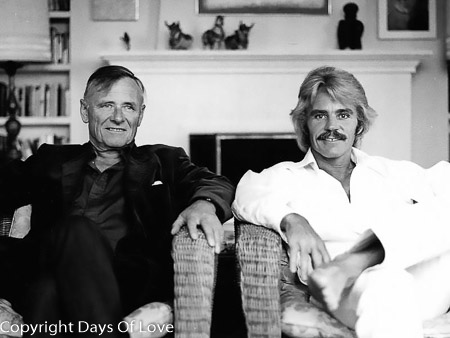

Partner William "Bill" Caskey, Don Bachardy

Queer Places:

St. Edmund's School, Portsmouth Rd, Hindhead GU26 6BH, UK

Repton School, Willington Rd, Repton, Derby DE65 6FH, Regno Unito

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

California State University, Los Angeles, 5151 State University Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90032, Stati Uniti

King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, Regno Unito

Institute for Sexual Science, Tiergarten, Berlino, Germania

Wybersley Hall, 24 Wybersley Rd, High Lane, Stockport SK6 8HB, Regno Unito

36 St Mary Abbots Terrace, Kensington, London W14 8NU, Regno Unito

19 Pembroke Gardens, Kensington, London W8 6HT, Regno Unito

Wassertorstraße 21A, 10969 Berlin, Germania

Admiralstraße 38, 10999 Berlin, Germania

Nollendorfstraße 17, 10777 Berlin, Germania

400 S Saltair Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90049, USA

145 Adelaide Dr, Santa Monica, CA 90402, Stati Uniti

824 Buck Ln, Haverford, PA 19041

333 E Rustic Rd, Santa Monica, CA 90402

Christopher

William Bradshaw Isherwood (26 August 1904 – 4 January 1986) was an

English-American novelist.[1][2]

His best-known works include The Berlin Stories (1935–39), two

semi-autobiographical novellas inspired by Isherwood's time in Weimar Republic

Germany. These enhanced his postwar reputation when they were adapted first

into the play I Am a Camera (1951), then the 1955 film of the same

name, I am a Camera; much later (1966) into the bravura stage musical

Cabaret which was acclaimed on Broadway, and Bob Fosse's inventive

re-creation for the film Cabaret (1972). His novel A Single Man

was published in 1964 and adapted into the film of the same name in 2009.

Christopher

William Bradshaw Isherwood (26 August 1904 – 4 January 1986) was an

English-American novelist.[1][2]

His best-known works include The Berlin Stories (1935–39), two

semi-autobiographical novellas inspired by Isherwood's time in Weimar Republic

Germany. These enhanced his postwar reputation when they were adapted first

into the play I Am a Camera (1951), then the 1955 film of the same

name, I am a Camera; much later (1966) into the bravura stage musical

Cabaret which was acclaimed on Broadway, and Bob Fosse's inventive

re-creation for the film Cabaret (1972). His novel A Single Man

was published in 1964 and adapted into the film of the same name in 2009.

Isherwood was born in 1904 on his family's estate close to the Cheshire–Derbyshire border.[3] He was the elder son of Francis Edward Bradshaw Isherwood (1869–1915), known as Frank, a professional soldier who fought in the Boer War and was killed in the First World War, and his wife Kathleen (née Machell Smith; 1868–1960), whose family were successful merchants.[4] Frank Isherwood was the son of John Henry Isherwood, head of the landed gentry family of Isherwood of Marple Hall and Wyberslegh Hall, Cheshire, and a descendant of the regicide John Bradshaw.[5] The Isherwood family estates came into their possession on the marriage of Mary Bradshaw (of the family that had held them for centuries) to Nathaniel Isherwood, a felt-maker from Bolton, Lancashire, in the early 1700s.[6][7]

At Repton School in Derbyshire, Isherwood met his lifelong friend Edward Upward with whom he wrote the extravagant "Mortmere" stories, of which one was published during his lifetime, a few others appeared after his death, and others he summarised in Lions and Shadows. He deliberately failed his tripos and left Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, without a degree in 1925. For the next few years he lived with violinist André Mangeot, worked as secretary to Mangeot's string quartet and studied medicine. During this time he wrote a book of nonsense poems, People One Ought to Know, with illustrations by Mangeot's eleven-year-old son, Sylvain. It was not published until 1982.

Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden by

Carl Van Vechten

Don Bachardy and Christopher Isherwood by

David Hockney

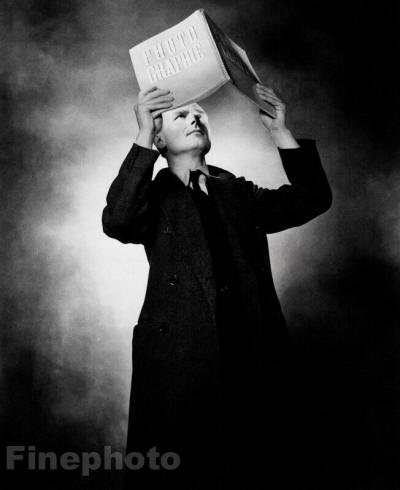

Christopher Isherwood by George

Platt Lynes

In 1925 A. S. T. Fisher reintroduced him to W. H. Auden,[8][9][10] and Isherwood became Auden's literary mentor and partner in an intermittent, casual liaison. Auden sent his poems to Isherwood for comment and approval. Through Auden, Isherwood met Stephen Spender, with whom he later spent much time in Germany. His first novel, All the Conspirators, appeared in 1928. It was an anti-heroic story, written in a pastiche of many modernist novelists, about a young man who is defeated by his mother. In 1928–29 Isherwood studied medicine at King's College London, but gave up his studies after six months to join Auden for a few weeks in Berlin.

In the 1930s Dwight Ripley kept a residence in London, and with his partner Rupert Barneby mixed in circles that included Dwight's fellow Oxonians W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender, as well as Christopher Isherwood, the Huxleys, the Sitwells, Cyril Connolly and his American wife, Jean Connolly: circles in which the admired standards were for satire in literature and, in society, sarcasm and wit. Jean Connolly, who became one of Dwight's closer friends, was at the center of avant-garde sets on both sides of the Atlantic; she was the only woman, said Auden, who could keep him up all night.

Rejecting his upper class background and embracing his attraction to men, he remained in Berlin, the capital of the young Weimar Republic, drawn by its reputation for sexual freedom. There, he "fully indulged his taste for pretty youths. He went to [Berlin in search of boys and found one called Heinz, who became his first great love."[11] Commenting on John Henry Mackay's Der Puppenjunge (The Pansy), Isherwood wrote: "It gives a picture of the Berlin sexual underworld early in this century which I know, from my own experience, to be authentic."[12]

In 1931 he met Jean Ross, the inspiration for his fictional character Sally Bowles. He also met Gerald Hamilton, the inspiration for the fictional Mr Norris. In September 1931 the poet William Plomer introduced him to E. M. Forster. They became close and Forster served as his mentor. Isherwood's second novel, The Memorial (1932), was another story of conflict between mother and son, based closely on his own family history. During one of his return trips to London he worked with the director Berthold Viertel on the film Little Friend, an experience that became the basis of his novel Prater Violet (1945). He worked as a private tutor in Berlin and elsewhere while writing the novel Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935) and a short novel called Goodbye to Berlin (1939), often published together in a collection called The Berlin Stories. These works provided the inspiration for the play I Am a Camera (1951), the 1955 film I am a Camera (both starring Julie Harris), Yes/Buggles' song "Into the Lens/I am a Camera" (1980), the Broadway musical Cabaret (1966) and the film (1972) of the same name. In 1932 he met and fell in love with a young German man named Heinz Neddermeyer.[13]

Christopher Isherwood was at Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute on the day that André Gide was given a guided tour, Gide ‘in full costume as The Great French Novelist, complete with cape’. Retrospectively calling him a ‘Sneering culture-conceited frog!’ from the safety of the mid-1970s – and in doing so sounding like a rather uptight, Francophobic D.H. Lawrence – Isherwood failed to consider that Gide’s pose might have been a way of giving Hirschfeld’s project the serious imprimatur of a symbolic cultural visit, to which the cape and the performed ‘greatness’ were essential embellishments.

After leaving Berlin in 1933, Isherwood and Heinz moved around Europe, and lived in Copenhagen, Sintra and elsewhere. Heinz was arrested as a draft-evader in 1937 following his brief return to Nazi Germany after he was ejected from Luxembourg as an "undesirable alien". Convicted of "reciprocal onanism",[14] he was sentenced to six months in prison, a year of state labour and two years of compulsory military service.[15] Isherwood collaborated on three plays with Auden: The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), The Ascent of F6 (1936), and On the Frontier (1939). Isherwood wrote a lightly fictionalised autobiographical account of his childhood and youth, Lions and Shadows (1938), using the title of an abandoned novel. Auden and Isherwood traveled to China in 1938 to gather material for their book on the Sino-Japanese War called Journey to a War (1939). In 1939, Auden and Isherwood set sail for the United States on temporary visas, a controversial move, later regarded by some as a flight from danger on the eve of war in Europe.[16] Evelyn Waugh, in his novel Put Out More Flags (1942), included a caricature of Auden and Isherwood as "two despicable poets, Parsnip and Pimpernel", who flee to America to avoid the Second World War.[17]

W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood had left England in January 1939. Auden stayed in New York, but Isherwood went on to Los Angeles, where he joined Dwight Ripley's still closer friends, Christopher Wood and Gerald Heard, who had emigrated along with Aldous Huxley, Maria Nys, and son Matthew Huxley two years before. Rupert Barneby obtained a new passport in June, and by October 1939 the two men were in New York.

While living in Hollywood, California, Isherwood befriended Truman Capote, an up-and-coming young writer who would be influenced by Isherwood's Berlin Stories, most specifically in the traces of the story "Sally Bowles" that surface in Capote's famed novella, Breakfast at Tiffany's.[18]

Isherwood also had a close friendship with the British writer Aldous Huxley, with whom he sometimes collaborated. Gerald Heard had introduced Huxley to Vedanta (Upanishad-centered philosophy) and meditation. Huxley became a Vedantist in the circle of Hindu Swami Prabhavananda, and introduced Isherwood to the Swami's Vedanta circle.[19] Isherwood became a convinced Vedantist himself and adopted Prabhavananda as his own guru, visiting the Swami every Wednesday for the next 35 years and collaborating with him on a translation of the Bhagavad Gita.[20] The process of conversion to Vedanta was so intense that Isherwood was unable to write another novel between the years 1939-1945, while he immersed himself in study of the Vedas.[21]

Isherwood also befriended Dodie Smith, a British novelist and playwright who had also moved to California, and who became one of the few people to whom Isherwood showed his work in progress.[22]

In late 1939, Rupert Barneby and Dwight Ripley lived at Padre Hotel, Hollywood, and they became part of the wartime colony of English expatriates that soon flourished along the southern California coast. At the beginning of WWII, Jean Connolly moved to Los Angeles and brought her close friend, Denham Fouts, a storied young American who was the lover then of Peter Watson, the wealthy publisher of Horizon, and was widely assumed to have been, before that, the lover of Prince Paul of Greece. These are the figures satirized by Christopher Isherwood in his novel Down There on a Visit, a novel in which the portrayal of Jean Connolly as Ruthie is so rude that it confirmed, said Rupert Barneby, Dwight Ripley's longstanding opinion that Isherwood was a snit.

In 1940, during the autumn height of the Blitz, Stephen Spender published an open letter to Christopher Isherwood in the New Statesman. "You can't escape," wrote Spender. "If you try to do so, you are simply putting the clock back for yourself: using your freedom of movement to enable yourself to live still in pre-Munich England." Isherwood, who left long before the Blitz, was annoyed. So was Dwight Ripley. "It takes in all of us refugees," he complained to Rupert Barneby, while implying that there was more than politics at issue. "I shall always think of the Spenders henceforth as Delight and Inez, How bitter they are, and no wonder." Earlier, Spender in fact urged Isherwood to emigrate to America in search of refuge for his German lover, Heinz Neddermeyer. In Dwight's circle of friends, Brian Howard likewise had a German lover, Toni Altmann. After Hitler was named chancellor, Isherwood spent the next four years, Howard the next seven, each contending with a sucession of revoked visas, expired passports, and sudden deportations in their continuing efforts to find asylum or new citizenship for Neddermeyer and Altmann, respectively, and so prevent their eventual repatriation and arrest in Germany. Both Englishmen tried to get their lovers into England, and both were refused on moral grounds. Erika Mann married W.H. Auden and became a British subject overnight. When Neddermeyer was arrested in Paris, it was Tony Bower who went to rescue him. Isherwood joined them in Luxembourg, but from there Neddermeyer was expelled into Germany, where he was arrested, charged with reciprocal onanism ("in fourteen foreign countries and in the German Reich," remembered Isherwood), found guilty, and sentenced to successive terms in prison, at hard labor, and in the army. Brian Howard's efforts on behalf of Toni Altmann were likewise frustrated at the end. Howard was an early and outspoken antifascist, the first Englishman to understand the Nazi threat, claimed Erika Mann, who, when asked to describe his plans for returning to serve England, had responded in language of persuasive spontaneity: "So, really, I have no plans, except to do my best for Toni." Altmann was interned by the French in Toulon in September 1939, then moved to Le Mans, where Howard lost track of him. Howard remained in France trying to locate his lover until, in June the following year, he escaped on a coal freighter that departed Cannes the day before the Germans arrived in Marseilles. Christopher Isherwood wrote that when England rejected Heinz Neddermeyer it became for him, in that instant, "the land of the Others."

Heiz Neddermeyer completed his prison sentene, married, and survived the war while serving in the German army.

Isherwood considered becoming an American citizen in 1945 but balked at taking an oath that included the statement that he would defend the country. The next year he applied for citizenship and answered questions honestly, saying he would accept non-combatant duties like loading ships with food. The fact that he had volunteered for service with the Medical Corps helped as well. At the naturalisation ceremony, he found he was required to swear to defend the nation and decided to take the oath since he had already stated his objections and reservations. He became an American citizen on 8 November 1946.[23]

William Faulkner met Christopher Isherwood at least twice. In 1955, he, Jean Stein, Isherwood, and Gore Vidal saw Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. After the play Vidal and Isherwood engaged in a “desultory conversation [that] convinced Jean that the day of the literary salon was over,” but Faulkner remained distinctly aloof from this conversation and hardly spoke to the others about the play. Later, no longer in company with Isherwood and Vidal, Faulkner admitted to Stein that he did not care for the play. Faulkner first met Isherwood in Hollywood at a party in 1945. Isherwood would recall that, despite being warned not to talk about literature with the reticent Faulkner, he and Faulkner had a pleasant conversation “about Auden and Spender, about their work, with a distant politeness in what sounded like a very British accent”. Isherwood’s recalling a conversation with Faulkner about W. H. Auden and Stephen Spender, gay poets and friends of Isherwood, implies that Faulkner had also read them, which implies that he was generally well read in the works of contemporary writers, including homosexual ones.

Isherwood began living with the photographer William "Bill" Caskey. In 1947, the two traveled to South America. Isherwood wrote the prose and Caskey took the photographs for a 1949 book about their journey entitled The Condor and the Cows.

On Valentine's Day 1953, at the age of 48, he met teenaged Don Bachardy among a group of friends on the beach at Santa Monica. Reports of Bachardy's age at the time vary, but Bachardy later said, "At the time I was probably 16."[24]. In fact, he was 18.[25] Despite the age difference, this meeting began a partnership that, though interrupted by affairs and separations, continued until the end of Isherwood's life.[26]

During the early months of their affair, Isherwood finished—and Bachardy typed—the novel on which he had worked for some years, The World in the Evening (1954). Isherwood also taught a course on modern English literature at Los Angeles State College (now California State University, Los Angeles) for several years during the 1950s and early 1960s.

The 30-year age difference between Isherwood and Bachardy raised eyebrows at the time, with Bachardy, in his own words, "regarded as a sort of child prostitute,"[27] but the two became a well-known and well-established couple in Southern Californian society with many Hollywood friends.

Down There on a Visit, a novel published in 1962, comprised four related stories that overlap the period covered in his Berlin stories. In the opinion of many reviewers, Isherwood's finest achievement was his 1964 novel A Single Man, that depicted a day in the life of George, a middle-aged, gay Englishman who is a professor at a Los Angeles university.[28] The novel was adapted into the film, A Single Man, in 2009. During 1964 Isherwood collaborated with American writer Terry Southern on the screenplay for the Tony Richardson film adaptation of The Loved One, Evelyn Waugh's caustic satire on the American funeral industry.

In 1980, Bruce Voeller commissioned Don Bachardy to create a series of portraits of twelve leaders of the gay and lesbian rights movement. The subjects included Voeller, Phyllis Lyon, Del Martin, Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Troy Perry, Jean O'Leary, Charles Brydon, James Foster, David Goodstein, Morris Kight, Elaine Noble. Many were high-profile business-people, politicians, and publishers as well as influential activists. Bachardy’s partner Christopher Isherwood privately referred to Voeller’s circle as the ‘Gay Elite’. Sittings were largely arranged in Bachardy’s home town of Los Angeles, although a handful were done during a trip he made to New York in October 1980. Following Voeller's death, Lucik presented the portrait series to the Human Sexuality Collection, Cornell University, in 1995.

Isherwood and Bachardy lived together in Santa Monica for the rest of Isherwood's life. Isherwood was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1981, and died of the disease on 4 January 1986 at his Santa Monica home, aged 81. His body was donated to medical science at UCLA, and his ashes were later scattered at sea.[29] Bachardy became a successful artist with an independent reputation, and his portraits of the dying Isherwood became well known after Isherwood's death.[30]

My published books: