Husband Harold Nicolson, Partner Violet Trefusis

Queer Places:

Les Ruches, 10 Avenue des Carrosses, 77210 Avon, France

White Lodge, 40 The Cliff, Brighton BN2 5RE, UK

40 Sussex Square, Brighton BN2, UK

2 Rue Laffitte, 75009 Paris, Francia

34 Hill St, Mayfair, London W1K, UK

182 Ebury St, Belgravia, London SW1W, UK

4 Kings Bench Walk, Temple, London EC4Y 7DL, UK

10 Neville St, Kensington, London SW7 3AR, UK

Long Barn, Long Barn Rd, Sevenoaks Weald, Sevenoaks TN14, UK

Knole House, Sevenoaks TN15 0RP, UK

Sissinghurst Castle Garden, Biddenden Rd, Cranbrook TN17 2AB, UK

St Michael and All Angels, Hartfield TN7 4BD, UK

Victoria

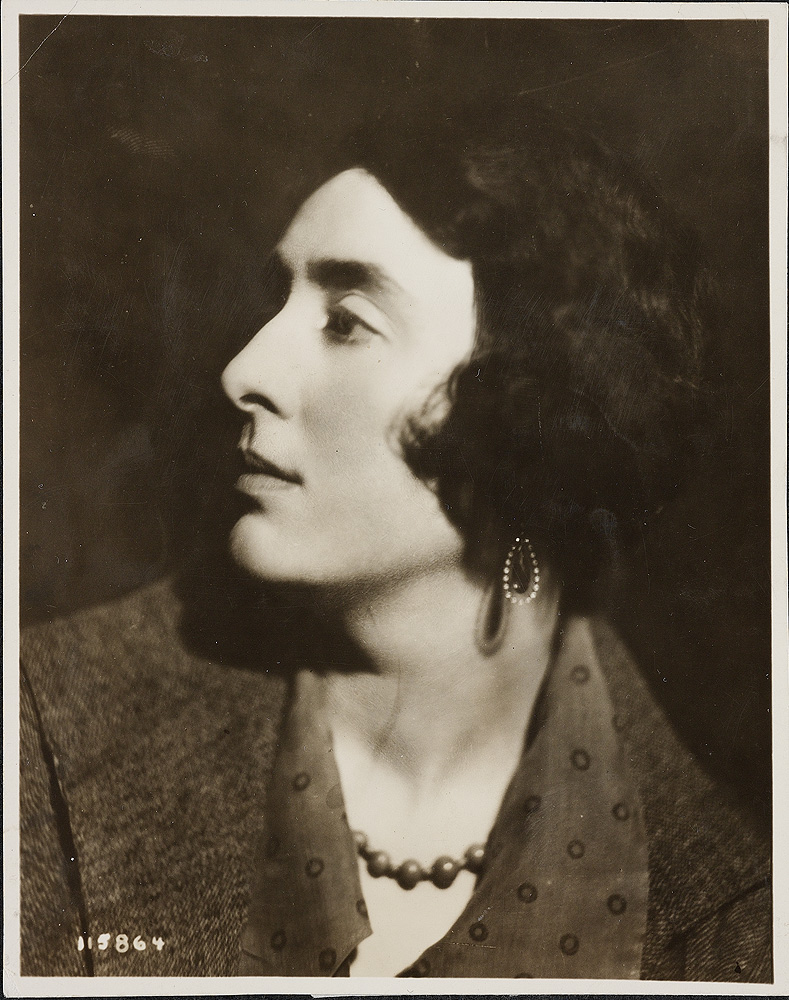

Mary Sackville-West, Lady Nicolson,

CH (9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West,

was an English poet, novelist, and

garden designer.

Virginia Woolf

dedicated Orlando (1928), "To V. Sackville-West".

The most significant episode, in a lesbian reading of the novel, is Orland's

first love affair with Sasha, a Russian princess. Based on

Violet Trefusis,

with whom Vita had her first serious lesbian affair, many aspects of this

character's relationship with Orland reflect Vita and Violet's relationship.

Challenge (1923) contains a fictional self-portrait - Julian Davenant. Eve,

the woman he loves, is a portrait of Violet Trefusis. The titular hero/heroine

of Orlando (1928) by Virginia Woolf is a portrait of Vita. The original

Hogarth Press edition cointained a photograph of Vita, with the caption

"Orlando in about 1840". She appears as Georgiana in

Roy Campbell's The Georgiad (1933).

Campbell's wife,

Mary Garman, was one of Vita's

lovers. Ronald Firbank portrayed Harold Nicolson

and her as The Hon. Harold amd Mrs Chilleywater in The Flower Beneath the Foot

(1923).

Victoria

Mary Sackville-West, Lady Nicolson,

CH (9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West,

was an English poet, novelist, and

garden designer.

Virginia Woolf

dedicated Orlando (1928), "To V. Sackville-West".

The most significant episode, in a lesbian reading of the novel, is Orland's

first love affair with Sasha, a Russian princess. Based on

Violet Trefusis,

with whom Vita had her first serious lesbian affair, many aspects of this

character's relationship with Orland reflect Vita and Violet's relationship.

Challenge (1923) contains a fictional self-portrait - Julian Davenant. Eve,

the woman he loves, is a portrait of Violet Trefusis. The titular hero/heroine

of Orlando (1928) by Virginia Woolf is a portrait of Vita. The original

Hogarth Press edition cointained a photograph of Vita, with the caption

"Orlando in about 1840". She appears as Georgiana in

Roy Campbell's The Georgiad (1933).

Campbell's wife,

Mary Garman, was one of Vita's

lovers. Ronald Firbank portrayed Harold Nicolson

and her as The Hon. Harold amd Mrs Chilleywater in The Flower Beneath the Foot

(1923).

The highbrow novelist Virginia Woolf was able to present same-sex desire in her modernist novel Orlando. Her social postion, as an established novelist and critic, a married woman, and a member of London society, placed Woolf in a potentially more vulnerable situation than her expatriate contemporaries. Despite this, Virginia Woolf's Orlando, published only months after The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall and treating the subject of lesbianism in a much more positive light, escaped suppression to become a mainstream best-seller. The novel was written for, and dedicated to, Vita Sackville-West and was subsequently described by Vita's son, Nigel, as the longest and most charming love-letter in literature. Historians and biographers continue to be divided over the extent to which Vita and Virginia's relationship was lesbian. However, Virginia Woolf's own diary entries and her frequent letters to Vita suggest that she did care passionately for her. In one letter she declared: But I fo adore you, every part of you from heel to hair. Never will you shake me off, try as you may... But if being loved by Virginia is any good, she does do that; and always will, and please believe it. She wrote to Vita up to four times a week furing the height of their relationship, and although Virginia was particularly circumspect about their meetings, even in the privacy of her own diary, their private correspondence gives some indication of the nature of their relationship. Virginia Woolf's letters reveal a playful coyness: Should you say, if I rang up to ask, that you were fond of me? If I saw you would you kiss me? If I were in bed would you, I'm rather excited about Orland tonight: Have been lying by the fire and making up the last chapter.

Lady with a Red Hat 1918

William Strang (1859–1921)

Glasgow Museums

Vita Sackville West by Philip de László (1910)

Vita Sackville-West, 1939, by Gisèle Freund

'View of Long Barn, Kent in Winter' by Mary Margaret Campbell (née Garman), oil painting on paper, about 1927. Long Barn was the home on Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson from 1915-1930.

Sissinghurst Castle Garden, Kent

The long string of Vita's lovers include:

1908 Kenneth Campbell

1909-1911 Rosamund

(Roddie or Rose) Grosvenor

1909 Orazio Pucci

1918-1920

Violet (Eve or Mitya) Trefusis

1921

Dorothy (Dottie) Wellesley

1922

Margaret (Pat) Dansey

1924

Geoffrey Scott

1925

Virginia Woolf

1927 Mary

Garman Campbell

1928

Margaret Goldsmith Voigt

1929 Hilda Matheson

1931

Evelyn Irons

1931

Olive Rinder

1932-1934

Christopher (Christabel Marshal)

St John

1934 Gwen St Aubyn

1947 Violet (Vi) Pym (a neighbor)

1947 Edith Lamont

(a painter)

1947-1952 Cynthia (Bunny) Drummond (her elderly

neighbor's daughter in law)

Vita's travels in France were many, and made quite frequently with her women lovers and companions - notable, of course, with Violet Trefusis, but also with Evelyn Irons, with Gwen St Aubyn, and most famously, with Virginia Woolf.

Sackville-West was a successful novelist, poet, and journalist, as well as a prolific letter writer and diarist. She published more than a dozen collections of poetry during her lifetime and 13 novels. She was twice awarded the Hawthornden Prize for Imaginative Literature: in 1927 for her pastoral epic, The Land, and in 1933 for her Collected Poems. She was the inspiration for the androgynous protagonist of Orlando: A Biography, by her famous friend and lover, Virginia Woolf.

She had a longstanding column in The Observer (1946-1961) and is remembered for the celebrated garden at Sissinghurst created with her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson.

Knole, the home of Vita's aristocratic ancestors in Kent, was given to Thomas Sackville by Queen Elizabeth I in the sixteenth century. [1] Vita was born there, the only child of cousins Victoria Sackville-West and Lionel Edward Sackville-West, 3rd Baron Sackville.[2] Vita's mother, raised in a Parisian convent, was the illegitimate daughter of Lionel Sackville-West, 2nd Baron Sackville and a Spanish dancer, Josefa de Oliva (née Durán y Ortega), known as Pepita. Pepita's mother was an acrobat who had married a barber. [3]

Although the marriage of Vita's parents was initially happy, shortly after the child's birth, the couple drifted and Lionel took an opera singer for a mistress and she came to live with them at Knole. [4]

Christened Victoria Mary Sackville-West, the girl was known as "Vita" throughout her life to distinguish her from her mother, also called Victoria.[5][6]The usual English aristocratic inheritance customs were followed by the Sackville-West family, preventing Vita from inheriting Knole on the death of her father, a source of life-long bitterness to Vita.[7][a] The house followed the title, and was bequeathed instead by her father to his nephew Charles, who became the 4th Baron.

Vita was initially home-schooled by governesses and later attended Helen Wolff's school for girls, an exclusive day school in Mayfair, where she met first loves Violet Keppel and Rosamund Grosvenor. She didn't befriend local children and found it hard to make friends at school. Her biographers characterise her childhood as one filled by loneliness and isolation. She wrote prolifically at Knole, penning eight full-length (unpublished) novels between 1906-1910, ballads, and many plays, some in French. Her lack of formal education led to later shyness with her peers, such as those in the Bloomsbury Group. She felt herself to be sluggish of mind and she was never at the intellectual heart of her social group.[10][11] [12]

Vita's apparently Roma lineage introduced a passion for 'gypsy' ways, a culture she perceived to be hot-blooded, heart-led, dark and romantic. It informed the stormy nature of many of Vita's later love affairs and was a strong theme in her writing. She visited Roma camps and felt herself to be at one with them. [13]

Vita's mother had a wide array of famous lovers, including financier J P Morgan and Sir John Murray Scott (from 1897-1912, until his death). Scott, secretary to the couple who inherited and developed the Wallace Collection, was a devoted companion and Lady Sackville and he were rarely apart during their years together. During her childhood, Vita spent a great deal of time in Scott's apartments in Paris, perfecting her already fluent French. [14]

Vita debuted in 1910, shortly after the death of King Edward VII. She was wooed by Orazio Pucci, son of a distinguished Florentine family, by Lord Granby and Lord Lascelles, among others. In 1914 she had a passionate affair with historian Geoffrey Scott. Scott's marriage collapsed shortly thereafter, as was often the fallout with Vita's affairs, all with women after this point.[15][16]

Vita fell in love with Rosamund Grosvenor (1888 – 1944), who was four years her senior. [b] In her journal Vita wrote "Oh, I dare say I realized vaguely that I had no business to sleep with Rosamund, and I should certainly never have allowed anyone to find it out," but she saw no real conflict.[17]:29–30 Lady Sackville, Vita's mother, invited Rosamund to visit the family at their villa in Monte Carlo (1910). Rosamund also stayed with Vita at Knole House, at Murray Scott's pied a terre on the Rue Laffitte in Paris, and at Sluie, Scott's shooting lodge in the Scottish Highlands, near Banchory. Their secret relationship ended in 1913 when Vita married. [18][19]

Vita was more deeply involved with Violet Keppel, daughter of the Hon. George Keppel and his wife, Alice Keppel. The sexual relationship began when they were both in their teens and strongly influenced them for years. Both later married and became writers. [20]:148

Sackville-West was courted for 18 months by young diplomat Harold Nicolson, whom she found to be a secretive character. She writes that the wooing was entirely chaste and throughout they did not so much as kiss. [21]:68 In 1913, at age 21, Vita married him in the private chapel at Knole. [c] Vita's parents were opposed to the marriage on the grounds that "penniless" Nicolson had an annual income of only £250. He was the third secretary at the British Embassy in Constantinople and his father had been made a peer only under Queen Victoria. Another of Sackville-West's suitors, Lord Granby, had an annual income of £100,000, owned vast acres of land and was heir to an old title, the Duchy of Rutland.[21]:68

The couple had an open marriage. Both Sackville-West and her husband had same-sex relationships before and during their marriage, as did some of the Bloomsbury Group of writers and artists, with whom they had connections.[22][23]:127 Sackville-West saw herself as psychologically divided into two: one side of her personality was more feminine, soft, submissive and attracted to men while the other side was more masculine, hard, aggressive and attracted to women.[23]

Following the pattern of his father's career, Harold Nicholson was at various times a diplomat, journalist, broadcaster, Member of Parliament, and author of biographies and novels. After the wedding the couple lived in Cihangir, a suburb of Constantinople (now Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Sackville-West loved Constantinople, but the duties of a diplomat's wife did not appeal to her. It was only during this time that she attempted to don, with good grace, the part of a "correct and adoring wife of the brilliant young diplomat", as she sarcastically wrote.[21]:97 [21]:95 When she became pregnant, in the summer of 1914, the couple returned to England to ensure that she could give birth in a British hospital.

The family lived at 182 Ebury Street, Belgravia [24] and bought Long Barn in Kent as a country house (1915 - 1930). They employed the architect Edwin Lutyens to make improvements to the house. The British declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914, following Ottoman naval attacks on Russia, precluded any return to Constantinople. [21]:131

The couple had two children: Nigel, who became a well-known editor, politician, and writer, and Benedict Nicolson, an art historian. Another son was stillborn in 1915. His biographer writes:

Harold had a series of relationships with men who were his intellectual equals, but the physical element in them was very secondary. He was never a passionate lover. To him sex was as incidental, and about as pleasurable, as a quick visit to a picture-gallery between trains. [25]

Sackville-West continued to receive devoted letters from her lover Violet Keppel. She was deeply upset to read of Keppel's engagement.[21]:131 Her response was to travel to Paris to see Keppel and persuade her to honour their commitment. Keppel, depressed and suicidal, did eventually marry her fiancée Major Trefusis, under pressure from her mother, though Keppel made it clear that she did not love her husband.[26]:62 Sackville-West called the marriage her own greatest failure.[26]:65

Sackville-West and Keppel disappeared together several times from 1918 on, mostly to France. One day in 1918 Vita writes that she experienced a radical 'liberation', where her male aspect was unexpectedly freed.[27] She writes: "I went into wild spirits; I ran, I shouted, I jumped, I climbed, I vaulted over gates, I felt like a schoolboy let out on a holiday... that wild irresponsible day".[28]

The mothers of both women joined forces to sabotage the relationship and force their daughters back to their husbands.[26] But they were unsuccessful. Vita often dressed as a man, styled as Keppel's husband. The two women made a bond to remain faithful to one another, pledging that neither would engage in sexual relations with their husband. [d]

Keppel continued to pursue her lover to great lengths, until Sackville-West's affairs with other women finally took their toll. In November 1919, while staying at Monte Carlo, Sackville-West wrote that she felt very low, entertaining thoughts of suicide, believing that Nicolson would be better off without her.[23] In 1920 the lovers ran off again to France together and their husbands chased after them in a small two-seater aeroplane. [29] Sackville-West heard allegations that Keppel and her husband Trefusis had been involved sexually, and she broke off the relationship as the lesbian oath of fidelity had been broken. [23] Despite the rift, the two women stayed devoted to one another.

In the 1920s she became closely associated with lesbian and bisexual women in writing and artistic circles, such as Tamara de Lempicka and Colette.

Her relationship with the prominent writer Virginia Woolf commenced in 1925 and ended in 1935, reaching its height between 1925-28.[32]:195-214 The American scholar Louise DeSalvo wrote that the ten years between 1925-35 were the artistic peak of both women's careers as the two had a positive influence on one another: "neither had ever written so much so well, and neither would ever again reach this peak of accomplishment".[32]:195-214 [e]

In December 1922 Sackville-West first met Virginia Woolf at a dinner party in London.[32]:197 Though Sackville-West came from an aristocratic family that was far richer than Woolf's middle class background, the women bonded over their confined childhoods and emotionally absent parents.[32]:198 Woolf knew about Sackville-West's relationship with Keppel and was impressed by the free spirit at play.[33] [f] [g]

Sackville-West greatly admired Woolf's writings, considering her to be the better author, telling Woolf in one letter: "I contrast my illiterate writing with your scholarly one, and I am ashamed".[32]:202 Though Woolf envied Sackville-West's ability to write quickly, she was inclined to believe that the volumes were created too much in haste: "Vita's prose is too fluent".[32]:202 [h]

The two grew close and Woolf disclosed how, as a child, she had been abused by her step-brother. [i] It was largely due to Sackville-West's support that Woolf began to heal the damage, allowing her for the first time to have a satisfying erotic relationship. [j] Woolf purchased a mirror during a trip to France with her lover, saying she felt she could look in a mirror for the first time in her life. Sackville-West counselled her to have greater confidence in her many strengths and to cast off the self-image of the sickly semi-recluse. She persuaded Woolf that her nervous ailments had been misdiagnosed, and that she should focus on her own varied intellectual projects; that she must learn to rest. [k] [32]:199[32]:200 [32]:201

To help the Woolfes, Sackville-West chose their Hogarth Press to be her publisher. Seducers in Ecuador, the first Sackville-West novel to be published by Hogarth, did not sell well, selling only 1500 copies in its first year, but the next, The Edwardians, was a huge success and sold 30000 copies in its first six months. The boost helped Hogarth financially, though Woolf did not always value the books' romantic themes. The increased security of the Press's fortunes allowed Woolf to write more experimental novels such as The Waves[32]:201 Though Woolf is generally considered today to be the better writer, in the 1920s Sackville-West was viewed by the critics as the more accomplished author and her books outsold Woolf's by a large margin.[26]:66-67 [l]

Sackville-West loved to travel, frequently going to France, Spain and to visit Nicolson in Persia, and these trips were emotionally draining for Woolf, who missed Sackville-West intensely. Woolf's novel To the Lighthouse with its theme of longing for someone who is not there was inspired partly by the frequent absences of Sackville-West. Woolf was inspired by Sackville-West to write one of her most famous novels, Orlando, featuring a protagonist who changes sex over the centuries. This work was described by Sackville-West's son Nigel Nicolson as "the longest and most charming love-letter in literature." [32]:204

There were, however, tensions in the relationship. Woolf was often bothered by what she viewed as Sackville-West's promiscuity, charging that the great need for sex led her to take up with anyone who struck her fancy.[32]:213 In A Room Of One's Own (1929), Woolf attacks patriarchal inheritance laws, which was meant to be an implicit criticism of Sackville-West, who never questioned the leading social and political position of the aristocracy to which she belonged. She felt that Sackville-West was unable to critique the system she was both a part of and, to a certain extent, a victim of.[32]:209-210 In the 1930s they clashed over Nicolson's "unfortunate" involvement with Oswald Mosley and the New Party (later renamed the British Union of Fascists) [m] and they were at odds over the looming war. Sackville-West supported rearmament while Woolf remained loyal to her pacifism, leading to an end of their relationship in 1935.[32]:214

One of Vita's male suitors, Henry Lascelles, would later marry the Princess Royal and become the 6th Earl of Harewood.[34]

In 1927 Sackville-West had an affair with Mary Garman, a member of the Bloomsbury Group and between 1929 and 1931 with Hilda Matheson, head of the BBC Talks Department.[35] In 1931, Sackville-West was in a ménage à trois with journalist Evelyn Irons and Irons's lover, Olive Rinder. Irons had interviewed Vita after her novel The Edwardians had become a best-seller.[36][37]

Christopher St John was a British campaigner for women's suffrage, a playwright and author. Edith Craig lived with Christopher St. John from 1899 until Craig's death in 1947, with Clare "Tony" Atwood joining them from 1916.[2][3][4][5] In 1932 St. John fell passionately in love with Vita Sackville-West; this caused huge rows between St. John and Craig, with Atwood unsuccessfully trying to act as peacemaker. The affair dragged on into 1934.

Vita Sackville-West died at Sissinghurst in June 1962, aged 70, from abdominal cancer.[57] She was cremated and ashes buried in the family crypt within the church at Withyham, eastern Sussex.[58]

Sissinghurst Castle is owned by the National Trust. Her son Nigel Nicolson lived there after her death, and following his death in 2004 his own son Adam Nicolson, Baron Carnock, came to live there with his family. With his wife, the horticulturalist Sarah Raven, they committed to restore the mixed working farm and growing food on the property for residents and visitors, a function that had withered under the aegis of the Trust.[59]

The film Vita & Virginia began filming in September 2017. Its current cast include Elizabeth Debicki and Isabella Rossellini. It is directed by Chanya Button and based on a play by Eileen Atkins, created from the love letters between Sackville-West and Woolf. The play was first performed in London in October 1993 and off Broadway in November 1994.[60]

My published books: