Heinz Neddermeyer was a German citizen born about 1915. He is also considered to be the first great love of writer

Christopher Isherwood.

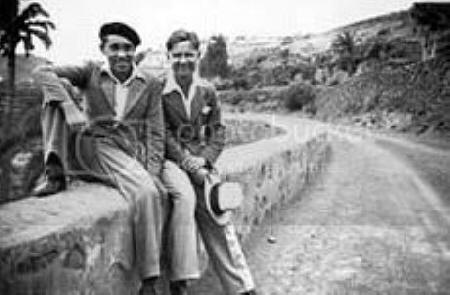

Heinz and Christopher met in Berlin on March 13, 1932 when Heinz was 17.

Christopher would often describe their relationship as an adoption, being the

Heinz was so much younger and not entirely mature. The couple lived together

in Berlin until May 1933 when, due to the uprising of Hitler, they were forced

to flee the country. They traveled Europe and North Africa until May 12, 1937 when Heinz was expelled from Luxembourg and forced to return to Germany. The next day he was arrested by the Gestapo and sentenced to three and half years of forced labor and military service. He survived the forced labor which was brief. Being conditionally free, he married a woman named Gerda in 1938 and had a son named Christian, his only child, in 1940.

Heinz Neddermeyer was a German citizen born about 1915. He is also considered to be the first great love of writer

Christopher Isherwood.

Heinz and Christopher met in Berlin on March 13, 1932 when Heinz was 17.

Christopher would often describe their relationship as an adoption, being the

Heinz was so much younger and not entirely mature. The couple lived together

in Berlin until May 1933 when, due to the uprising of Hitler, they were forced

to flee the country. They traveled Europe and North Africa until May 12, 1937 when Heinz was expelled from Luxembourg and forced to return to Germany. The next day he was arrested by the Gestapo and sentenced to three and half years of forced labor and military service. He survived the forced labor which was brief. Being conditionally free, he married a woman named Gerda in 1938 and had a son named Christian, his only child, in 1940.

In 1940, during the autumn height of the Blitz, Stephen Spender published an open letter to Christopher Isherwood in the New Statesman. "You can't escape," wrote Spender. "If you try to do so, you are simply putting the clock back for yourself: using your freedom of movement to enable yourself to live still in pre-Munich England." Isherwood, who left long before the Blitz, was annoyed. So was Dwight Ripley. "It takes in all of us refugees," he complained to Rupert Barneby, while implying that there was more than politics at issue. "I shall always think of the Spenders henceforth as Delight and Inez, How bitter they are, and no wonder." Earlier, Spender in fact urged Isherwood to emigrate to America in search of refuge for his German lover, Heinz Neddermeyer. In Dwight's circle of friends, Brian Howard likewise had a German lover, Toni Altmann. After Hitler was named chancellor, Isherwood spent the next four years, Howard the next seven, each contending with a sucession of revoked visas, expired passports, and sudden deportations in their continuing efforts to find asylum or new citizenship for Neddermeyer and Altmann, respectively, and so prevent their eventual repatriation and arrest in Germany. Both Englishmen tried to get their lovers into England, and both were refused on moral grounds. Erika Mann married W.H. Auden and became a British subject overnight. When Neddermeyer was arrested in Paris, it was Tony Bower who went to rescue him. Isherwood joined them in Luxembourg, but from there Neddermeyer was expelled into Germany, where he was arrested, charged with reciprocal onanism ("in fourteen foreign countries and in the German Reich," remembered Isherwood), found guilty, and sentenced to successive terms in prison, at hard labor, and in the army. Brian Howard's efforts on behalf of Toni Altmann were likewise frustrated at the end. Howard was an early and outspoken antifascist, the first Englishman to understand the Nazi threat, claimed Erika Mann, who, when asked to describe his plans for returning to serve England, had responded in language of persuasive spontaneity: "So, really, I have no plans, except to do my best for Toni." Altmann was interned by the French in Toulon in September 1939, then moved to Le Mans, where Howard lost track of him. Howard remained in France trying to locate his lover until, in June the following year, he escaped on a coal freighter that departed Cannes the day before the Germans arrived in Marseilles. Christopher Isherwood wrote that when England rejected Heinz Neddermeyer it became for him, in that instant, "the land of the Others."

It was not uncommon for gay men to turn this drastic turn in their lives after being arrested and sentenced to prison by the Nazi party. Although the two continued to correspond, Heinz would not see Christopher again until November of 1952 while Christopher was visiting England and Germany for productions of his "Berlin Stories".

In November 1956 Christopher received a note from Heinz stating that he had been in a political argument at the factory where he worked in East Berlin. Fearing arrest, he fled to Hamburg. Christopher sent him some money. Nothing else is mentioned of Heinz in Christopher's diaries other then fond memories of their past in various cities around Europe and a kind note from Heinz when Christopher's mother passed away in August of 1960.

My published books: