Partner Pavel Tchelitchew

Queer Places:

View Office, 1 E 53rd St, New York, NY 10022

360 E 55th St, New York, NY 10022

Dakota Apartments, 1 W 72nd St, New York, NY 10023, Stati Uniti

Rose Hill Cemetery, Brookhaven, Mississippi 39601, Stati Uniti

Charles Henri Ford[1] (February 10, 1908 – September 27, 2002) was an American poet, novelist, diarist, filmmaker, photographer, and collage artist. He published more than a dozen collections of poetry, exhibited his artwork in Europe and the United States, edited the Surrealist magazine ''View'' (1940–1947) in New York City, and directed an experimental film. He was the partner of the artist Pavel Tchelitchew.

Painter Leonor Fini did an opulent

and highly flattering portrait of Charles Henri Ford.

Charles Henri Ford[1] (February 10, 1908 – September 27, 2002) was an American poet, novelist, diarist, filmmaker, photographer, and collage artist. He published more than a dozen collections of poetry, exhibited his artwork in Europe and the United States, edited the Surrealist magazine ''View'' (1940–1947) in New York City, and directed an experimental film. He was the partner of the artist Pavel Tchelitchew.

Painter Leonor Fini did an opulent

and highly flattering portrait of Charles Henri Ford.

Charles Henry Ford was born in Brookhaven, Mississippi, on February 10, 1908, the son of Charles Ford, who owned hotels in four towns in the South, and Gertrude Cato, an artist.[1] . Alhough the family was Baptist, he was sent to Catholic boarding schools. Actress Ruth Ford was his sister and only known sibling. ''The New Yorker'' published one of his poems in 1927, before he turned 20,[2] under the name Charles Henri Ford, which he had adopted to counter the assumption that he was related to the business magnate Henry Ford. He dropped out of high school and published several issues of a monthly magazine, ''Blues: A Magazine of New Rhythms'', in 1929 and 1930, with Parker Tyler.[3]

Not long after, he became part of Gertrude Stein's salon in Paris, where he met Natalie Clifford Barney, Man Ray, Kay Boyle, Janet Flanner, Peggy Guggenheim, Djuna Barnes, and others of the American expatriate community in Montparnasse and Saint-Germain-des-Près. He had an affair with Djuna Barnes and they visited Tangiers together. He went to Morocco in 1932 at the suggestion of Paul Bowles, and there he typed Barnes's just-completed novel, ''Nightwood'' (1936), for her.

With Parker Tyler, who later became a highly respected film critic, he co-authored ''The Young and Evil'' (1933), an experimental novel with debts to the prose of Djuna Barnes and Gertrude Stein. Stein wrote a blurb for the novel that said "''The Young and Evil'' creates this generation as ''This Side of Paradise'' by Fitzgerald created his generation."[4] Tyler later described it as "the novel that beat the beat generation by a generation".[5] Louis Kronenberger, in the novel's only U.S. review, described it as "the first candid, gloves-off account of more or less professional young homosexuals".[6] [7] Edith Sitwell burned her copy and described it as "entirely without soul, like a dead fish stinking in hell". The novel portrays a collection of young genderqueer artists as they write poems, have sex, move in and out of cheap rented rooms, and explore the many speakeasies in their Greenwich Village neighborhood. The characters' gender and sexual identities are presented candidly. It was rejected by several American and British publishers before Obelisk Press in Paris agreed to publish it. Officials in the U.K. and U.S. prevented shipments of the novel from reaching bookstores.

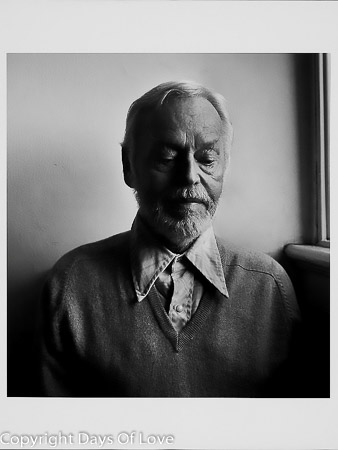

Featured in

Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay

and Lesbian Writers by Robert Giard [Rights Notice: Copyright Jonathan G. Silin (jsilin@optonline.net)]

Charles Henri Ford, by Pavel Tchelitchew

Charles Henri

Ford emerges, satisfied, from one of the vespasiennes of Paris: a mischievous

portrait by Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1935.

Dakota Apartments, 1 W 72nd St, New York, NY 10023, Stati Uniti

Ford returned to New York City in 1934 and brought Pavel Tchelitchew, his partner, with him. Ford's circle at the time included Carl Van Vechten, Glenway Wescott, George Platt Lynes, Lincoln Kirstein, Orson Welles, George Balanchine, and E. E. Cummings. Charles Henri Ford and Pavel Tchelitchew had a guest house on the estate of Alice De Lamar. Visiting friends from abroad included Cecil Beaton, Leonor Fini, George Hoyningen-Huene, and Salvador Dalí. Beaton's photographs of Ford represented a departure from his fine art portraits of royalty and celebrities. In one Ford posed "on a bed of tabloid newspapers", symbols of the violence and excess of American culture, in an exploration of low culture with homoerotic undertones that drew on Ford's "sexually transgressive image".[8]

Jean Connolly moved in an entourage of young male couples that included Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby, Tony Bower and Cuthbert Worsley, Peter Watson and Denham Fouts, Brian Howard and Toni Altmann. "Drink, night life, tarts and Tonys," complained Cyril Connolly, who referred to the whole entourage as "Pansyhalla." They liked Picasso, Marcel Proust, and Francis Poulenc, favored in architecture the Baroque, admired Josephine Baker and jazz. Someone took a copy of Dwight Ripley's Poems to Jean Cocteau, who responded "Quel néurophate!", a diagnosis that Rupert relayed with wicked relish. When Gerald Heard published two books in 1931 to propose that evolution demanded an evolved human consciousness, Brian Howard called them "the most important that have ever been written since the Ice Age." In Pansyhalla, a compelling example was set by Peter Watson, who joined with Cyril Connolly in 1939 to found Horizon and then financed that influential journal thoughout its career. Until the WWII, Watson lived mostly in Paris; a portrait of Jean Connolly, by Man Ray, was in his apartment. In 1938 he subsized the publication of a first book of poems by Charles Henri Ford, the young poet who was painter Pavel Tchelitchew's lover, and who, back in New York by 1940, would found a counterpart to Horizon, the trendier but likewise influential magazine View. It was View that brought John Bernard Myers from Buffalo to be its managing editor, and Myers who, as director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery that Dwight himself sponsored, acted as impresario for a cast of painters and poets that seems now, to typify the postwar New York scene.

Ford published his first full-length book of poems, ''The Garden of Disorder'' in 1938. William Carlos Williams wrote the introduction.[9] When Ford discussed the concept of poetry, he highlighted its relationship with other forms of art. Ford said, "Everything is related to the concept of poetry. As you know, Jean Cocteau used to talk about the poetry of the novel, the poetry of the essay, the poetry of the theater—everything he did, he said, was poetry. Well, he was one of my gurus."[10] While some of his poetry is easily recognizable as surrealist–"the pink bee storing in your brain's/veins a gee-gaw honey for the golden skillet"–he also adapted his style to political poetry. He published in ''New Masses'' and gave voice to a black man confronting a lynch mob: "Now I climb death's tree./The pruning hooks of many mouths/cut the black-leaved boughs./The robins of my eyes hover where/sixteen leaves fall that were a prayer."

In 1940, Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler collaborated again on the magazine ''View'' devoted to avant-garde and surrealist art. It "took full advantage of the European Surrealists roosting in New York during the war" to establish New York as a center of surrealism. The magazine was published quarterly, as finances permitted, until 1947. It attracted contributions from artists such as Pavel Tchelitchew, Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, André Masson, Pablo Picasso, Henry Miller, Paul Klee, Albert Camus, Lawrence Durrell, Georgia O'Keeffe, Man Ray, Jorge Luis Borges, Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, Marc Chagall, Jean Genet, René Magritte, Jean Dubuffet, and Edouard Roditi. It printed the work of Max Ernst, Man Ray and Isamu Noguchi as its cover art.[11] In the 1940s, View Editions, the publishing arm of the quarterly, published the first monograph on Marcel Duchamp and a collection of André Breton's poems in a bi-lingual edition, ''Young Cherry Trees Secured Against Hares'' (1946).[12]

Once Tennessee Williams paid a visit to the office of View. They were all gathered in Charles Henri Ford's room, Ford sitting on his desk, a pile of books to be reviewed at his side, while in his hand he held a copy of Neverheless by Marianne Moore. "Who," he was asking, "should write a price about this?" Williams spoke up. "You know, Charlie," he said, "I think I could do a real nice review of Marianne Moore." Ford looked at him in astonishment and then in deepest Columbus, Mississippi, drawl he said, "Why, Tinn, can yew read?"

Alice De Lamar thought it would be nice if the 5th birthday of View was to be celebrated on her estate in Weston, CT. Charles Henri Ford thought it a wonderful notion, and since it was near Halloween, the celebration was a costume ball with Pavel Tchelitchew creating the decorations. Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, taking their cue from Tchelitchew's beatiful drawings for Hide and Seek, were dressed as leaf children, with finishing touches by Tchelitchew.

Ford's book of poems ''Sleep in a Nest of Flames'' (1959) contained a preface by Dame Edith Sitwell.[13] Ford and Tchelitchew moved to Europe in 1952, and in 1955 Ford had a photo exhibition, ''Thirty Images from Italy'', at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts.[14] In Paris the next year he had his first one-man show of paintings and drawings. Jean Cocteau wrote the foreword to the catalog.[15] In 1957, Tchelitchew died in Rome.

In the summer of 1946, John Bernard Myers performed a puppet show at Spivy’s Roof in New York. He asked Charles Henri Ford to write a puppet play for him, and Ford then suggested he also ask Jane Bowles for a sketch and Paul Bowles to write some music for both. Myers was friendly with Kurt Seligmann, who made the puppets. Ford’s sketch for three characters was called A Sentimental Playlet and involved a clown, a sailor and a wild-haired lady. Bowles’ play was called A Quarreling Pair and had two sisters who lived in separate rooms, one room very messy and the other room very neat. John Latouche came to Myers after the performance, full of effusive congratulations, and shortly after that Myers was taken to Mary McCarthy’s table; she said she had enjoyed the show. When Myers went out to the terrace for some fresh air, a friend beckoned him to a table, where he met Ned Rorem and his companion Maggie von Maggerstadt. Rorem said he too would like to compose some songs for puppets if Myers ever did another show.

In 1946 Charles Henri Ford wrote Chanson pour Billie, a poem to the singer Billie Holiday.

Ruth Ford’s connection to William Faulkner did not begin in October 1948, though her actions during Faulkner’s lost weekend lionized her presence in his life. Ford entered Faulkner’s life much earlier, as a coed at the University of Mississippi in 1929–1930. A native of Hazlehurst, Mississippi, Ford attended Ole Miss at approximately the same time as Faulkner’s brother, Dean. Estelle claimed that Dean and Ford dated and that Dean, a talented painter, had Estelle and Ford sit for him. Victoria (Cho-Cho), barely a teenager at the time, disputed that any relationship existed between Dean and Ford, but Estelle would tell in 1963 that this relationship, though it “never became truly serious apparently,” is why Faulkner not only wrote Requiem for a Nun for Ford, but also why he gave her the stage rights with very little requirement on her part for payments to option it until it finally appeared ten years after his initial offer. Ford told that Dean introduced her to his brother, a struggling writer at the time. Barbara Izard, whose work on the history of the production of Requiem also serves as a biography of Ford, recounts, however, that Faulkner introduced himself to Ford, roughly around the time he was composing As I Lay Dying. According to Izard, Faulkner approached Ford in the local Oxford landmark, the Tea Hound, to tell her “‘You have a very fine face,’ Then without further comment, he turned and went back to his table”. In 1948 Ford was living in New York and working in Broadway productions but traveling often to Boston to work for the Brattle Theater Company, where, in the early 1950s, she would first attempt to stage Requiem with the help of her brother’s lover as the set designer. The novel was published in 1951. On 15 September 1951, the New York Times announced that Faulkner was working with producer Lemuel Ayers on a stage version of the play to feature Ruth Ford, whom, according to the columnist, Faulkner “had in mind for his leading feminine character.” Unfortunately, the production was profoundly delayed. Albert Marre, who was supposed to direct the production in 1951, would cite trouble between Ford’s vision and the Brattle’s interests as the source of the problem. Ford insisted that her brother’s partner, Pavel Tchelitchew, be the set designer. According to Marre, in the spring of 1952 Tchelitchew, Ford’s brother Charles Henri-Ford, and Ford had a falling out over their creative differences, which led to the death of this first attempt at producing a stage version of the play. Concerning all this theater drama, Marre claimed that “William Faulkner didn’t concern himself” with Ford’s decision to turn over set design to her brother’s homosexual partner. The creative differences, however, were between the management of the Brattle Theater Company and the Fords (including Charles’s life partner Pavel), not between Ford and Tchelitchew. Indeed, Faulkner had surely met both Tchelitchew and Charles Henri-Ford during his frequent trips to New York from 1948 to 1952, most likely at the famed social gatherings hosted by the couple in their apartment. Izard charts the history of the weekly salons hosted in Henri-Ford’s apartment in the New York landmark, the Dakota, where Ruth Ford would also live until her death in 2009. Though these salons originally started as low-key gatherings of friends, they eventually “included Salvador Dali, Carl Van Vechten, William Carlos Williams, John Huston, and Virgil Thomson”. Modeled after the weekly salons that Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas hosted in Paris, which Henri-Ford had attended in the early 1930s, these salons became legendary, so much so that in her memoir Just Kids Patti Smith would lament that by the time she attended the salon in the 1970s, it had lost the luster that made her so excited to attend in the first place. Faulkner had the luxury of attending the salon in its prime. There he would have met Henri-Ford, the young pioneer of surrealism whose first novel, written with his homosexual friend Parker Tyler, stands as one of the original novels of the gay genre in American literature, The Young and the Evil (1933). The reputation of that novel would precede it, having been praised by no less than Djuna Barnes and Gertrude Stein.

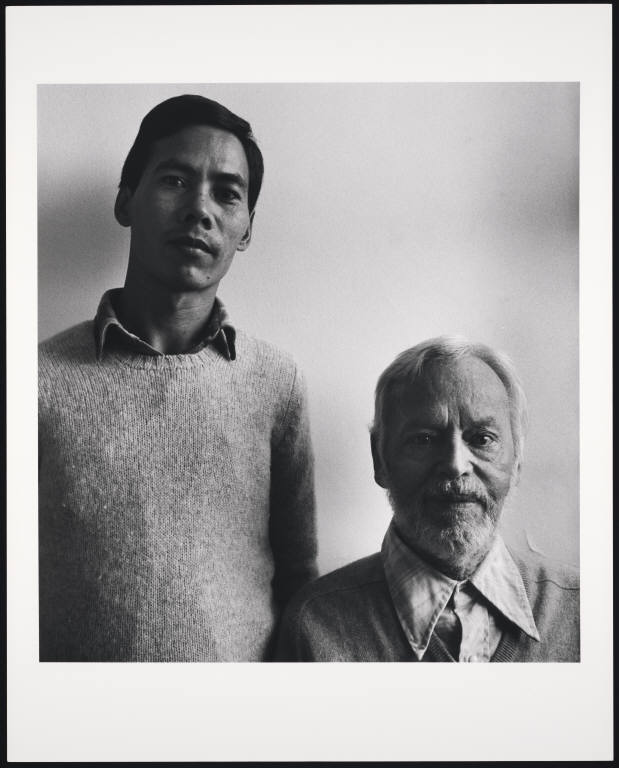

Andrea Tagliabue was an Italian actor who had a romantic relationship with the artist and writer Charles Henry Ford. The pair lived together in Paris and New York for periods of time around 1960. The photographs by Cecil Beaton and Herbert List offer intimate, relaxed portraits of 'Renzo,' as Ford affectionately nicknamed Tagliabue.

In 1962 Ford returned to the United States and began associating with Pop artists and underground filmmakers. He met Andy Warhol in 1962 at a party at his sister's and an interview recounting his association with Warhol is featured in the book ''The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol''. In 1965, Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York hosted an exhibition of his work called "Poem Posters", lithographs with "acid colors, spliced-together typefaces and pop culture images" he had made on an offset lithographic press in Athens in 1964-65. They were "a particularly visual and outrageous form of concrete poetry" in which Ford exploited all he had learned of publishing, graphic design, and printing.

In the late 1960s he began directing his own films. The first was ''Poem Posters'' (1967), a 20-minute documentary about the installation, opening, and breakdown of the exhibition of his surrealist collages. It was chosen for the Fourth International Avant-Garde Festival in Belgium.[16] His second film was ''Johnny Minotaur'', which premiered in 1971. Its nominal subject was the Greek myth of Theseus, Ariadne, and the Minotaur's labyrinth. It was an exercise in surrealist juxtaposition of styles, including cinema vérité and "erotic kitsch". Shot in Crete and employing the structure of a film-within-a-film, it pretended to document the experiences of a film producer as he worked on a contemporary film about a classical myth, but Ford's work moved freely between the documentary subject and the supposed film in production with little respect for any distinction between the two.[17] A reviewer in the ''New York Times'' said of the film, "The order of the day is male anatomy and male sexuality."[18] The film played for a time at New York's Bleecker Street Cinema and been rarely screened since then. The Film-Makers' Cooperative has screened what it describes as the only surviving print of the film in festival settings, though some venues have refused to show it because of its explicit sexual content given the youthful appearance of some of the actors.[19]

In the 1970s Ford moved to Nepal and bought a house in Katmandu. In 1973 he hired a local teenager, Indra Tamang, to run errands and cook, then taught him photography and made him his assistant. Tanang remained at his side for the rest of Ford's life, "a sort of surrogate son", artistic collaborator, and personal caretaker. Together they toured from Turkey to India, relocated to Paris and Crete, and then to New York City.[20] Tanang was born about 1953. He left a wife and two daughters in Nepal. He was widowed in 1986, remarried in the 1990s, had another daughter, and brought his two elder daughters to the U.S. Ford and later his sister Ruth Ford paid Tanang so little his wife needed to work to support the family. Ford compiled a number of art projects using his collage materials and Tamang's photography.

In 1992, he edited an anthology of articles that had appeared in ''View''. Titled ''View: Parade of the Avant Garde, 1940-1947'', it carried an introduction by Paul Bowles.[21] [22]

In 2001, he published a selection from his diaries as ''Water From a Bucket: A Diary 1948-1957''. Covering the years from his father's final illness to the death of Tchelitchew, it provided, according to ''Publishers Weekly'', "richly observed details, both quotidian and unusual, constituting a delightful, moving, poetic portrait of a man and a subculture".[23]

Also in 2001, he was the subject of a two-hour documentary film, ''Sleep in a Nest of Flames'', directed by James Dowell and John Kolomvakis.[24]

When Tchelitchew died in Rome in 1957, the ''New York Times'' described Ford as his "life-long companion and secretary.[25]

Ford and his sister had separate apartments at The Dakota apartment building in their final years, where Tanang served as their caretaker.

Charles Henri Ford died, aged 94, on September 27, 2002, in New York City.[26] He was survived by his younger sister, actress Ruth Ford, who died in 2009, aged 98.[27]

Ford left some paintings and the rights to his co-authored novel ''The Young and Evil'' to Tamang, who took the ashes of both Fords to Mississippi for burial in 2011. The inscription on the gravestone of Charles Henri Ford reads "Sleeping Through His Reward". While serving the Fords, Tamang lived with his wife and three daughters in a small house in Queens. Ruth Ford willed him two apartments in the Dakota and a collection of Russian surrealist art while disinheriting her own daughter and two grandchildren.[28] [29]

My published books: