Queer Places:

52 Egmont Rd, Sutton SM2 5JN, Regno Unito

King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, Regno Unito

Denstone College, Denstone, Uttoxeter ST14 5HN, Regno Unito

Hotel Chelsea, 222 W 23rd St, New York, NY 10011, Stati Uniti

36 E 3rd St, New York, NY 10003, Stati Uniti

129 Beaufort St, Chelsea, London SW3 6BS, UK

Quentin

Crisp (born Denis Charles Pratt; 25 December 1908 – 21 November 1999) was an

English writer, raconteur and actor.

Quentin

Crisp (born Denis Charles Pratt; 25 December 1908 – 21 November 1999) was an

English writer, raconteur and actor.

From a conventional suburban background, Crisp enjoyed wearing make-up and painting his nails, and worked as a rent-boy in his teens. He then spent thirty years as a professional model for life-classes in art colleges. The interviews he gave about his unusual life attracted increasing public curiosity and he was soon sought after for his highly individual views on social manners and the cultivating of style. His one-man stage show was a long-running hit both in Britain and America and he also appeared in films and on TV. Crisp defied convention by criticising both gay liberation and Diana, Princess of Wales.

The teenage Quentin Crisp, looking around him for cultural signs of what he felt he was about to become, found a few in newspaper accounts of court cases and in show-business gossip. According to these signs, homosexuality: was thought to be Greek in origin, smaller than socialism but more deadly – especially to children. At about this time The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall was banned. The widely reported court case, together with the extraordinary reputation that Tallulah Bankhead was painstakingly building up for herself as a delinquent, brought Lesbianism, if not into the light of day, at least into the twilight, but I do not remember ever hearing anyone discuss the subject except Mrs Longhurst and my mother.

Crisp remained fiercely independent and unpredictable into old age. He caused controversy and confusion in the gay community by jokingly calling AIDS "a fad", and homosexuality "a terrible disease".[5] He was continually in demand from journalists requiring a sound-bite and throughout the 1990s his commentary was sought on any number of topics.

Quentin Crisp, by Angus McBean, 1941

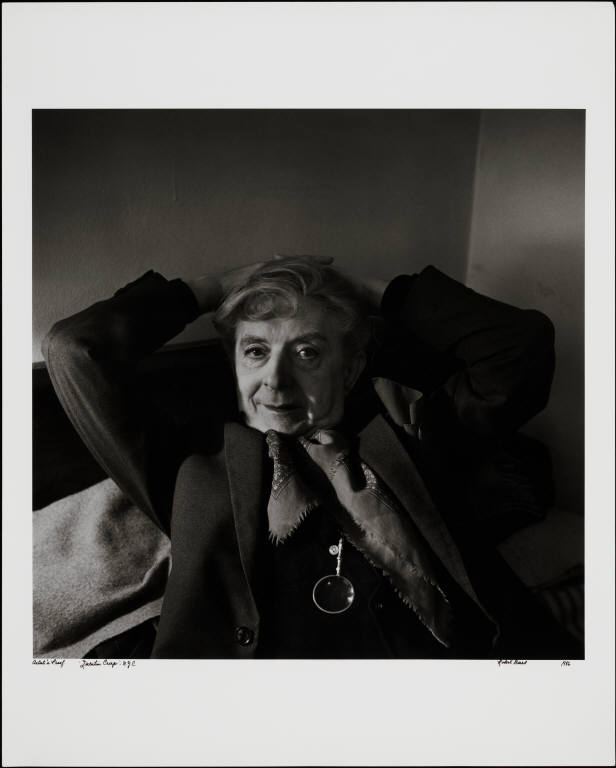

Fergus Greer (born England, lives Los Angeles)

Quentin Crisp

1989

Bromide fibre print

10 1/2 in. x 10 3/8 in. (267 mm x 264 mm)

Given by Fergus Greer, 2006

© National Portrait Gallery, London

© Fergus Greer

Featured in

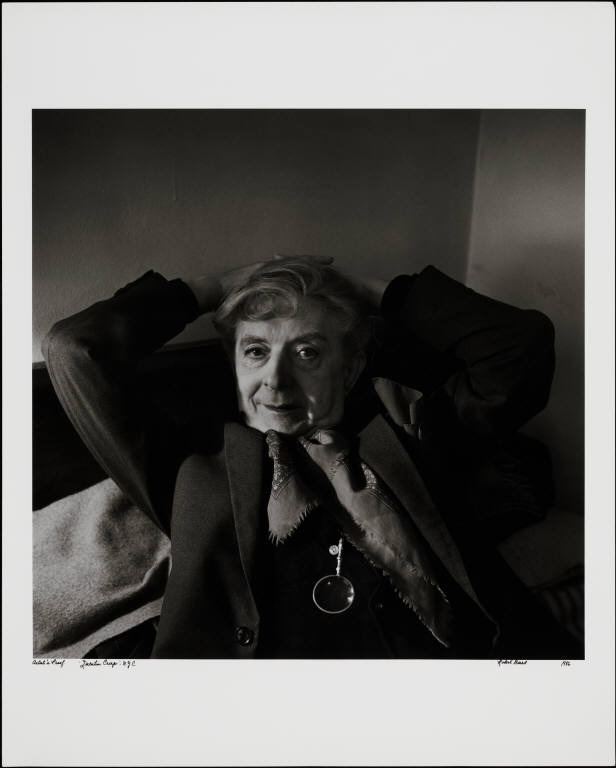

Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay

and Lesbian Writers by Robert Giard [Rights Notice: Copyright Jonathan G. Silin (jsilin@optonline.net)]

.jpg)

Hotel Chelsea, New York City

Some of gay men added make-up to otherwise masculine self-presentation, while others, of whom Quentin Crisp was to become the most famous example, projected a more overtly androgynous self-image. Crisp similarly identified the post-war period – 1948 to be precise – as a time when art met artifice since it was in that year that he changed his hair dye from henna to blue and entered, evoking Picasso, his ‘blue period’.

Crisp was a stern critic of Diana, Princess of Wales and her attempts to gain public sympathy following her divorce from Prince Charles. He stated: "I always thought Diana was such trash and got what she deserved. She was Lady Diana before she was Princess Diana so she knew the racket. She knew that royal marriages have nothing to do with love. You marry a man and you stand beside him on public occasions and you wave and for that you never have a financial worry until the day you die."[6] Following her death in 1997, he commented that it was perhaps her "fast and shallow" lifestyle that led to her demise: "She could have been Queen of England – and she was swanning about Paris with Arabs. What disgraceful behaviour! Going about saying she wanted to be the queen of hearts. The vulgarity of it is so overpowering."[7]

In 1995 he was among the many people interviewed for The Celluloid Closet, an historical documentary addressing how Hollywood films have depicted homosexuality. In his third volume of memoirs Resident Alien published in the same year, Crisp stated that he was close to the end of his life, though he continued to make public appearances and in June of that year he was one of the guest entertainers at the second Pride Scotland festival in Glasgow.

In 1997 Quentin Crisp was crowned king of the Beaux Arts ball run by the Beaux Arts Society. He presided alongside Queen Audrey Kargere, Prince George Bettinger and Princess Annette Hunt.[8]

In December 1998 he celebrated his ninetieth birthday performing the opening night of his one-man show, An Evening with Quentin Crisp, at The Intar Theatre on Forty-Second Street in New York City (produced by John Glines of The Glines organisation). A humorous pact he had made with Penny Arcade to live to be a century old, with a decade off for good behaviour, proved prophetic.

Crisp died of a heart attack in November 1999 nearly one month before his 91st birthday in Chorlton-cum-Hardy in Manchester on the eve of a nationwide revival of his one-man show. He was cremated with a minimum of ceremony as he had requested and his ashes were flown back to Phillip Ward in New York.

He bequeathed his rights in three specific books to his respective collaborators Phillip Ward (for Crisp's final book The Last Word – formerly titled Dusty Answers), Guy Kettelhack (for The Wit and Wisdom of Quentin Crisp) and John Hofsess (for Manners from Heaven). He then bequeathed all future UK-only income (but not the copyrights which belong to Stedman Mays, Mary Tahan and Phillip Ward and are managed by Ward) from his remaining literary estate (including The Naked Civil Servant) to the two men he considered to have had the greatest influence on his career: Richard Gollner, his long-time agent, and Donald Carroll.

My published books: