeline Musset;

Romaine Brooks as Cynic Sal;

Lily de Gramont as

the Duchesse Clitoressa of Natescourt;

Una

Troubridge as Lady Buck-and-Balk;

Radclyffe Hall as Tilly Tweed-in-blood;

Mina Loy as Patience Scalpel;

Mimì Franchetti as Senorita

Fly-About; and Janet Flanner

and Solita Solano as Nip and Tuck. The

book was privately published by Robert

McAlmon. Hall appears as Hermina de Randan in Extraordinary Women

(1928) by Compton Mackenzie.

Marguerite

Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and

author. She is best known for the novel The Well of Loneliness, a

groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. Djuna Barnes wrote a

lively bagatelle called Ladies Almanack in 1928.

Natalie Barney

featured here as Dame Evangeline Musset;

Romaine Brooks as Cynic Sal;

Lily de Gramont as

the Duchesse Clitoressa of Natescourt;

Una

Troubridge as Lady Buck-and-Balk;

Radclyffe Hall as Tilly Tweed-in-blood;

Mina Loy as Patience Scalpel;

Mimì Franchetti as Senorita

Fly-About; and Janet Flanner

and Solita Solano as Nip and Tuck. The

book was privately published by Robert

McAlmon. Hall appears as Hermina de Randan in Extraordinary Women

(1928) by Compton Mackenzie.

A number of novels were published in the years after the First World War, which tackled the theme of lesbianism and brought the issue to a wider audience. The most influential of these was Radclyffe Hall's novel The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928, whose trial and subsequent banning for obscenity was the subject of widespread press attention. The decade also saw the formation of explicitly lesbian communities such as the expatriate lesbian community of the Parisian left bank, while individual self-identified lesbians, including Radclyffe Hall and the artist Gluck, employed clothing and mannerism to express themselves as lesbian. The Well of Loneliness depicted the experiences of a female invert, Stephen Gordon, in a hostile society.

After meeting Una Troubridge in 1915, Radclyffe Hall discovered the happy irony that there could be greater freedom in a lesbian relationship than in a sanctioned alliance.

As a financially independent woman, Radclyffe Hall could afford to risk social disapproval by being open about her sexuality, and she began to do so as soon as she reached maturity. However, it was not until 1918, when she began her lifelong relationship with Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge, the former wife of Lord Admiral Troubridge, that Hall's lesbianism became notorious. As the wife of an admiral, Una Troubridge held an important social position, and her desertion of her husband for a woman inevitably caused a scandal. However, as Laura Doan has stressed, mannish tailored fashions for women were the height of modern fashion in the 1920s and Radclyffe Hall was able to buy her masculine evening suits from the ladies' tailors at Harrods.

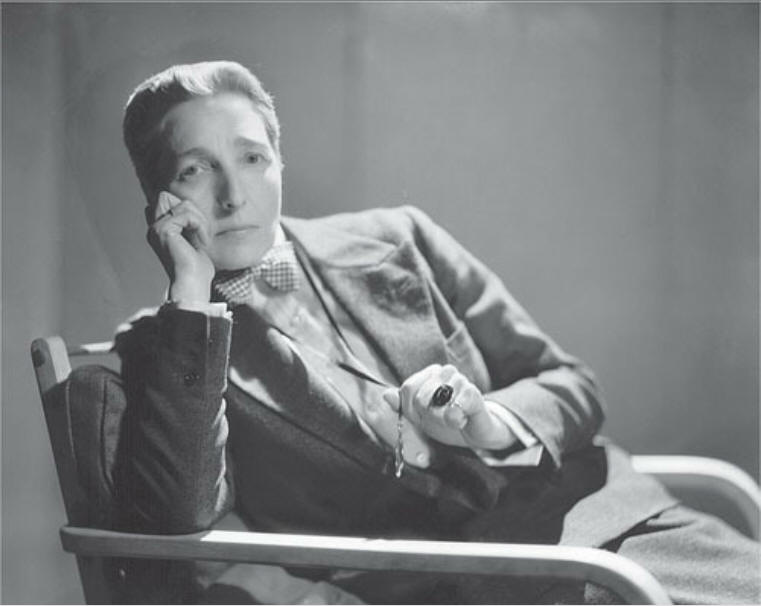

Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge at the Ladies' Kennel Club Dog Show,

Ranelagh, 1920

Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubrigde at Crufts, 1923

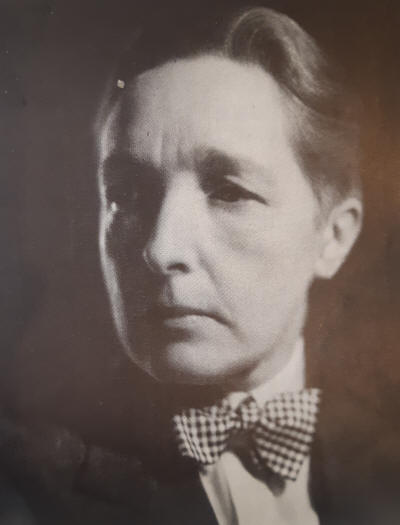

Radclyffe Hall in The Bookman, May 1927

Radclyffe Hall 1918

Charles A. Buchel (1872–1950)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Private View (1937) by Gladys Hines.

Mrs George Batten Singing by John Singer Sargent. It was later willed

by Mabel Batten to her lover, Radclyffe Hall.

Sunny Lawn, 6 Durley Rd, Bournemouth

Associate of of Hall and her lover Una Troubridge included Gwen Farrar, an actor, who gave a dance in June 1923 at which they met Teddie Gerard. Troubridge, recalling her meeting with ‘John’, as Radclyffe Hall had been named by her first (female) lover, remembered the ‘rough country clothes; heavy short-skirted tweeds unusual in those days, collars and ties and … a queer little green Heath hat’. Troubridge herself was monocled and shingled and wore trousers.

Marguerite Radclyffe Hall was born in 1880 at "Sunny Lawn", Durley Road, Bournemouth, Hampshire (now Dorset),[1] to a wealthy philandering father, Radclyffe Radclyffe-Hall, and an unstable mother, Mary Jane Diehl.[2] Her stepfather was the professor of singing Albert Visetti, whom she did not like and who had a tempestuous relationship with her mother.[3][4] Hall was a lesbian[5] and described herself as a "congenital invert", a term taken from the writings of Havelock Ellis and other turn-of-the-century sexologists. Having reached adulthood without a vocation, she spent much of her twenties pursuing women she eventually lost to marriage.

In 1907 at the Bad Homburg spa in Germany, Hall met Mabel Batten, a well-known amateur singer of lieder. Batten (nicknamed "Ladye") was 51 to Hall's 27, and was married with an adult daughter and grandchildren. They fell in love, and after Batten's husband died they set up residence together. Batten gave Hall the nickname John, which she used the rest of her life.[6]

In 1915 Hall fell in love with Mabel Batten's cousin Una Troubridge (1887–1963), a sculptor who was the wife of Vice-Admiral Ernest Troubridge, and the mother of a young daughter. When Batten died in 1916, Hall had Batten's corpse embalmed and a silver crucifix blessed by the pope laid on it.[7] Hall, Batten and Troubridge were "undeterred by the Church's admonitions on same-sex relationships. Hall's Catholicism sat beside a life-long attachment to spiritualism and reincarnation."[8] In 1917, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge began living together.[9]

In 1920, Radclyffe Hall instituted proceedings against St John Lane Fox-Pitt, a member of the council of the Society for Psychical Research to which she aspired to be elected. He had referred to her as ‘a grossly immoral woman’. There was a case to be made against Radclyffe Hall, and Fox-Pitt might have been the man to make it: he was the son-in-law of the very Marquess of Queensberry who had done for Oscar Wilde, and he shared many of Queensberry’s worst habits of demonstrative moral outrage and self-righteousness. But he drew back. He claimed that he had never intended any slur on Hall’s sexual morality; he had been referring only to her psychic research.

The year after the Fox-Pitt libel trial, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge moved from the country, where they had been breeding dachshunds, into London. As they eased themselves into the cultural scene, they began meeting fellow lesbians, such as the writers May Sinclair and Vere Hutchinson. (Not that Surrey was empty of such women: they had met the composer Ethel Smyth on a golf course and gone to tea and dinner with her.) The painter Romaine Brooks courted Hall for a while, but to no avail. Undeterred, she invited the couple to visit her in the Villa Cercola on Capri. But Hall and Troubridge both liked Romaine Brooks, even if Brooks was upset by the portrayal of herself in Hall’s first novel, The Forge (1924), and even if Troubridge hated the portrait Brooks painted of her. At about the same time, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge met Tallulah Bankhead and her current lover Gwen Farrar; Bankhead invited them as special guests to her first night in The Green Hat at the Comedy Theatre.

From 1924 to 1929 Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge lived at 37 Holland Street, Kensington, London.[10]

In the summer of 1926, notwithstanding their usual misgivings, Hall and Troubridge allowed Natalie Barney to show them around some of the main lesbian clubs in Paris: the Select, the Regina and the Dingo. They made a special trip to Passy to lay flowers on Renée Vivien’s grave.

Hall wrote The Well of Loneliness in 1928. As usual, it contained sketches of people she knew: Noël Coward as Jonathan Brockett, for instance, and Natalie Barney as Valérie Seymour. Many prominent readers found the book boring or ridiculous. T.E. Lawrence said of it, in a letter to E.M. Forster, ‘I read The Well of Loneliness: and was just a little bored. Much ado about nothing.’ When The Well of Loneliness was published in 1928, the first reviews were generally respectful, if not especially enthusiastic. But none of them – by, among others, Arnold Bennett, Vera Brittain, Cyril Connolly, L.P. Hartley and Leonard Woolf – took exception to the subject matter. When the book was banished, Leonard Woolf and E.M. Forster rallied to defend the principle of freedom of speech, but Radclyffe Hall was not satisfied. Virginia Woolf takes up the story in a letter, dated 30 August 1928, to Vita Sackville-West: "Morgan [Forster] goes to see Radclyffe in her tower in Kensington, with her love [Una Troubridge]: and Radclyffe scolds him like a fishwife, and says that she won’t have any letter written about her book unless it mentions the fact that it is a work of artistic merit – even genius. And no one has read her book; or can read it: and now we have to explain this to all the great signed names – Arnold Bennett and so on. So our ardour in the case of freedom of speech gradually cools, and instead of offering to reprint the masterpiece, we are already beginning to wish it unwritten." The jury awarded costs against Hall and she had to sell the John Singer Sargent portrait of her late lover Mabel Batten. Radclyffe Hall had been devastated by the fact that she was never called to give evidence in favour of her own work, and, of course, by the eventual judgment against The Well. As she said in a letter to Havelock Ellis, ‘In the eyes of the law I am non existent.’

Writing in 1958, Beverley Nichols said the word ‘homosexual’ was not widely known in Britain in the 1920s. ‘Today the word is so common that one would hardly be surprised to see it over the entrance to one of the departments in a general store. But in the twenties it was taboo, and I think it is correct to say that the first time it began to come into general circulation was during the case of The Well of Loneliness, by Radclyffe Hall.’

The teenage Quentin Crisp, looking around him for cultural signs of what he felt he was about to become, found a few in newspaper accounts of court cases and in show-business gossip. According to these signs, homosexuality: was thought to be Greek in origin, smaller than socialism but more deadly – especially to children. At about this time The Well of Loneliness was banned. The widely reported court case, together with the extraordinary reputation that Tallulah Bankhead was painstakingly building up for herself as a delinquent, brought Lesbianism, if not into the light of day, at least into the twilight, but I do not remember ever hearing anyone discuss the subject except Mrs Longhurst and my mother.

When Mary Allen and Helen Tagart were introduced to Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge in 1930, Troubridge recorded in her diary that Allen thought "the authorities were against her because she was an invert."

The relationship of Hall and Una Troubridge would last until Hall's death. In 1934 Hall fell in love with Russian émigrée Evguenia Souline and embarked upon a long-term affair with her, which Troubridge painfully tolerated.[11] Hall became involved in affairs with other women throughout the years.[12][13]

Hall lived with Troubridge in London and, during the 1930s, in the tiny town of Rye, East Sussex, noted for its many writers, including her contemporary the novelist E. F. Benson. At Rye there were several lesbian households nearby, among them Edith Craig living with Christopher St. John (aka Christabel Marshall ) and Clare "Tony" Atwood; Lady Maud Warrender and Marcia van Dresser; and Mary Allen, pioneer policewoman, with Miss Taggart.

In Rye, Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge bought a house, where they could live in relative seclusion but not in isolation. E.F. Benson lived down the road in Henry James’ former home, Lamb House. Noël Coward and his boyfriend Jeffery Amherst came to tea. London was easily accessible for further socialising, as when they had supper there with John Gielgud and his friend John Perry.

Mary Renault described reading The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall aloud to her lover accompanied by rather heartless laughter, while on holiday ina French fishing village in 1938. The Well of Loneliness, she claimed, carried an impermissible allowance of self-pity, and its earnest humourlessness invites irreverence.

Hall died at age 63 of colon cancer, and is interred at Highgate Cemetery in North London at the entrance of the chamber of the Batten family, where Mabel is buried as well.

In 1930, Hall received the Gold Medal of the Eichelbergher Humane Award. She was a member of the PEN club, the Council of the Society for Psychical Research and a fellow of the Zoological Society.[14] Radclyffe Hall was listed at number sixteen in the top 500 lesbian and gay heroes in The Pink Paper.[15]

My published books: