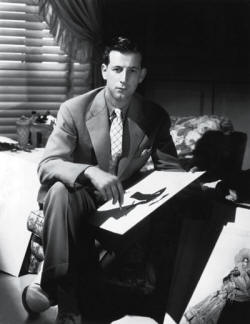

Wife Janet Gaynor

Queer Places:

Parsons School of Design, 66 5th Ave, New York, NY 10011

The French Village, N Highland Ave & Cahuenga Blvd W, Los Angeles, CA 90068

233 N Beverly Dr, Beverly Hills, CA 90210

The Oakridge Estate, 18650 Devonshire St, Northridge, CA 91324

8600 Sunset Blvd, West Hollywood, CA 90069

Hollywood Forever Cemetery Hollywood, Los Angeles County, California, USA, Plot Garden of Legends (formerly Section 8), Lot 193

Adrian Adolph Greenberg (March 3, 1903 — September 13, 1959), widely

known as Adrian, was an American

costume designer whose most famous costumes were for

The Wizard of Oz and other

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and 1940s. During his career, he

designed costumes for over 250 films and his screen credits usually read as "Gowns

by Adrian". On occasion, he was credited as Gilbert Adrian, a

combination of his father's forename and his own.

On August 14, 1939, he married Janet

Gaynor in Yuma,

Arizona.[27]

This relationship has been called a lavender marriage, since Adrian was openly

bisexual while Gaynor was rumored to be gay or bisexual. Paul Gregory, Janet Gaynor's widower, stated in an interview after her passing, that Adrian had told Janet that he had experimented.

Adrian Adolph Greenberg (March 3, 1903 — September 13, 1959), widely

known as Adrian, was an American

costume designer whose most famous costumes were for

The Wizard of Oz and other

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and 1940s. During his career, he

designed costumes for over 250 films and his screen credits usually read as "Gowns

by Adrian". On occasion, he was credited as Gilbert Adrian, a

combination of his father's forename and his own.

On August 14, 1939, he married Janet

Gaynor in Yuma,

Arizona.[27]

This relationship has been called a lavender marriage, since Adrian was openly

bisexual while Gaynor was rumored to be gay or bisexual. Paul Gregory, Janet Gaynor's widower, stated in an interview after her passing, that Adrian had told Janet that he had experimented.

Adrian was born on March 3, 1903, in Naugatuck, Connecticut, to Gilbert Greenberg and Helena Pollack. His mother was a milliner, working first at Lichtenstein's department store in N.Y. then opening Greenburg's, with her husband, Gilbert, who worked for furrier Gunther & Sons, in 1895. Contrary to some sources, Adrian's father Gilbert was born in New York and his mother Helena in Waterbury, Connecticut. It was his grandparents who were immigrants. Joseph Greenburg and his wife Frances were from Russia, while Adolph Pollak and Bertha Mendelsohn were from Bohemia and Germany, respectively. On Church Street, Naugatuck, the Greenbergs were the only Jews, surrounded by Irish Catholics and German Wasps, with names like Murphy and Warner and Andrewss and St. John. Joseph Greenburg owned a fine and dry goods store in Lewiston, Maine. When he passed, it was operated by his wife, Frances, and their daughter, Pearl, Gilbert's sister. Brother Max Greenburg was a scenic designer, working through 1933 for circuses, theatres, and even Paramount Studios for a short time and on both coasts of the U.S. Adolph Pollak ran Pollak & Sons in Waterbury, Connecticut. They were framers and sold prints and some original art.

Gilbert Greenberg ran a milliner's shop in downtown Naugatuck and wanted his son to graduated from Yale Law School, but when he was sixteen, Adrian entered the New York School for Fine and Applied Arts (now Parsons School of Design).[1] During his brief tenure at the school, Adrian formed a close relationnship with one of his teachers, the 26-year-old Robert Kalloch, the same man who had taught Travis Banton several years earlier. Also homosexual, Kalloch was known professionally by just his surname, and he proved influential on Adrian. Kalloch was a guest teacher at the New York School for Fine and Applied Art and did advise Adrian on his career. Kalloch suggested he submit sketches to producers, which is how Adrian got his first stage design work for "George White's Scandals of 1921" at 17 and how he got the job at the Rocky Neck Gloucester Playhouse. His grade and attendance records show that he received A's in all his subjects and graduated in 2 instead of 3 years because he did "extra credit" meaning his contributions to "Scandals" where he was one of four designers. It was because he had good grades that he was recommended for the school's Paris Place des Voges campus.

At the Bal du Grand Prix at the Opera House, where "the young, the raffish, the artists, everyone but the properly respectable" gathered to show off their finery, Adrian watched as Erté, the some years before his MGM contract, was carried in on a platter, his hair and body powdered white and covered with pearls. Erté would remain a fascination. When the flamboyant designer arrived in the United States in 1925, Adrian presented him with a photograph of himself inscribed: "From one who feels like squealing."

While in Paris Adrian was hired by Hassard Short to design the costumes for Irving Berlin's The Music Box Revue. Seeing Adrian's work back in New York, Charles LeMaire, called them "very nice drawings", but predicted they'd never work as costumes. Consequently he votoed much of Adrian's contributions to the show. LeMaire is the only older gay man on record who seemed impervious to Adrian's spell. "He was a charming, slim, elegant boy with a very long face lit up by strange eyes," Erté would recall. It seems there was a feud between Adrian and LeMaire. Orry-Kelly used to refer to LeMaire uncharitably as that "Circus designer". Adrian became friendly with the producer Charles Dillingham, although once again LeMaire scuttled any change of professional advancement from the relationship. Adrian charged that LeMaire was trying to keep him off Broadway. The haughty LeMaire only scoffed. "The trouble is," he said, "you don't design what people want. You design to suit yourself."

Adrian designed Charles Dillingham's "Nifties of 1923". He also worked on "The Magic Ring," "Fashions of 1924," and "Hassard Short's Ritz Review". Adrian designed two sets of costumes for "The Greenwich Village Follies" but left for Hollywood in October of 1924. He was hired by Rudolph Valentino's wife Natacha Rambova to design costumes for A Sainted Devil in 1924. He would also design for Rambova's film, What Price Beauty? (1925). For Valentino's costumes in The Eagle, he interpreted a Russian cossack uniform, and the tall astrakhan hats were copied by fashion designers nationwide. So pleased was Adrian with his work on the film that when Valentino's estate was auctioned after his death in 1926, he bought for himself on of the flaring cossack coats he'd designed for the star.

Choosing not to go back to New York with Valentino after their first pictures were completed, he instead entertained job offers from the studios. Once again, it was a gay man who provided the link: Mitchell Leisen, who seemed as taken with Adrian's looks as he was by his talent. Just five years older, Leisen would nonetheless remember Adian as "just out of high school... I liked his sketches and so did DeMille and he was hired." Leisen's description of Adrian as "just out of high school" is erroneous. In addition to being hired by Irving Berlin and Hassard Short, he was hired by the Distinctive Pictures/Productions Company under Arthur S. Friend in late 1922. After Adrian's first costuming job for Distinctive with "Backbone," he and the film's set designer, Clark Robinson, were both put on staff at Distinctive where Adrian would do half a dozen more films. Before Leisen's account, Adrian had also designed "Her Sister from Paris" for Constance Talmadge, the first film to actually give Adrian onscreen credit. Leisen also said that he had to assist Adrian at the DeMille Studio since he claimed Adrian didn't know how to fit a costume. What is true is that Adrian was hired at DeMille to assist a designer hired by DeMille on the strength of sketches, but who had not been a costumer before. This designer had faked a resumé and immediately ran afoul of Leatrice Joy, the leading actress at DeMille. According to David Chierichetti, "Leisen told me he once traveled from Los Angeles to New York in a stateroom on a train with his costume-designing protege Gilbert Adrian. Adrian woke him up in the middle of the night by tickling his nose with a feather, and Leisen's raised eyebrows conveyed to me the idea that he and Adrian subsequently had sex."

Adrian became head costume designer for Cecil B. DeMille's independent film studio. Samuel Goldwyn's secretary would write to a friend in 1926 about Adrian: "He is very effeminate. The men here kid him so." Adrian decorated the walls of his apartment on Highland Avenue with silver tea papers and was soon seen all over town in a white suit and black cape lined in red satin.

In 1927 Adrian designed costume for the Biblical extravaganza The King of Kings in 1927. DeMille sold his stock in DeMille-Pathé and signed a three-picture deal with M-G-M, starting in August of 1928. Adrian was under personal contract to DeMille until December 1928 and was therefore on loan to M-G-M from June of 1928 to December of 1928 when he signed a one year deal with the studio. His contract was renewed yearly until 1938 when he signed a 3-year deal for $1000 a week. In his career at that studio, Adrian designed costumes for over 200 films. His screen credit, reflecting his preference to design only for women, would read "Gowns by Adrian," rather than the more crass "wardrobe" or "costumes."

During this time, Adrian worked with some of the biggest female stars of the day like Greta Garbo, Norma Shearer, Jeanette MacDonald, Jean Harlow, Katharine Hepburn and Joan Crawford. He worked with Crawford 28 times, Shearer 18 and Harlow 9.

He worked with Garbo over the course of most of her career.[2] The Eugénie hat he created for her in the film Romance became a sensation in 1931 and influenced millinery styles for the rest of the decade.[3][4] For their first collaboration, A Woman of Affairs, Adrian designed clothes that became Garbo trademarks: the famous slouch hat and the loosely belted trenchcoat.

Adrian was behind Crawford's signature outfits with large shoulder pads, which later spawned a fashion trend. For Joan Crawford, he designed clothes fast and furious. Adrian would remark, "Who would ever believe my whole career would rest on Joan Crawford's shoulders?"

For Madam Satan (1930), one of his last collaborations with DeMille before the director left MGM, less was more.

Considering the work of classic Hollywood's gay directors and gay producers, a small but vital subset of the studio system, suggests "queer cinema" might not be such a modern postulate. Occasionally, a convergence of director, producer, writer, and star came together, such as happened with Camille (1937). The gay writer DeWitt Bodeen said that Camille "represents a meeting of talents that were perfect for its interpretation." In fact, wags like to call the picture a rare "all-gay" studio production, and in some ways it comes close: producer David Lewis, director George Cukor, screenwriter Zoe Akins. Greta Garbo, too, and Mercedes de Acosta had a hand in the early draft of the script before Akins took over. Robert Taylor, who played a stunningly beautiful Armand, was rumored to be having an affair with the film's set decorator, Jack Moore. There was also Adrian on costumes and Sydney Guilaroff doing hair. Rex O'Malley infused his Gaston with a natural feyness, a quality perhaps intended by Cukor and Akins, and another gay actor, Rex Evans, played several bit parts. ("Who is that big man and what part is he playing?" Garbo asked Cukor. "That man is Rex Evans," the director replied, "and he's playing the part of a friend who needs a job.") Cukor also manuevered the hiring of another friend, and another gay man, as the picture's true art director, supplanting the ubiquitous Cedric Gibbons, whose contract nonetheless decreed screen credit. This was Oliver Messel, esteemed scenic and costume designer from the London stage, whose outsider status evoked suspicion in the competitive world of the Hollywood studios. It wasn't Messel's first encounter with the studio bureaucracy; in 1935, during the filming of Romeo and Juliet, Cukor had caused a near war by insisting Messel design the costumes instead of Adrian, whom Cukor, according to several friends, viewed as pompous and pretentious. Cukor, as discreet as he was, never tried to obfuscate either his Jewishness or his gayness in the way Adrian did. "I get annoyed with statements that call George "closeted",", said his longtime friend and Los Angeles Times film critic Kevin Thomas. "George was never closeted. He never pretended to be anything he wasn't. He lived according to the rules of his time, that's all."

The hiring of Olivier Messel was done with the assumption that M-G-M would allow producer Irving Thalberg and director George Cukor to make Romeo and Juliet on an original Italian locale. Messel, living in Europe, would be a perfect hire based on his skill and experience. However, when Louis B . Mayer, remembering all too well the trauma and tragedy of the Italian filming of "Ben-Hur" in 1925, forbade it, the film was moved to Culver City and the M-G-M lot where contractually Gibbbons had to art direct and Adrian doubly contracted as both the studio's chief designer and Norma Shearer's personal designer, would have to do the film. Adrian invited Messel to his home and tried to work out a deal which Messel, also a tad self-important, refused. The conflict landed on Mayer's desk. Solomon-like, Mayer split the costumes and sets. No contract said they couldn't have more than one costumer or set designer, so Gibbons and Adrian had to comply. Ungraciously, Messel claimed he tossed all the Adrian designed and made costumes and started over. He even mounted a post-premiere exhibit in England, once again claiming that Adrian did not design the costumes. Humorously, both designers had themselves photographed amid their sketches, making it easier to determine who did what with both designers sharing principal costumes, with Adrian also doing a lot of extras wardrobes.

Cukor's estimation of Adrian is suspect as Cukor was reportedly jealous of any other Hollywood personality hosting "salon" type gatherings which he believed competed with his own. Adrian and Cole Porter both annoyed Cukor by doing so.

"One day Adrian came to me, into my dressing room," remembered the actress Luise Rainer, "and he said, as though he was questioning himself in front of me, "you know, I've fallen in love." I said, "Well, that's wonderful. Who?" He said, "I fell in love with a woman." He was flabbergasted himself." Adrian married Janet Gaynor in 1939, possibly in response to the anti-gay attitudes of the movie studio heads and the sex-negative atmosphere created by the Production Code.[5] Ruth Waterbury wrote up the marriage for Photoplay. "Adrian has never been in love before," she confided to her readers. She also offered a curious assessment: "the little Gaynor" was not what she seemed, but Adrian was "exactly what he looks: sensitive, intelligent, artistic, wordly and utterly charming." They retired and remained married until his death in 1959. Gaynor and Adrian had one son, Robin (born 1940). The press was filled with stories of Adrian designing chic maternity dresses for Janet. It's probably apocryphal that, during labor, doctors feared Gaynor might lose the baby, prompting Adrian to remark, "Oh, no, I'll have to go through that again."

Adrian was most famous for his evening gown designs for these actresses, a talent exemplified in The Women. The Women (1939), filmed in black and white, it originally included a 10-minute fashion parade in Technicolor, which featured Adrian's most outré designs; often cut in TV screenings, it has been restored to the film by Turner Classic Movies. Adrian was also well known for his extravagant costumes, as in The Great Ziegfeld (1936) and opulent period dresses such as those for Camille (1936) and Marie Antoinette (1938). Adrian famously insisted on the best materials and workmanship in the creation of his designs.

Adrian is perhaps best known today for his work on the 1939 movie classic, The Wizard of Oz. Adrian designed the film's red-sequined ruby slippers for Judy Garland.

In 1940, Adrian was voted the number-one American designer in a poll of fashion buyers for US companies; he placed third among all designers worldwide, topped only by Schiaparelli and Hattie Carnegie, and beating out Chanel, Lelong, and Valentina, not to mention Travis Banton and Howard Greer.

Adrian was never as indiscreet in his personal life as Howard Greer or Travis Banton over at Paramount, where the climate was more tolerant than at MGM. But stories still got around, probably apocryphal: a night out with Joan Crawford, both of them picking up men at the Montmarte; attractive young sketch artists being hired more for their looks than for their talent. "Certainly, in the beginning, when I fist met him," recalled his friend, Los Angeles socialite Mignon Winans, "he was with this very tall, handsome, young blondish man. He was open about it."

Adrian left MGM in 1941 to set up his own independent fashion house, though he still worked closely with Hollywood. He bid good-bye to the studio where he'd once reigned like a prince, after a furious row over Greta Garbo's pedestrian costumes in Two-Faced Woman. "When the glamour ends for Garbo," Adrian huffed, "it ends for me." He opened a moderne salon on Beverly Drive and continued designing clothes.

Adrian had been repeatedly courted by retailers to design for public sale, but rebuffed these offers. Macy's "Cinema Shop" copied his work with the studio's tacit approval, much in the same way that department stores produced "Paris" fashions, though they were unapproved copies of the French couturiers' works. He only returned to MGM for a final film, 1952's Lovely to Look At, a Roberta remake. Adrian was never nominated for an Academy Award as the costume category was not introduced during the time of his major work for the studios.

A serious heart attack in 1952 forced the closure of Adrian, Ltd. in Beverly Hills. He and wife Janet bought a fazenda (ranch) in Anápolis, state of Goiás, Brazil's interior and spent a few years, where they had good times with their personal friend Mary Martin. He came out of retirement and returned to the States to design the costumes for "Grand Hotel," a musical version of the 1932 MGM film Grand Hotel, which starred Paul Muni and Viveca Lindfors, but which only played in Los Angeles and San Francisco before Mr. Muni left the Broadway-bound show.

In 1959 he was asked to design costumes for the upcoming Broadway musical Camelot. In the early stages of this project, Adrian died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 56.[6] He was buried in Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

My published books: