Queer Places:

Eton College, Windsor SL4 6DW, Regno Unito

Hawtreys, Tottenham House, Marlborough SN8 3BE, Regno Unito

Hawtreys, Newbury Road, Thatcham RG19 8LD, Regno Unito

Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, Gower St, Bloomsbury, London WC1E 6BT, Regno Unito

17-19 Pelham Pl, South Kensington, London SW7 2NQ, UK

Nymans, Staplefield Lane, Handcross RH17 6EB, Regno Unito

Maddox, Bridgetown, Barbados

The Dorchester, 53 Park Ln, Mayfair, London W1K 1QA, Regno Unito

Les Jolies Eaux, Saint Vincent e Grenadine

Point Lookout, Saint Vincent e Grenadine

Oliver Hilary Sambourne Messel (13 January 1904 – 13 July 1978) was an

English artist and one of the foremost stage designers of the 20th century.

The work of Broadway's gay and lesbian artistic community went on display in

2007 when the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation Gallery presents "StageStruck:

The Magic of Theatre Design." The exhibit was conceived to highlight the

achievements of gay and lesbian designers who work in conjunction with fellow

gay and lesbian playwrights, directors, choreographers and composers. Original

sketches, props, set pieces and models — some from private collections —

represent the work of over 60 designers, including Oliver Messel.

Oliver Hilary Sambourne Messel (13 January 1904 – 13 July 1978) was an

English artist and one of the foremost stage designers of the 20th century.

The work of Broadway's gay and lesbian artistic community went on display in

2007 when the Leslie/Lohman Gay Art Foundation Gallery presents "StageStruck:

The Magic of Theatre Design." The exhibit was conceived to highlight the

achievements of gay and lesbian designers who work in conjunction with fellow

gay and lesbian playwrights, directors, choreographers and composers. Original

sketches, props, set pieces and models — some from private collections —

represent the work of over 60 designers, including Oliver Messel.

Messel is Jewish and was born in London, the second son of Lieutenant-Colonel Leonard Messel and Maud, the only daughter of Linley Sambourne, the eminent illustrator and contributor to Punch magazine. He was educated at Hawtreys, a boarding preparatory school then in Kent, Westminster School and Eton — where his classmates included Harold Acton, Eric Blair and Brian Howard — and at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College.

After completing his studies, he became a portrait painter and commissions for theatre work soon followed, beginning with his designing the masks for a London production of Serge Diaghilev's ballet Zephyr et Flore (1925). Subsequently, he created masks, costumes, and sets – many of which have been preserved by the Theatre Museum, London – for various works staged by C. B. Cochran's revues through the late 1920s and early 1930s. It is at this time that he had a relationship with Peter Watson. His work as a set designer was also featured in the US in such Broadway shows as The Country Wife (1936); The Lady's Not For Burning (1950); Romeo and Juliet (1951); House of Flowers (1954), for which he won the Tony Award; and Rashomon (1959), which was nominated for a Tony Award for his costume as well as his set design. He also designed the costumes for Romeo and Juliet; Rashomon; and Gigi (1973), the latter two receiving Tony Award nominations.

For film his costume designs include The Private Life of Don Juan (1934); Scarlet Pimpernel (1934); Romeo and Juliet (1936); The Thief of Bagdad (1940); and Caesar and Cleopatra (1945). For Romeo and Juliet he also served as Set Decorator. He was Art Director on Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), On Such a Night (1956) and Production Designer on Suddenly Last Summer (1959), for which he was nominated for the Academy Award.

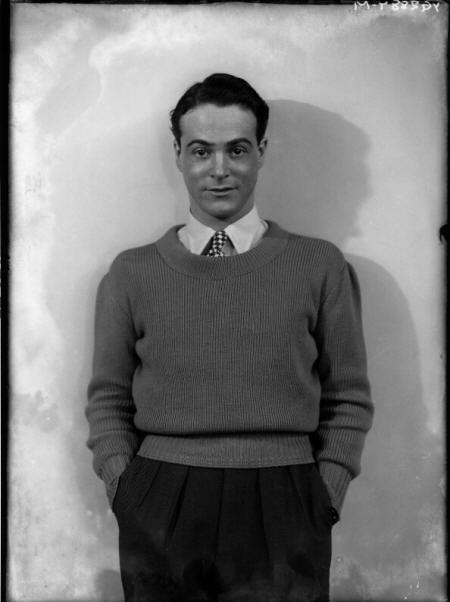

Oliver Messel

by Francis Goodman

2 1/4 inch square film negative, 1945

Bequeathed by the estate of Francis Goodman, 1989

Photographs Collection

NPG x39504

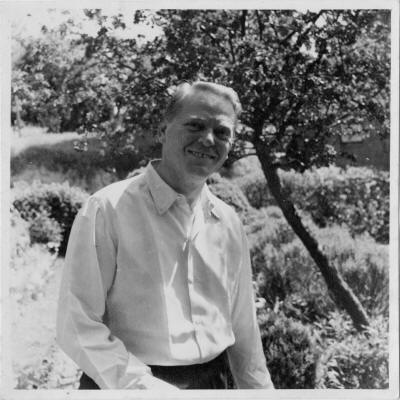

Oliver Messel and Peter Watson

Vagn Riis-Hansen (Oliver's partner), photographer and date unknown, OHM/3/3/12

Considering the work of classic Hollywood's gay directors and gay producers, a small but vital subset of the studio system, suggests "queer cinema" might not be such a modern postulate. Occasionally, a convergence of director, producer, writer, and star came together, such as happened with Camille (1937). The gay writer DeWitt Bodeen said that Camille "represents a meeting of talents that were perfect for its interpretation." In fact, wags like to call the picture a rare "all-gay" studio production, and in some ways it comes close: producer David Lewis, director George Cukor, screenwriter Zoe Akins. Greta Garbo, too, and Mercedes de Acosta had a hand in the early draft of the script before Akins took over. Robert Taylor, who played a stunningly beautiful Armand, was rumored to be having an affair with the film's set decorator, Jack Moore. There was also Adrian on costumes and Sydney Guilaroff doing hair. Rex O'Malley infused his Gaston with a natural feyness, a quality perhaps intended by Cukor and Akins, and another gay actor, Rex Evans, played several bit parts. ("Who is that big man and what part is he playing?" Garbo asked Cukor. "That man is Rex Evans," the director replied, "and he's playing the part of a friend who needs a job.") Cukor also manuevered the hiring of another friend, and another gay man, as the picture's true art director, supplanting the ubiquitous Cedric Gibbons, whose contract nonetheless decreed screen credit. This was Oliver Messel, esteemed scenic and costume designer from the London stage, whose outsider status evoked suspicion in the competitive world of the Hollywood studios. It wasn't Messel's first encounter with the studio bureaucracy; in 1935, during the filming of Romeo and Juliet, Cukor had caused a near war by insisting Messel design the costumes instead of Adrian, whom Cukor, according to several friends, viewed as pompous and pretentious. Cukor, as discreet as he was, never tried to obfuscate either his Jewishness or his gayness in the way Adrian did. "I get annoyed with statements that call George "closeted",", said his longtime friend and Los Angeles Times film critic Kevin Thomas. "George was never closeted. He never pretended to be anything he wasn't. He lived according to the rules of his time, that's all."

During the Second World War Messel served as a camouflage officer, disguising pillboxes in Somerset. According to his fellow officer Julian Trevelyan, he revelled in the opportunity to give his talents free rein. The disguises of his pillboxes included haystacks, castles, ruins, and roadside cafes.[2]

In 1946, Messel designed the sets and costumes for the Royal Ballet's new and highly successful production of Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty, a production which famously starred Margot Fonteyn.[3] It became the first production of the ballet shown on American television, on the program Producers' Showcase. That production, the first ever televised in color, survives on black-and-white kinescope[4] and has been released on DVD.[5] In 2006, it was revived by the Royal Ballet, starring Alina Cojocaru, with some new additions to the scenic design by Peter Farmer, and released on DVD.[6]

Passionate about privacy, Sydney Guilaroff granted a rare interview to the writer John Kobal in the 1950s but refused to be tape-recorded. Unwilling to reveal much about himself, Sydney did prove to be a "fascinating gossip" about other people, calling Cecil Beaton "a swishy little boy" and Oliver Messel "small-minded and nasty."

In 1953, he was commissioned to design the decor for a suite at London's elegant Dorchester Hotel, one in which he would be happy to live himself. The lavishly ornate Oliver Messel Suite, which the hotel advertises as Elizabeth Taylor's favourite place to stay in London, combines baroque and rococo styles with modernist sensibility and a considerable dose of fantasy. The suite, along with other suites that he designed in the Dorchester, are preserved as part of Britain's national heritage. It was restored in the 1980s by many of the original craftsmen, overseen by Messel's nephew, Lord Snowdon (Antony Armstrong-Jones), the former husband of Princess Margaret.

Messel also contributed to retail design, creating the new Delman shoe store for H. & M. Rayne in Old Bond Street in 1960. Whereas upmarket shoe stores had been discreet enclaves dressed with curtains and pot plants, while shoes were consigned to underground stores, this radical refit incorporated display stands and cases, some of them illuminated, to show off hundreds of pairs of shoes. An article in The Observer noted that: "Mr Messel and Mr Rayne are at one in thinking that shoes to buy should be as easy to see and handle as books in a library".[7]

Oliver Messel came from a wealthy, well-connected family, and when his nephew, Antony Armstrong-Jones (Lord Snowdon), married HRH Princess Margaret, a lifelong relationship with the British royalty began. Messel was later to design Les Jolies Eaux, Princess Margaret’s home on Mustique Island in The Grenadines (a 45 min flight west of Barbados), and "Point Lookout" an extraordinary stone beach house on the northern tip of Mustique. In 1959, Messel, exhausted by a demanding theatre season and recurring arthritis, retreated to Barbados and the lush beauty of the eastern Caribbean. He was 55 and at the peak of a career in which he had dazzled three decades of theatre-goers with his fantastic, romantic and inspired stage sets and costumes. The warmth, colour and vibrancy of the tropics seemed to liberate new sources of energy and imagination, leading him to what would eventually become a whole new career in designing, building and transforming homes. Not content to rest there, he also designed many furnishings for these homes, particularly for outdoor use.

Messel bought an existing house called Maddox, a simple bay house perched above a small beach on the St. James coast. With the help of his companion Vagn Riis-Hansen, with whom he had a 30-year relationship,[8] and a Barbadian staff, Messel gradually transformed it using all the trademarks of his theatrical design: slender Greek columns, flattened arches, white-on-white interiors splashed with bright spots of colour, elaborate plaster mouldings – an easy mix of baroque and classical. It was his use of the materials and traditions of island architecture that was truly innovative.Wealthy friends clamoured for Messel to design houses for them, both on Barbados and Mustique, and thus began what architect Barbara Hill described as “his work … of converting quite ordinary houses into wonderlands.” As well as his own home, Maddox, he re-designed and supervised the renovations of Leamington House and Pavilion (for the Heinz family), Crystal Springs, Cockade House, Alan Bay and Fustic House. He designed and built Mango Bay from scratch and was commissioned by the Barbados government to restore the old British officers Garrison headquarters in Queens Park, creating an elegant adaptation of it to a theatre and art gallery.

He would probably have gone on to do much more on Barbados, but was lured

away by his friend Colin Tennant and his private island home, Mustique.

Glenconner commissioned Messel to design all the houses built on the island.

Between 1960 and 1978 Messel created some 30 house plans, of which over 18

have so far been built – a tangible and lasting tribute to his genius. But

Barbados remained his first island love and his home, and he died there in

1978, at the age of 74. Fustic House was one of his favourite properties on

Barbados.

One lasting legacy is that his preferred light sage green shade of paint, now known as “Messel Green’ by paint companies in the Caribbean, has been immortalised as many property owners choose this colour for its quintessential Caribbean-ness.

My published books: