Wife Erika Mann, Partner Chester Kallman

Queer Places:

54 Bootham, York YO30 7XZ, UK

St. Edmund's School, Portsmouth Rd, Hindhead GU26 6BH, UK

Greshams School, Cromer Rd, Holt NR25 6EA, UK

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

43 Chester Row, Belgravia, London SW1W 8JL,

UK

46 Fitzroy St, Fitzrovia, London W1T 5BR, UK

25 Randolph Cres, London W9 1DP, UK

38 Upper Park Rd, London NW3, UK

2 W Cottages, W End Ln, West Hampstead, London NW6 1RJ, UK

559 Finchley Rd, London NW3 7BJ, UK

43 Thurloe Square, Kensington, London SW7 2SR, UK

15 Loudoun Rd, St John's Wood, London NW8 0LS, UK

The Downs School, Brockhill Rd, Malvern WR13 6EY

Mount Holyoke College (Seven Sisters), 50 College St, South Hadley, MA 01075

February House, 7 Middagh St, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA

George Washington Hotel, 23 Lexington Ave, New York, NY 10010, USA

77 St Marks Pl, New York, NY 10003, USA

San Remo Café, 93 Macdougal St, New York, NY 10012, USA

Bective Poplars, Main Walk, Fire Island, NY 11980, USA

Christ Church Cathedral, St Aldate's, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 1DP, UK

Westminster Abbey, 20 Deans Yd, Westminster, London SW1P 3PA, Regno Unito

Kirchstetten, Austria

Wystan

Hugh Auden (21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was an

English-American poet. Hugh Weston in Lions and Shadows (1938) by Christopher

Isherwood is Auden. Nigel Strangeways in Nicholas Blake's (pen-name of

Cecil Day-Lewis) detective novels

is part inspired by Auden. MacSpaunday in

Roy Campbell's Talking Bronco (1946) is a composite of Auden,

Stephen Spender and

Louis MacNeice.

Evelyn Waugh based Parsnip in his

novels Put Out More Flags (1942) and Love Among the Ruins (1953) on Auden. At

the National Theatre in late 2009 Nicholas Hytner directed

Alan Bennett's play The Habit of

Art, about the relationship between the poet W. H. Auden and the composer

Benjamin Britten.

Wystan

Hugh Auden (21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was an

English-American poet. Hugh Weston in Lions and Shadows (1938) by Christopher

Isherwood is Auden. Nigel Strangeways in Nicholas Blake's (pen-name of

Cecil Day-Lewis) detective novels

is part inspired by Auden. MacSpaunday in

Roy Campbell's Talking Bronco (1946) is a composite of Auden,

Stephen Spender and

Louis MacNeice.

Evelyn Waugh based Parsnip in his

novels Put Out More Flags (1942) and Love Among the Ruins (1953) on Auden. At

the National Theatre in late 2009 Nicholas Hytner directed

Alan Bennett's play The Habit of

Art, about the relationship between the poet W. H. Auden and the composer

Benjamin Britten.

Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical

achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its

variety in tone, form and content. He is best known for love poems such as

"Funeral Blues", poems on political and social themes such as "September

1, 1939" and "The Shield of Achilles", poems on cultural and psychological

themes such as ''The Age of Anxiety'', and poems on religious themes such as

"For the Time Being" and "Horae Canonicae."[1][2][3]

The coining of the expression ‘Homintern’ is often attributed to

Cyril Connolly, less often to

Maurice Bowra, and sometimes to

W.H. Auden; but

Anthony Powell thought its source

was Jocelyn Brooke, and

Harold Norse claimed it for himself.

‘Homintern’ was the name Connolly, Auden and others jokingly gave the sprawling,

informal network of friendships that Cold War conspiracy theorists would later

come to think of as ‘the international homosexual conspiracy’.

He was born in York, grew

up in and near Birmingham in a professional middle-class family. In 1915, at the

age of eight, Auden enrolled in Saint Edmund's, a preparatory school in Surrrey,

where he met Christopher

Isherwood, another student, with whom he began a lifelong friendship. In

1920 Auden enrolled in Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk, where he accepted his

homosexuality, though he remained sexually inexperienced due to the repressive

honor code of the school, which had been fashioned to forestall homosexual

activity among the students. In his final school year, when he fell in love with

John Pudney, he lectured the younger

boy about homosexuality, self-abuse, D.H. Lawrence, socialism and Sigmund Freud.

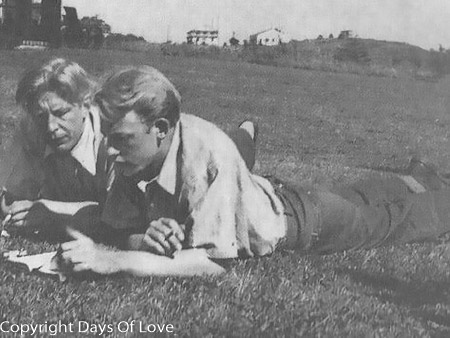

Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden by Carl Van Vechten

W.H. Auden by David Hockney

.jpg)

W.H. Auden by Lotte Jacobi

77 St Marks Pl

Westminster Abbey, London

Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

His sexual boldness notwithstanding, Auden was aware of the need for strategic discretion. He had at least two scares, both involving written indiscretions. The first was in 1923, when his mother found and read a homoerotic poem he had written about his school friend Robert Medley. She passed the poem to her husband, who lectured the two boys about schoolboy intimacy, asked in coy terms if their friendship had ever been sexual, and destroyed the poem. The second incident, potentially far more serious, was in 1934, when he and Isherwood went to meet the latter’s German lover, Heinz, at Harwich. An immigration officer, having read one of Isherwood’s letters to Heinz, doggedly and suspiciously questioned him about the nature of his family’s relationship with this working-class foreigner, before finally refusing to allow Heinz into the country. Auden’s diagnosis of the situation was that the officer had seen through Isherwood at once because he was himself homosexual.

Auden began sleeping with Isherwood in 1926, but by the 1930s his thoughts on sexuality were moving away from sensualism. From around 1926 to 1939 Auden and Isherwood maintained a lasting but intermittent sexual friendship while both had briefer but more intense relations with other men.

Auden entered Christ Church, Oxford, and studied English. After a few months in Berlin in 1928–29 he spent five years (1930–35) teaching in English public schools, then travelled to Iceland and China in order to write books about his journeys.

In the 1930s Dwight Ripley kept a residence in London, and with his partner Rupert Barneby mixed in circles that included Dwight's fellow Oxonians W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender, as well as Christopher Isherwood, the Huxleys, the Sitwells, Cyril Connolly and his American wife, Jean Connolly: circles in which the admired standards were for satire in literature and, in society, sarcasm and wit. Jean Connolly, who became one of Dwight's closer friends, was at the center of avant-garde sets on both sides of the Atlantic; she was the only woman, said Auden, who could keep him up all night.

Auden came to wide public attention at the age of twenty-three, in 1930, with his first book, ''Poems'', followed in 1932 by ''The Orators''.

Auden married Erika Mann in 1935 to secure her safety from the Nazis in Germany. In 1939 he moved to the United States and became an American citizen in 1946.

Three plays written in collaboration with Christopher Isherwood in 1935–38 built his reputation as a left-wing political writer.

Auden and Isherwood sailed to New York City in January 1939, entering on temporary visas. Their departure from Britain was later seen by many as a betrayal, and Auden's reputation suffered. W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood had left England in January 1939. Auden stayed in New York, but Isherwood went on to Los Angeles, where he joined Dwight Ripley's still closer friends, Christopher Wood and Gerald Heard, who had emigrated along with Aldous Huxley, Maria Nys, and son Matthew Huxley two years before. Rupert Barneby obtained a new passport in June, and by October 1939 the two men were in New York.

Auden moved to the United States partly to escape this reputation, and his work in the 1940s, including the long poems "For the Time Being" and "The Sea and the Mirror", focused on religious themes. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for his 1947 long poem ''The Age of Anxiety'', the title of which became a popular phrase describing the modern era.

In April 1939, Isherwood moved to California, and he

and Auden saw each other only intermittently in later years. Around this time,

Auden met the poet Chester Kallman, who became his lover for the next two

years.[4]

In 1939 Harold Norse and Chester Kallman, both recently graduated from Brooklyn College, attended a reading given by Auden and Christopher Isherwood in their first joint appearance in New York. The two graduates seated themselves in the front row with the admitted intent of seducing Auden. Kallman, who succeeded, became Auden's lifetime companion. Auden described their relation as a "marriage" that began with a cross-country "honeymoon" journey.[4]

In 1940, during the autumn height of the Blitz, Stephen Spender published an open letter to Christopher Isherwood in the New Statesman. "You can't escape," wrote Spender. "If you try to do so, you are simply putting the clock back for yourself: using your freedom of movement to enable yourself to live still in pre-Munich England." Isherwood, who left long before the Blitz, was annoyed. So was Dwight Ripley. "It takes in all of us refugees," he complained to Rupert Barneby, while implying that there was more than politics at issue. "I shall always think of the Spenders henceforth as Delight and Inez, How bitter they are, and no wonder." Earlier, Spender in fact urged Isherwood to emigrate to America in search of refuge for his German lover, Heinz Neddermeyer. In Dwight's circle of friends, Brian Howard likewise had a German lover, Toni Altmann. After Hitler was named chancellor, Isherwood spent the next four years, Howard the next seven, each contending with a sucession of revoked visas, expired passports, and sudden deportations in their continuing efforts to find asylum or new citizenship for Neddermeyer and Altmann, respectively, and so prevent their eventual repatriation and arrest in Germany. Both Englishmen tried to get their lovers into England, and both were refused on moral grounds. Erika Mann married W.H. Auden and became a British subject overnight. When Neddermeyer was arrested in Paris, it was Tony Bower who went to rescue him. Isherwood joined them in Luxembourg, but from there Neddermeyer was expelled into Germany, where he was arrested, charged with reciprocal onanism ("in fourteen foreign countries and in the German Reich," remembered Isherwood), found guilty, and sentenced to successive terms in prison, at hard labor, and in the army. Brian Howard's efforts on behalf of Toni Altmann were likewise frustrated at the end. Howard was an early and outspoken antifascist, the first Englishman to understand the Nazi threat, claimed Erika Mann, who, when asked to describe his plans for returning to serve England, had responded in language of persuasive spontaneity: "So, really, I have no plans, except to do my best for Toni." Altmann was interned by the French in Toulon in September 1939, then moved to Le Mans, where Howard lost track of him. Howard remained in France trying to locate his lover until, in June the following year, he escaped on a coal freighter that departed Cannes the day before the Germans arrived in Marseilles.

Auden taught from 1941 to 1945 in American universities, followed by occasional visiting professorships in the 1950s. In 1941 Kallman ended his sexual relationship with Auden because he could not accept Auden's insistence on mutual fidelity,[5] but he and Auden remained companions for the rest of Auden's life, sharing houses and apartments from 1953 until Auden's death.[6] Auden dedicated both editions of his collected poetry (1945/50 and 1966) to Isherwood and Kallman.[7]

From 1947 to 1957 he wintered in New York and summered in Ischia; from 1958 until the end of his life he wintered in New York (in Oxford in 1972–73) and summered in Kirchstetten, Lower Austria.

Auden began summering in Europe, together with Chester Kallman, in 1948, first in Ischia, Italy, where he rented a house, then, starting in 1958, in Kirchstetten, Austria, where he bought a farmhouse from the prize money of the ''Premio Feltrinelli'' awarded to him in 1957,[8] and, he said, shed tears of joy at owning a home for the first time. In 1956–61, Auden was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University where he was required to give three lectures each year; his lectures were popular with students and faculty and served as the basis of his 1962 prose collection ''The Dyer's Hand.'' This fairly light workload allowed him to continue to winter in New York, where he lived at 77 St. Mark's Place in Manhattan's East Village, and to summer in Europe, spending only three weeks each year lecturing in Oxford. He earned his income mostly from readings and lecture tours, and by writing for ''The New Yorker,'' ''The New York Review of Books,'' and other magazines.

In 1963 Kallman left the apartment he shared in New York with Auden, and lived during the winter in Athens while continuing to summer with Auden in Austria. In 1972, Auden moved his winter home from New York to Oxford, where his old college, Christ Church, offered him a cottage, while he continued to summer in Austria. He died in Vienna in 1973, a few hours after giving a reading of his poems at the Austrian Society for Literature; his death occurred at the Altenburgerhof Hotel where he was staying overnight before his intended return to Oxford the next day.[9][10] He was buried in Kirchstetten. Memorials to Auden include one in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.[11]

My published books: