Queer Places:

Bryn Mawr College (Seven Sisters), 101 N Merion Ave, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010

260 Cumberland St, Brooklyn, NY 11205

14 St Luke’s Place, New York, NY

35 W 9th St, New York, NY 10011

37 Charlton St, New York, NY 10014

Evergreen Cemetery, 799 Baltimore St, Gettysburg, PA 17325

The Rosenbach Museum & Library, 2008 Delancey Pl, Philadelphia, PA 19103

Marianne

Craig Moore (November 15, 1887 – February 5, 1972) was an American

modernist poet, critic,

translator, and editor. Her poetry is noted for formal innovation, precise

diction,

irony, and wit.

Marianne

Craig Moore (November 15, 1887 – February 5, 1972) was an American

modernist poet, critic,

translator, and editor. Her poetry is noted for formal innovation, precise

diction,

irony, and wit.

Margaret "Peggy" James Porter deferred marriage until relatively late (her 30th year), and then chose as a husband a man 22 years older than herself: Bruce Porter of San Francisco, who, years before, had been one of her uncle, Henry James' beloved younger men and whose sexual preferences were decidedly ambivalent. It is known that during her years at Bryn Mawr (1908-1910), Peggy had formed an intensely homosocial attachment to the poet Marianne Moore.

Moore's first professionally published poems appeared in The Egoist and Poetry in the spring of 1915. Harriet Monroe, the editor of the latter, would describe them in her biography as possessing "an elliptically musical profundity".[6]

In 1916, Moore moved with her mother to Chatham, New Jersey, a community with commuting transportation to Manhattan. Two years later, the two moved to New York City's Greenwich Village, where Moore socialized with many avant-garde artists, especially those associated with Others magazine. The innovative poems she was writing at that time received high praise from Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, H.D., T. S. Eliot, and later, Wallace Stevens.

At the end of the 1910s, the two most talked about and arguably the most influential poets in New York were Marianne Moore and Mina Loy. Moore's first book, Poems, was published without her permission in 1921 by the Imagist poet H.D. and H.D.'s partner, the British novelist Bryher.[4][7] Moore's later poetry shows some influence from the Imagists' principles.[8]

Her second book, Observations, won the Dial Award in 1924. She worked part-time as a librarian during these years; then from 1925 to 1929, she edited The Dial magazine, a literary and cultural journal. This position in the literary and arts community extended her influence as an arbiter of modernist taste; much later, she encouraged promising young poets, including Elizabeth Bishop, Allen Ginsberg, John Ashbery, and James Merrill. When The Dial ceased publication in 1929, she moved to 260 Cumberland Street[9] in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn, where she remained for thirty-six years. She continued to write while caring for her ailing mother, who died in 1947. For nine years before and after her mother’s death, Moore translated the Fables of LaFontaine.

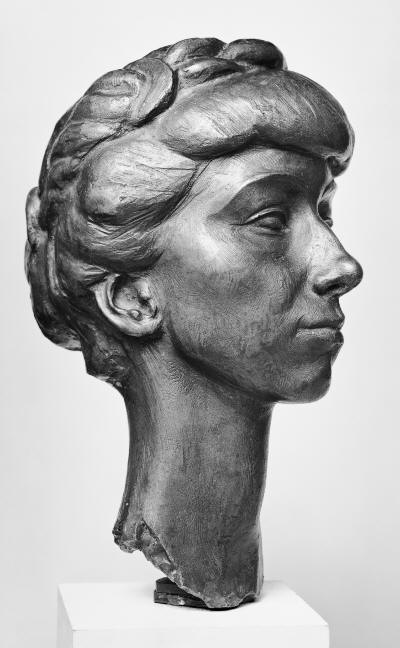

Marianne Moore, by Gaston Lachaise, Metropolitan Museum of Art

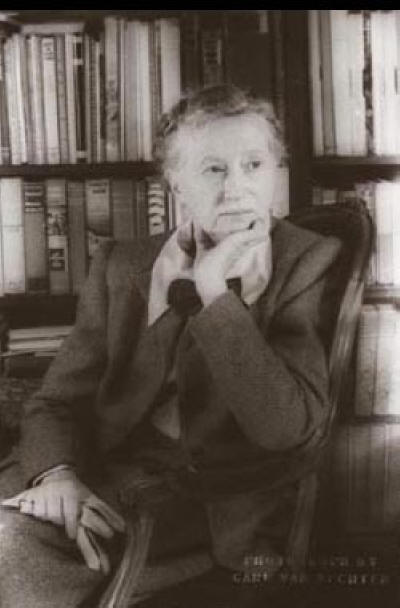

by George

Platt Lynes

14 St Luke’s Place

35 W 9th St

In 1933, Moore was awarded the Helen Haire Levinson Prize by Poetry magazine. In 1951, her Collected Poems won the National Book Award,[10] the Pulitzer Prize, and the Bollingen Prize. In the book's introduction, T. S. Eliot wrote, "My conviction has remained unchanged for the last 14 years that Miss Moore's poems form part of the small body of durable poetry written in our time."[3] After years of seclusion, she emerged as a celebrity, speaking at college campuses across the country and appearing in photographic essays in Life and Look magazines. Moore became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1955.[3] She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1962.[11] Moore continued to publish poems in various magazines, including, The Nation, The New Republic, Partisan Review, and The New Yorker, as well as publishing various books and collections of her poetry and criticism.

She moved to 35 West Ninth Street in Manhattan in 1965. After she moved back to Greenwich Village, she was widely recognized around town for her tricorn hat and black cape. She liked athletics and was a great admirer of Muhammad Ali, for whose spoken-word album I Am the Greatest! she wrote the liner notes. She became known as a baseball fan, first of the Brooklyn Dodgers and then of the New York Yankees. She threw out the ball to open the season at Yankee Stadium in 1968.

Moore suffered a series of strokes in her last years. She died in 1972, and her ashes were interred with those of her mother at the family's burial plot at the Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[12][13] Louise Crane was the executor of Moore's estate. By the time of her death, Moore had received many honorary degrees and virtually every honor available to an American poet. The New York Times printed a full-page obituary.[14] In 1996, she was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[15]

Moore corresponded with Ezra Pound from 1918, and visited him regularly during his incarceration at St. Elizabeth's. She opposed Benito Mussolini and Fascism from the start, and objected to Pound's antisemitism. Moore was a Republican and supported Herbert Hoover in 1928 and 1932.[16][17][18] She was a lifelong ally and friend of the American poet Wallace Stevens, as demonstrated in her review of Stevens's first collection, Harmonium, and, in particular, by her comment about the influence of Henri Rousseau on the poem "Floral Decorations for Bananas". She also corresponded, from 1943 to 1961, with the reclusive collage artist Joseph Cornell, whose methods of collecting and appropriation were much like her own.[19]

In 1955, Moore was invited informally by David Wallace, manager of marketing research for Ford's "E-car" project, and his co-worker Bob Young, to suggest a name for the car. Wallace's rationale was "Who better to understand the nature of words than a poet?" On October 1955, Moore was approached to submit "inspirational names" for the E-car, and on November 7, she offered her list of names, which included such notables as "Resilient Bullet", "Ford Silver Sword", "Mongoose Civique", "Varsity Stroke", "Pastelogram", and "Andante con Moto". On December 8, she submitted her last and most famous name, "Utopian Turtletop". The E-car was christened by Ford as the Edsel.[20]

Moore never married. Her living room has been preserved in its original layout in the collections of the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia.[21] Her entire library, knick-knacks (including a baseball signed by Mickey Mantle), all of her correspondence, photographs, and poetry drafts are available for public viewing.

Like Robert Lowell, Moore revised many of her early poems in later life. Most of these revised works appeared in the Complete Poems of 1967. Facsimile editions of the theretofore out-of-print 1924 Observations became available in 2002. Since that time, there has been no critical consensus about which versions are authoritative. As Moore wrote, as a one-line epigraph to Complete Poems, which offered her well-known work "Poetry" cut down from twenty-nine lines to three: "Omissions are not accidents."[22][23][24] In a foreword to A Marianne Moore Reader in 1961, Moore said her favorite poem was the Book of Job.[25]

Moore's novel and an unfinished memoir have not been published.[25] In her will, she established a fund for the support of the Camperdown Elm in Brooklyn's Prospect Park, a rare and ancient tree that she had celebrated in a poem.[26]

In 2012, she was inducted into the New York State Writers Hall of Fame.

Moore is also connected with Elinor Wylie.

My published books: