Queer Places:

249 Edgerton St, Rochester, NY 14607

88 Jane St, New York, NY 10014

544 Hudson St, New York, NY 10014

Yaddo, 312 Union Ave, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866

David

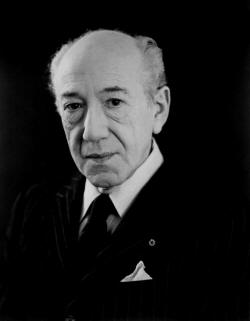

Leo Diamond (July 9, 1915 – June 13, 2005) was one of the leading American classical music

composers of the twentieth century. His music is melodic and lyrical at the same time that it jumps with

modern energy. It began to be widely appreciated in the 1940s.

Since Diamond was openly gay and fiercely outspoken when he confronted discrimination and stupidity, he

also made his share of enemies in the conservative musical milieu of the 1940s and 1950s. His music fell out

of critical favor for three decades, but he lived to see renewed appreciation of his work, which since the

1980s has enjoyed a long-overdue revival among audiences yearning for beautiful music.

David

Leo Diamond (July 9, 1915 – June 13, 2005) was one of the leading American classical music

composers of the twentieth century. His music is melodic and lyrical at the same time that it jumps with

modern energy. It began to be widely appreciated in the 1940s.

Since Diamond was openly gay and fiercely outspoken when he confronted discrimination and stupidity, he

also made his share of enemies in the conservative musical milieu of the 1940s and 1950s. His music fell out

of critical favor for three decades, but he lived to see renewed appreciation of his work, which since the

1980s has enjoyed a long-overdue revival among audiences yearning for beautiful music.

Addressing the post-WWI period in his enormous overview of twentieth-century music, but without the ulterior agenda of the anti-gay conspiracy theorists, Alex Ross writes: Homosexual men, who make up approximately 3 to 5 percent of the general population, have played a disproportionately large role in composition of the last hundred years. Somewhere around half of the major American composers of the twentieth century seem to have been homosexual or bisexual: Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Samuel Barber, Marc Blitzstein, John Cage, Harry Partch, Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, Gian Carlo Menotti, David Diamond, and Ned Rorem, among many others.

A number of composers who were both Jewish and gay had something else in common. In their youth, they had been to Paris to study composition under Nadia Boulanger: Aaron Copland in the early 1920s, Virgil Thomson in the mid-1920s (while there he met his lover, the painter Maurice Grosser), Marc Blitzstein in the late 1920s (his Russian-born lover, the conductor Alexander Smallens accompanied him to Europe in 1924), David Diamond in 1936 (his Psalm, an orchestral piece of that year, was inspired by a visit to Oscar Wilde’s grave in Père Lachaise and dedicated to André Gide).

544 Hudson St

88 Jane St

The composer David Diamond had been spoilt for America by his trips to France in the 1930s. Having won a scholarship in 1935 to travel to Paris and study composition under Nadia Boulanger, he stayed until the outbreak of war, making friends with such Modernist greats as Igor Stravinsky, Picasso and Joyce. As well as these European expatriates – not to mention Frenchmen such as Maurice Ravel and André Gide – he also benefited from encounters with Paris’s cornucopia of American escapees such as Carson McCullers, Georgia O’Keeffe and the by now Americanised Greta Garbo, all three of whom became his close friends.

David Diamond was born on July 9, 1915 in Rochester, New York. Very early on, he demonstrated undeniable musical talent. His parents, Jewish immigrants from Poland and Austria, were probably not prepared when their five-year-old picked up a violin and started playing as if he had already had lessons. Certainly they were not ready or able to pay for a prodigy's instruments and lessons on their meager earnings as a carpenter and dressmaker. As fortune would have it, Diamond was given a violin as well as lessons in the public school he attended. When his family moved to Cleveland in 1927, André de Ribaurpierre of the Cleveland Institute of Music volunteered to teach him violin and composition for free. In 1928, the 13-year-old Diamond also received a different kind of support. Upon learning that French composer Maurice Ravel was a visiting artist with the Cleveland Orchestra, Diamond went to Ravel's hotel to show him some of his compositions. Ravel was encouraging. He told him, "Young man, you must come to Paris and study with Nadia Boulanger." At the time, Diamond had never heard of the famous teacher. Music might have been the prime connection between Diamond and Ravel, but they were also attuned to each other's dapper style. Diamond later said, "I think [Ravel] was interested because of my purple turtleneck sweaters." Diamond was no less enthusiastic about Ravel's sartorial flair; he recalled the composer conducting in "a peculiar checkered suit, with yellow shoes, purple socks, a green shirt and a purple bow tie." Support for Diamond's early musical training continued when his family moved back to Rochester in 1929; he was given a scholarship to the preparatory division of the Eastman School of Music, where he studied violin with Effie Knauss and composition with Bernard Rogers. After Diamond graduated from high school, he entered the undergraduate program at the Eastman School of Music. The School at the time was headed by composer Howard Hanson, a man who reportedly disliked Jews, homosexuals, and modernists. Diamond, who never hid his gayness, would have drawn Hanson's hostility on all three fronts, and some people have hypothesized that the brevity of his one-year stay at Eastman can be explained by the unwelcoming atmosphere Hanson created. Whatever the cause, Diamond moved to New York in 1934 and studied on scholarship with noted composer Roger Sessions privately and at the New Music School until 1937. As he was learning more about composition and rhythm, the spell that French music continued to cast over him showed up in Hommage à Satie (1934), one of his first published compositions and his first work performed in New York.

In 1936 at the age of 21, Diamond at last made his first trip to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger. Her teaching methods led him to a close analysis of scores by Ravel and Johann Sebastian Bach. His time with her was highly productive compositionally. A visit to Oscar Wilde's grave in Paris inspired his orchestral piece Psalm (1936). Dedicated to French novelist André Gide, this work won the Juilliard Publication Award in 1938 and was performed by many orchestras at the time. Diamond's Parisian sojourn was also socially rewarding; he befriended some of the city's leading artistic lights, including André Gide, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein, as well as composers Albert Roussel and Igor Stravinsky. It was also at this time that his work found an appreciative sponsor in conductor Charles Munch. Munch would later program his work with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Despite increasing command of his art and a greatly expanded circle of influential friends, life was not one triumph after another for Diamond. In 1938, for example, when he applied for a teaching position at Columbia University, he received the odd advice to "stop wearing turtleneck sweaters." Diamond interpreted that remark as a veiled allusion to his homosexuality and a forewarning of the rejection he was about to receive. His response was to return to Paris for more composition study.

With war clouds on the horizon in 1939, Diamond returned to New York and embarked on what would prove to be the most celebrated period of his career. The New York Philharmonic under conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos premiered his First Symphony in 1941 when he was 26, and his compositions were championed and introduced by prominent and influential conductors, including Leopold Stokowski, Pierre Monteux, Serge Koussevitzky, and Leonard Bernstein. In 1944, with the fear, tensions, and privations of World War II uppermost on everyone's mind, Mitropoulos commissioned a work with the request, "These are distressing times. Most of the difficult music I play is distressing. Make me happy." In response, Diamond composed his Rounds for Strings (1944), about which New York Times music critic Olin Downs commented, "There is laughter in the music and no waste notes." The piece became an audience favorite.

Diamond often questioned why, out of all of his enormous output, Rounds for Strings had to be his bestknown work and stand above his other pieces. His complaint about this triumph, whether justified or not, did not earn much sympathy, especially from those who had never had a real success themselves. Hence, Diamond began to be seen as overly self-involved in some circles. Indeed, his strong personality, frankness, and occasionally erratic behavior all combined to gain him a reputation for being difficult. Sensitive and vulnerable to criticism, Diamond was sometimes volatile, often blunt, and, once, famously violent. On being ejected from a 1943 rehearsal of his Second Symphony by the New York Philharmonic's music director Artur Rodzinski, Diamond retired for a few drinks at the Russian Tea Room and, when Rodzinski entered, punched him in the nose. This incident led Aaron Copland, Bernstein, and others to organize a fund so that Diamond could begin psychoanalysis. His friends' concerns about anger management did not silence the composer, however. He himself has admitted, "I was a highly emotional young man, very honest in my behavior, and I would say things in public that would cause a scene between me and, for instance, a conductor." His sharp tongue and strong opinions made him enemies then and in the future.

Although Diamond's work was being programmed regularly by leading orchestras in the 1940s, he had by no means secured financial success. He had to play violin in the Hit Parade radio orchestra and for Broadway shows to make ends meet. Another development in the classical music scene that affected Diamond's career was the advent and rise of serialism, based on repeated 12-tone patterns, atonal music, and unstructured aleatoric music, like that of John Cage. Diamond's neoclassical style, which combined a melodic line with sharply syncopated rhythms in an impeccably orchestrated and complex classical musical structure, was dismissed as old-fashioned by this group of ambitious newcomers, who would dominate classical music composition from the 1950s to about 1980. Diamond also blamed anti-Semitism and homophobia for his fall from critical favor.

David Diamond wrote his Third Quartet in memory of Allela Cornell: “The young woman I was living with, a fabulous painter by the name of Allela Cornell, became depressed while I was conducting performances of my music for Margaret Webster's production of Shakespeare's The Tempest. When I got home one night, I saw them bringing a stretcher down from the loft that we shared at 544 Hudson St, New York, NY 10014, and, of course, the moment I got near the ambulance, they said they were taking her to St. Vincent's. So I immediately ran over to the hospital which was diagonally across 7th Avenue, and when I got there, she was in the Diagnostic Room. She had a friend who was a photographer and who had hydrochloric acid in the woodshed for developing her film, and Allela in her depression had gone out there and drunk almost half a bottle of the acid, and for one whole year she was a dying wraith; she weighed twenty-four pounds on the last day of her life. And yet she was drawing in bed at St.Vincent's, drawings which I have with me still.” Cornell died for the conseguences of her attempted suicide in October 1946.

In 1951, Diamond was appointed Fulbright professor at the University of Rome. In Italy, he was able to escape the nasty infighting of the New York classical music world for a while. Upon a return visit to the United States, however, he was served a subpoena by the House Un-American Activities Committee, a consequence of Diamond's earlier interest in communism. Refusing to honor the subpoena, he chose to return to Italy. He settled in Florence and remained there until 1965. One fascinating non-musical byproduct of his years of exile is the key role he played in the first staging of Edward Albee's The Zoo Story. While living in Italy, Diamond read the script of Albee's one-act play that many New York producers had turned down. He was enthusiastic and forwarded the script to a friend, German actor Pinkas Braun. Braun then arranged for the world premiere in Berlin (and in German) on September 28, 1959 of this landmark in American theatrical history.

When Diamond returned to the United States in 1965, he became head of the composition department at the Manhattan School of Music. He remained in the position until 1967. In 1973, he began teaching at the Juilliard School of Music, where he enjoyed a long teaching career, remaining on the Juilliard faculty until 1997.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Diamond's work was mostly ignored by the new conductors who assumed the helm of the major orchestras. With characteristic candor, he told the New York Times in 1975 that "Conductors today are appallingly lazy. What a sad fact that these rude young men are inheriting the finest orchestras!" In the 1980s and 1990s, however, classical music fashion took another turn. The traditional tonal system, along with the traditional musical values of harmony and melody, regained its place at the center of classical music. With this change of fashion, Diamond was rediscovered and his music found new critical appreciation. Two of his students from Juilliard, conductor Gerard Schwarz and cellist Stephen Honigberg, were particularly responsible for reviving interest in Diamond's work. Schwarz, music director of the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, has singled Diamond out as the most talented composer of his generation and backed up that assertion with acclaimed recordings.

Despite a period of being overshadowed by lesser composers, Diamond ultimately achieved wide recognition. Indeed, the sustained quality of Diamond's astonishing output (11 symphonies, 11 string quartets, over 50 preludes and fugues for piano, and many more works from 65 years of composing) brought him a long list of prizes, including three Guggenheim Fellowships; the Paderewski Prize in 1943; a Prix de Rome from the American Academy in Rome; Columbia University's prestigious William Schuman Award for his life's work in 1985; and the National Medal of Arts, which was presented by President Clinton at the White House in 1995. In a 1990 interview, Diamond expressed quiet satisfaction at his vindication, noting of the period in which he was ignored by critics and conductors, "I don't look back in anger because I feel that I've won the battle. The others have disappeared." Diamond's Second Symphony (1944), Fourth Symphony (1948) and Orchestral Suite for Romeo and Juliet (1947), among many other works, are now regularly performed for enthusiastic audiences by orchestras around the world. Diamond died of congestive heart failure in Rochester, New York on June 13, 2005, a few weeks before his 90th birthday. He had reportedly completed a draft of his autobiography and was working with an editor to prepare it for publication. Up in the air is the question of whether a Golden Years perspective might have prompted him to sanitize or tone down the juicier details of incidents such as Leonard Bernstein's habit of stealing his boyfriends. Almost certainly, however, his autobiography elaborates on his artistic credo, stated in a May 2005 interview with music critic Melinda Bargreen: "If music doesn't communicate, it has no chance of survival. The need for beautiful music is stronger now than ever."

My published books: