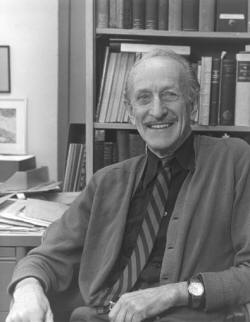

Partner Harry Dwight Dillon Ripley

Queer Places:

Trewyn House, Abergavenny NP7 7PF, UK

Saltmarshe Castle Park, Stourport Road, Bromyard HR7 4PN

Lower Brockhampton House, Grooms Brockhampton Mews, Bringsty, Worcester WR6 5TB, UK

Wilcroft House, Bartestree, Hereford HR1 4BD, UK

Harrow School, 5 High St, Harrow, Harrow on the Hill HA1 3HP

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Crelash aka The Spinney, Spinney Lane, Little London, Heathfield, East Sussex TN21 0NU, UK

330 N Bristol Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90049

The Padre Hotel, 1955 N Cahuenga Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90068

Hotel Carmel - Santa Monica Hotel, 201 Broadway, Santa Monica, CA 90401

9921 Robbins Dr, Beverly Hills, CA 90212

147 S Spalding Dr, Beverly Hills, CA 90212

Wappingers Falls,

Noxon Rd, Lagrangeville, NY 12540

416 E 58th St, New York, NY 10022

Stirling House, 3135 Main Rd, Greenport West, NY 11944

New York Botanical Garden, 2900 Southern Blvd, Bronx, NY 10458

Smith Hill Cemetery,

Honesdale, Wayne County, Pennsylvania, USA

Rupert

Charles Barneby (October 6, 1911 – December 5, 2000) was a widely-honored self-taught botanist. According to the New York Botanical

Garden, Barneby "has been acclaimed one of the world's leading plant taxonomists, ranked by many

with the legendary nineteenth-century taxonomist George Bentham." He named 1,160 plant species

new to science. He had at least 25 different species named after him, as well as genera of plants

named in his honor—Barnebya, Barnebyella, Barnebydendron and Rupertia. His Atlas of North

American Astragalus (New York Botanical Garden, 1964) took twenty years to complete. The book is

1188 pages, includes 552 taxa and is still considered the field's standard text.

Rupert

Charles Barneby (October 6, 1911 – December 5, 2000) was a widely-honored self-taught botanist. According to the New York Botanical

Garden, Barneby "has been acclaimed one of the world's leading plant taxonomists, ranked by many

with the legendary nineteenth-century taxonomist George Bentham." He named 1,160 plant species

new to science. He had at least 25 different species named after him, as well as genera of plants

named in his honor—Barnebya, Barnebyella, Barnebydendron and Rupertia. His Atlas of North

American Astragalus (New York Botanical Garden, 1964) took twenty years to complete. The book is

1188 pages, includes 552 taxa and is still considered the field's standard text.

Barneby was curator emeritus of the New York Botanical Garden's Institute of Systematic Botany, and was considered one of the world's top experts on beans. He had three genera (groups of species sharing common characteristics, like roses or oaks) of plants -- Barnebya, Barnebyella, and Barnebydendron -- and 25 species named after him.

''I doubt that anyone has found more bona fide species of flowering plants in the continental United States since the halcyon days of the last century, when it seemed that almost everything was new,'' William Cronquist, senior scientist at the garden, which is in the Bronx, wrote in 1981.

Barneby's specialty, taxonomy, the science of classifying organisms into related groups, had seemed to be receding in importance as botanic research increasingly concentrated on molecular biology. But Brian Boom, vice president for botanic science at the garden, said the exact definitions that taxonomy provides were rapidly becoming the basis for the most sophisticated genetic research.

Rupert and Dwight at Harrow

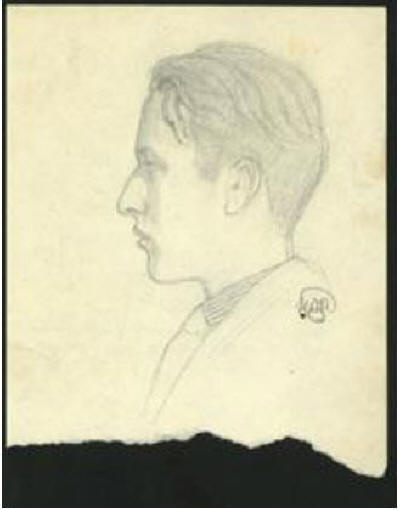

Dwight Ripley. Pencil sketch of Master Rupert Barneby at

Harrow, 1925. In frame.

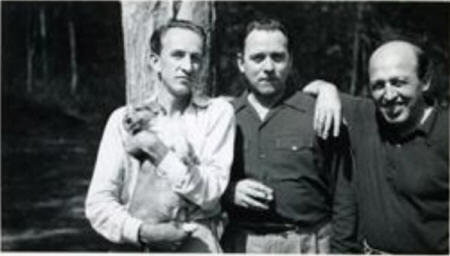

Rupert Barneby (holding Possum), Dwight

Ripley, and Clement Greenberg at Dwight and

Rupert's home at Wappingers Falls, 1951.

Rupert by Dwight Ripley

For example, to study which genes prompt resistance to drought, researchers might begin by choosing from the thousands of desert plants Barneby had collected and stored in vast rooms of drawers.

''The molecular biologists are asking us, 'What are the most interesting questions to pursue?' '' Dr. Boom said.

Barneby's colorful, quirky personality also made an enduring mark. He lived for years over a stable in the botanic garden, was friends with literary luminaries like W. H. Auden and Aldous Huxley and created magnificent rock gardens with more than 1,000 plant species. He and his partner for 48 years, Harry Dwight Dillon Ripley, who died in 1973, were friends and early patrons of Jackson Pollock and others in the New York School of Abstract Expressionist painters.

His dry wit was famous. In an interview in the ''About New York'' column in The New York Times in 1992 he said of having no formal education in botany: ''I'm an autodidact, but that doesn't mean I don't know.'' Of beans, he said: ''They choose you. I don't think I chose them.''

Many of his discoveries were desert plants growing in very circumscribed areas. He found the sentry milk-vetch in a stand of only 100 plants on the south rim of the Grand Canyon and the gumbo milk-vetch in the hoof prints left by passing cattle on gumbo flats near Kanab, Utah.

James Grimes, senior botanist at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne, Australia, said of Barneby's output of more than 6,500 pages of papers, monographs and journals, ''He has perhaps published more pages of monographic and floristic treatments than any other botanist of the 20th century.''

Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden, said, ''Rupert Barneby was a great student of plants in the style of George Bentham and the other encyclopedic workers of the 19th century, who would tirelessly analyze all we knew about enormous groups of plants and reduce that knowledge to lucid prose.''

Rupert Charles Barneby was born on Oct. 6, 1911, at Trewyn, a 17th-century country house at the edge of the Brecon Beacons and almost directly on the border between England and Wales. He was the son of Philip Bartholomew Barneby (born 1875) and Louisa Geraldine Ingham. Philip was the son of William Barneby of Saltmarshe Castle, Worcs. William inherited the castle from his uncle, Edmund Barneby. As a child, Rupert marveled at insects, plants and fossils, and two aunts encouraged his interests by giving him books on them. He was a member of a young naturalists' club.

He went to Harrow, where at 14 he met Ripley, who was two years older and knew the Latin names for plants, a facility that greatly impressed Barneby. Barneby was always delighted to tell of how scandalized officials of the exclusive boarding school were by the boys' relationship -- not because such a schoolboy romance was unusual, but because Ripley was an American.

Barneby went to Cambridge and Ripley to Oxford. While still at university, the two went on joint plant-hunting trips to Spain and northern Africa. They brought back specimens to plant at Ripley's estate in Sussex. Their rock garden there included 1,138 species, many of which were so rare they were eventually given to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. During Dwight's final year at Oxford, in 1931, the prestigious firm of Elkin Mathews & Marrot published Dwight's collection of 31 poems, called simply Poems, dedicated to "Ruperto Barneby, poetae dilectissumo (the poet's most beloved)." At Oxford, Dwight’s chum was Harold Chown, whose father was French and whose girlfriend, soon to be wife, Hope Manchester, was American. Among Dwight’s chums from the Evelyn Waugh’s generation were Cyril Connolly, distantly Irish and married to an American, Jean Connolly, and Brian Howard, who was raised British but whose parents were American and whose father, moreover, had changed the family name.

Jean Connolly, unfretufully American, was born Jean Bakewell to a wealthy family (Bakewell glass) in Pittsburgh in 1910, arrived in Paris when she was eighteen, and met Cyril Connolly there the next year. On their honeymoon in Mallorca in 1930 the Connollys became friends with Tony Bower. He too was American; his mother was a friend of Dwight Ripley's grandmother in Connecticut, but he had lived in England since he was six, and Dwight knew him from childhood. Bower also attended Oxford, and it was he who introduced Jean to Rupert and Dwight.

Jean Connolly moved in an entourage of young male couples that included Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby, Tony Bower and Cuthbert Worsley, Peter Watson and Denham Fouts, Brian Howard and Toni Altmann. "Drink, night life, tarts and Tonys," complained Cyril Connolly, who referred to the whole entourage as "Pansyhalla." They liked Picasso, Marcel Proust, and Francis Poulenc, favored in architecture the Baroque, admired Josephine Baker and jazz. Someone took a copy of Dwight Ripley's Poems to Jean Cocteau, who responded "Quel néurophate!", a diagnosis that Rupert relayed with wicked relish. When Gerald Heard published two books in 1931 to propose that evolution demanded an evolved human consciousness, Brian Howard called them "the most important that have ever been written since the Ice Age." In Pansyhalla, a compelling example was set by Peter Watson, who joined with Cyril Connolly in 1939 to found Horizon and then financed that influential journal thoughout its career. Until the WWII, Watson lived mostly in Paris; a portrait of Jean Connolly, by Man Ray, was in his apartment. In 1938 he subsized the publication of a first book of poems by Charles Henri Ford, the young poet who was painter Pavel Tchelitchew's lover, and who, back in New York by 1940, would found a counterpart to Horizon, the trendier but likewise influential magazine View. It was View that brought John Bernard Myers from Buffalo to be its managing editor, and Myers who, as director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery that Dwight himself sponsored, acted as impresario for a cast of painters and poets that seems now, to typify the postwar New York scene.

At Cambridge, while Dwight Ripley was sending him photos from Antibes, Rupert Barneby was having an affair with a German journalist, twenty-two years his senior, whose name was Jakob Altmaier. A prominent social democrat, Altmaier had been editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung. Berlin correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, and foreign correspondent for an association of social democratic presses. He worked out of Belgrade, then Paris, where he met Dwight, and finally London, where he fell in love with Rupert. It would appear that his journalism was effective, because he incurred the displeasure of the British government, which wanted him out of England, or of the German government, which wanted him discredited, or maybe both. Whatever the motives, they were sufficient in 1932 for British police to enter Rupert's rooms and locate, without much difficulty, the letters from Altmaier that Rupert had never imagined he had to hide. Rupert was sent down (briefly, it must have been, since he took his degree that same year), but Altmaier was deported to Germany and Rupert never heard from him again. Almaier was Jewish, a socialist, and caught having an affair with a younger man; he was not likely to survive the National Socialist regime. Rupert believed, for the rest of his life, that he had been used by his own country to murder someone he loved. Christopher Isherwood wrote that when England rejected Heinz Neddermeyer it became for him, in that instant, "the land of the Others." Rupert's response was private but quite as intense. He never saved letters again. Almaier acually survived. With the rise of the Nazi party in 1933, he fled to Paris. After the outbreak of war, he went to the Balkans, Spain, and finally to northern Africa, where was associated with British forces. Until 1948, he was a correspondent for two social-democratic newspapers. Altmaier lost over 20 relatives during the Holocaust. In 1949, Altmaier returned to Germany. He was a member of the post-World War II Bundestag from its inception in 1949 until his death, as the Hanau representative. He was intimately involved with the 1952 reparation treaty between West Germany and Israel. Altmaier was also a member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe from 1950 until his death.

Barneby's father refused to let him study botany, because he thought it was unsuitable for a young man to devote himself to flowers. His father found only three careers acceptable: the army, the navy or the church. ''I was always unsuited for the army or navy and I hated the church,'' Barneby said. ''That's really why I came to America.'' Rupert completed his own curriculum at Cambridge in 1932 and persuaded his father to send him to the university at Grenoble, in France, for further training in languages. He did not explain to his father that Dwight was already there. When Rupert returned to England, Philip Barneby would not meet his son at the Spinney, Dwight's house, not would he allow him home. He summoned him to Hyde Park instead. Relinquish the attachment, he said, and come home as before. Otherwise never return. Rupert never saw his father again.

At the Spinney, Dwight meant to create for Rupert and himself a secure venue for enjoying the avant-garde. Rupert remembered keenly the day in 1932, he was still twenty, Dwight was twenty-three, when they went to the Alex Reid & Lefevre Gallery, on King Street in London, to buy their first painting. Dwight had picked Parrots in a Cage, painted in 1927 by Christopher Wood, an artist who, long with Paul Nash, is sometimes credited with bringing the flat forms and bold colors of modern European art to English painting.

Dwight Ripley kept a residence in London, and with his partner Rupert Barneby mixed in circles that included Dwight's fellow Oxonians W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender, as well as Christopher Isherwood, the Huxleys, the Sitwells, Cyril Connolly and his American wife, Jean Connolly: circles in which the admired standards were for satire in literature and, in society, sarcasm and wit. Jean Connolly, who became one of Dwight's closer friends, was at the center of avant-garde sets on both sides of the Atlantic; she was the only woman, said Auden, who could keep him up all night. At a party in 1935 at Richard Wyndham's house, the Tickerage (Wyndham was a soldier, writer, and photographer who was killed covering the Arab-Israeli was in 1948), the guests were Dwight Ripley and Jean Connolly, Patrick Balfour (later Lord Kinross), Constant Lambert (the composer), Angela Culme-Seymour (who was to marry Balfour), Tom Driberg (the columnist "William Hickey" at the Daily Express and later member of Parliament), Cyril Connolly, Stephen Spender, Tony Hyndman (Spender's boyfriend), Mamaine Paget (later the second wife of Arthur Koestler), John Rayner (also of the Daily Express), and Joan Eyres-Monsell (later Leigh-Fermor).

When the impending civil war made it impossible to collect in their beloved Spain, Rupert and Dwight decided on a substitute destination where the language was also Spanish and the condistions semiarid: Mexico. They arrived in 1936 in Los Angeles and readied themselves for an expedition south.

On board ship from Marseilles to Cairo in 1937 they met Peter Markham Scott, artist, later founder of the Slimbridge Refuge and cofounder of the Word Wildlife Fund, fresh then from a bronze-medal performance as a single yachtsman in the Olympics. Scott made a penil sketch of Rupert. The sketch, which surfaced years later in Rupert's loft, is of a sulky, eye-catching 26-year-old.

In 1938 they were back in California. This time the live plants they collected were established temporarily in a holding garden at 330 North Bristol, the imposing Spanish-style residence they rented in the Brentwood setion of Los Angeles. From 330 they mounted expeditions eastward to Death Valley and Titus Canyon, hoping to find the unusual, yellow-flowered Maurandya petrophila.

Barneby, who had been disinherited, and Ripley, whose personal fortune always paid the bills, headed straight to Hollywood, where they were quickly disillusioned by seeing Clark Gable without pads on his shoulders and torso. ''He was a little shrimp of a man,'' Barneby lamented. From their house at #330, Barneby discovered they could look down with binoculars on neighbour Cary Grant. Noël Coward’s staying with our Cary, a ce qu’il parait, so that’s one question settled, he announced. When Rupert by chance shared a train ride with Gary Cooper, and found him talkative, it was Dwight who was the most delighted. Contacting the Cooper must have been quite a thrill, he ventured. Wouldn’t the over-wrought little pansies back in Blighty be jealous if they knew?

W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood had left England in January 1939. Auden stayed in New York, but Isherwood went on to Los Angeles, where he joined Dwight's still closer friends, Christopher Wood and Gerald Heard, who had emigrated along with Aldous Huxley, Maria Nys, and son Matthew Huxley two years before. Rupert obtained a new passport in June, and by October 1939 the two men were in New York.

In late 1939, Rupert Barneby and Dwight Ripley lived at Padre Hotel, Hollywood, and they became part of the wartime colony of English expatriates that soon flourished along the southern California coast. At the beginning of WWII, Jean Connolly moved to Los Angeles and brought her close friend, Denham Fouts, a storied young American who was the lover then of Peter Watson, the wealthy publisher of Horizon, and was widely assumed to have been, before that, the lover of Prince Paul of Greece. These are the figures satirized by Christopher Isherwood in his novel Down There on a Visit, a novel in which the portrayal of Jean Connolly as Ruthie is so rude that it confirmed, said Rupert Barneby, Dwight Ripley's longstanding opinion that Isherwood was a snit. Soon the circle of expatriate friends around Dwight and Rupert had expanded to include several who found work, as did Isherwood, in the motion-picture industry. Especially close to Dwight were Keith Winter, a novelist, playwright, and Oxford classmate who worked as a screenwriter on Joan Crawford movies (he wrote the screenplay for Above Suspicion), and Richard Kitchin, a set artist who painted a Surrealist portrait of Dwight.

In December 1941 Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby moved from the Santa Monica Hotel to a more satisfactorily residential address, 9921 Robbins Drive in Beverly Hills, and invited to dinner Miss Dicky Bonaparte, an immigration counselor was was skilled at getting alien actors and actresses into the country, and who had arranged earlier a legal arrival for Christopher Isherwood. This is how they obtained a legal entry in the United States for Barneby.

Early in 1942, Barneby and Ripley went to New York, joining their friend Jean Connolly, who had moved east and could introduce them immediately to the art world that Rupert like to call "Upper Bohemia." Jean's current lover, only somewhat to the chagrin of her likewise active husband back in England, was Clement Greenberg, the critic who would help make Jackson Pollock famous. Greenberg, writing to his friend Harold Lazarus described the new arrivals: "Dwight Ripley, a millionaire and rather masculine... and his pal, Rupert Barneby. They are both botanist and English," reported Greenberg, "and Dwight is in addition a philologist, expert in the Latin languages and Russian. Something new." In August the two men took a one-year lease at 147 South Spalding Drive in Beverly Hills. By the time the lease was ready to expire, they had bought an old farmhouse and its surrounding hundred acres on Noxon Road in the town of LaGrange, Dutchess County, New York. This was 20 miles from Jean Connolly's house in neighboring Connecticut. Dwight arrived first, July 24, 1943. On a shape outcrop behind the farmhouse they started a rock garden.

The two continued plant-hunting in the American West. The first plant Barneby named was a parsley-like umbellifer found on Yucca Flat in Nevada, said Douglas Crase, who is researching a book on Ripley. Barneby labeled it Cymopterus ripleyi. The two went on to build magnificent rock gardens at homes in the New York region, where they moved in 1943.

Jean Connolly by this time had dropped Greenberg and was involved with Laurence Vail, the Surrealist artist and former husband of Peggy Guggenheim, heiress, angel of expatriate European artists, and owner of Art of This Century Gallery. With bohemian aplomb, however, it was the two women who began living together in Guggenheim's duplex at East 61st Street, New York. Thank to this arrangement, Rupert and Dwight found themselves frequently in New York at the center of Upper Bohemia. "Jean Connolly, Dwight Ripley, Matta, Marcel Duchamp were around a great deal," recalled Lee Krasner, the painter who was Jackson Pollock's wife. "They were at all the parties." Rupert and Dwight were at the now famous party during which Pollock's Mural was first shown and Pollock relieved himself in the fireplace. Barneby remembered Marcel Duchamp, the avatar of cool in the art world today, as a "pompous pundit." He recalled Guggenheim herself as "mean"; she "dressed like a hag," her stagy consersational asides were "like a dagger in the heart."

In 1945 Willard Maas published a poetry anthology, The War Poets. The love sonnet Letter to R, written by Maas while an army private at Camp Crowder, MO, was intended for Rupert Barneby. Maas was to become an influential avant-garde filmmaker after the war, and Dwight Ripley would help finance his projects. For his part, Dwight soon was having an affair with Peggy Guggenheim, who admired his English accent, his youth (he was ten years younger), and his indifference to her wealth. She liked to introduce him as her fiancé. "She fell abruptly out of love with Dwight," said Rupert. "He was staying at her house at East 61st and she'd gone out to some party, and Dwight came back in a cab with a very handsome driver, and Peggy found them in bed together."

The decision to remain in the United States had become inevitable, and by November 1951, when W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood arrived to spend a nostalgic weekend with Rupert and Dwight at Wappingers Falls, it was irrevocable too. England, for all four, was the place they had left behind. The rare species cultivated at the Spinney, Waldron, Sussex, were auctioned earlier that spring. The Spinney itself passed to a new owner, the solicitor who all these years had managed Dwight's interests under the terms of his father's will.

Barneby, eager to turn over a new leaf, showed up in the early 1950's at the botanical garden in the Bronx. He brought hundreds of plant specimens, which fascinated resident scientists. In essence, he began hanging around and doing things, including serving tea at 4 P.M. daily. Ted Barkley, who was a student at the garden in 1957, remembered Rupert from these days, when he drove down to the Bronx from Wappingers Falls bringing his Sheltie, whose name was Possum. "Rupert had a little dog that was his close companion," recalled Barkley, "and after lunch he would go to his car and let out the dog, then for a quarter hour or so, the two would run together across the great open lawns in front of the Musuem Building. It was interesting, to say the least, to see this very thin and politely reserved man running full tilt across the lawns, with a little dog."

In 1957 the experimental filmmaker Marie Menken was so fascinated with the rock garden at Wappingers Falls, that she filmed a five-minute, 16mm film, Glimpse of the Garden, described by Stan Brakhage as "one of the toughest" of her influential works. Menken was the wife of Willard Maas, the soldier poet once enamored of Rupert.

For a few years beginning in 1957 the two men rented an apartment at 416 East 58th Street, near Sutton Place, in New York. The young Gore Vidal collected the rent. In the city, Dwight seemed only to drink more heavily. When he tried simply to stop, the effects of the withdrawal landed him in Vassar Hospital. Shaken, he resolved on sobriety, and together he and Rupert decided to move to a house they had found for sale in Greenport, Long Island, not far from their painter friends Theodoros Stamos, Lee Krasner, and Alfonso Ossorio. They arrived in October 1959, eager to renovate the decaying Greek Revival mansion that stood at 3135 North Road on the east edge of town. To Tom Howell, Dwight wrote that he was "now happily esconced in a divine house which, along with its new owner, has been saved in the nick of time from Crumbling into Ruins."

Ripley's extensive manuscript held in the archives of the NYBG, the Etymological Dictionary of Vernacular Plant Names, was nearing completion at the time of Ripley’s death on December 17, 1973. The year after his death, Barneby paid tribute to their collecting life together by arranging for the editor and gallerist John Bernard Myers to publish Ripley's botanical journals in his obscure but influential art journal Parenthèse. In 1974, Ripley and Barneby were honored with the American Rock Garden Society’s Marcel Le Piniec Award for their plant explorations and introduction of new rock garden species.

Frank Polach first met Rupert Barneby in 1975 at The New York Botanical Garden. The two shared an interest not only in botany, but also art and poetry. Both Douglas Crase and Frank soon became close friends with Rupert.

In 1989, Barneby was named curator of systematic botany, the first and last paying job he ever had. He worked every day until this July, when he could no longer open his seemingly endless drawers of legumes. The NYBG allowed him to live in the loft above the Old Stone Stable of the Lorillard Estate.

But he was always far more than a bean counter anyway, as suggested by his wistful recollection at once spotting Greta Garbo walking in the rain in Manhattan. In his own way, he had much in common with the famous loner, suggested his longtime friend, Budd Myers, a writer and editor.

''He really didn't like many people, simply because he didn't find them very interesting,'' he said. He had no survivors, said Mary Tobin, a spokeswoman for the garden.

Barneby was unimpressed by the many honors he received, including the Millennium Botany Award, presented to him by the International Botanical Congress in 1999.

''I'm conscious of the prestige of the medallion,'' he said, ''but hideously aware that it's an award for survival rather than for merit. It's part of the dismal cult of personality that started in Hollywood and now has infected the entire planet.''

Rupert moved from his unforgettable loft at the Botanical Garden on January 12, 1998. He had arranged to live at Kittay House, 2550 Webb Avenue in the Bronx, because it was only minutes from the NY Botanical Garden. Douglas and Frank helped move Rupert from his New York Botanical Garden loft into an assisted living home. They shipped many of Rupert and his late partner Dwight Ripley's items to their Carley Brook home in Pennsylvania. Crase began reading Ripley's diaries and found that they illuminated Ripley's extensive role in the postwar art world and his part in the creation of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Rupert Barneby died on December 5, 2000, at The New Jewish Home, Kittay Senior Apartments in the Bronx. He was 89.

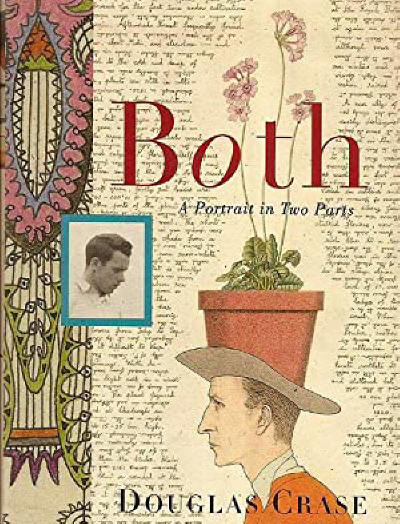

Rupert Barneby left many of his belongings to Frank Polach, who was also the executor of his estate. In 2004, Douglas Crase published Both: A Portrait in Two Parts, a dual biography of botanist Rupert Barneby and artist Dwight Ripley, that incorporated much of the material that had been willed to Frank Polach.

My published books: