Queer Places:

6530 Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90028

Westwood Memorial Park

Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California, USA

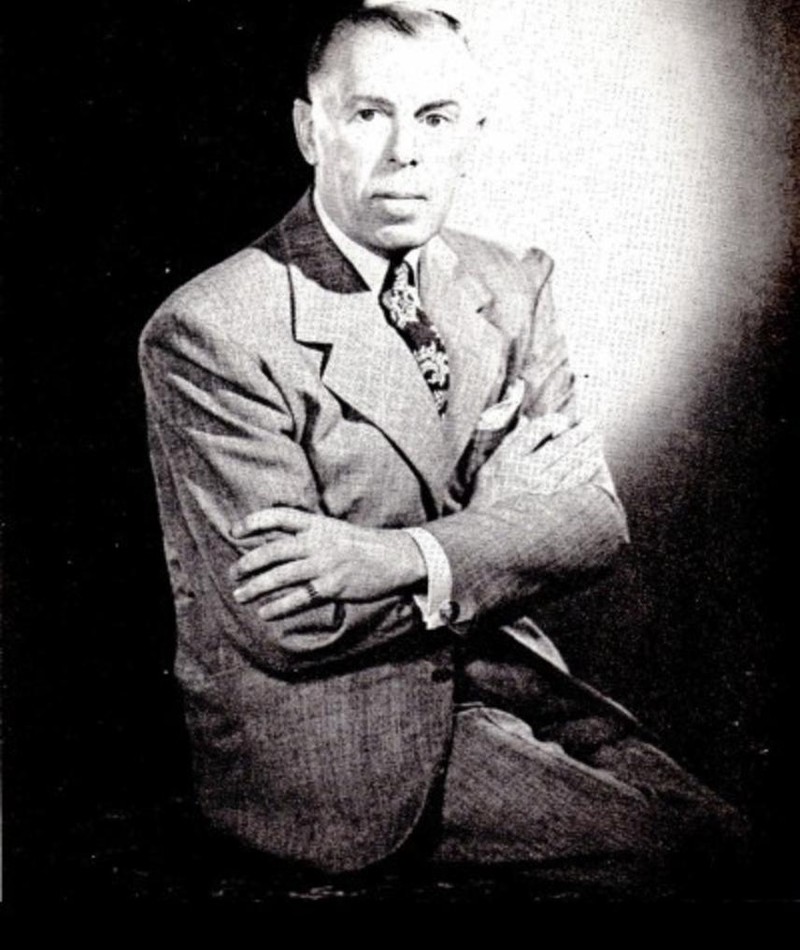

Howard

Greer (16 April 1896 – April 1974, in

Los

Angeles)[1]

was a

Hollywood

fashion designer and a

costume designer in the Golden Age of

American cinema.[2]

Howard

Greer (16 April 1896 – April 1974, in

Los

Angeles)[1]

was a

Hollywood

fashion designer and a

costume designer in the Golden Age of

American cinema.[2]

Bon in 1896 on a farm in Rushville, Illinois, he was from an early age fascinated by fashion and design. The son of Sam and Hattie Greer, poor farmers who barely made a living, Greer was an exception among Hollywood's first gays: drawn from the dirt-poor working class, he seems to have always understood that he was different, and made no attempt to hide the fact.

When he was three, the family moved to the little town of Tecumseh, Nebraska. Investing the family's savings in a hobby that had long obsessed him, Sam Greer opened a florist shop. But while his roses were stunning, the enterprise failed, and the collapse of his dream left Sam Greer "taciturn and disillusioned." In the 1900 Census, he listed his occupations as house painter; he'd been out of work four months. To supplement their income, Hattie took in lodgers.

Young Howard learned about dreams from his father. In a delicious mix of youthful chutzpah and naivete, he began writing to famous people, begging them to rescue him by giving him a job. A few weeks later a telegram arrived from the designer Lady Duff-Gordon, also known as Lucile. "Meet me in Chicago Thursday. Will give definitive answer then." Howard immediately cabled back: "Death alone will keep me from you."

In Chicago, he worked for Lucile as sketch artist. He soon transferred to her New York salon, where he lived with Hubert Julian Stowitts, a ballet star in Anna Pavlova's company. Into this new world, Hattie came to visit. On a stroll through Central Park, she was aghast at lovers kissing publicly on park benches. But Howard "was beyond ebing affected by old-fashioned morals," he remembered. "Howard was always at ease with what he was," said his friend Satch LaValley. "He never had a problem and couldn't understand anyone who did."

Drafted into WWI, he took a shrapnel on the fields of France and survived twice being gassed. His most memorable experience, however, was forming the Argonne Players, a theatrical troupe, where he designed costumes for the "leading lady," played by a male soldier. At war's end, he arranged to be discharged abroad, and took an apartment in Paris, working for Lucille, Paul Poiret, and Edward Molyneux, and designing for the theatre. Writing for Theatre magazine, he became a regular with Isadora Duncan at the salons of Cecile Sorel, "the most famous, the most fascinating, and the most triumphant courtesan of Paris."

He returned to New York in 1921. Working again for Lucile, he also moonlighted, designing costumes for "The Greenwich Village Follies", starring famed female impersonator Bert Savoy. Never far from his working-class roots, Greer worked on such revues to make ends meet: the autocratic Lucille paid him just 25 dollars a week.

Through his theatre work was hired as chief designer for Famous Players-Lasky studios,[2] which was later to emerge from several reorganizations and mergers as Paramount Pictures. His job was to design costumes for the tempestuous Pola Negri. Greer was the first costume designer to be given a contract to head a specific Wardrobe Department. He'd actually been Famous Players' second choice: Gilbert Clark, another Lucile alumnus, had been approached first. Disdaining the movies, Clarke suggested Greer. "He disposed of a rival," Greer recalled, " and I, well, I found my life's work."

Shortly after Howard Greer arrived at Famous Players, he hired as an assistant a mousy little college girl by the name of Edith Head. Boyish and bespectacled, Edith had a husband, but from the start she adopted an ambiguous image of gender and sexuality. Of Mr. Head, she rarely spoke, fueling speculation throughout her life that she was a lesbian. Even a second marriage, to the set designer Wiard Ihnen, failed to derail the rumors; in fact, it was assumed by some that both were gay. "Edith liked to give the impression that it was a marriage of convenience, but it was a loving partnership," said costume historian and Head's longtime friend David Chierichetti. "I think Edith may have rather enjoyed, even encouraged, the speculation. It was helpful for designers to be gay. There was a fraternity of designers, all homosexual. Edith may have actually wanted to be considered gay, or at least to give that impression." She was embraced by Greer and later by Travis Banton, who helped boost her into a career that lasted until the 1980s. "I studied everything Howard Greer and Travis Banton did," she wrote. "They taught me constantly. I couldn't have stayed on a week without them."

"Designers were all rivals, but they were friends," recalled Chierichetti of the costume designers he knew. Photographs often show Greer and Banton socializing together; they were known to be close friends. Even the reclusive Adrian joined them occasionally. Already by the mid-1920s Banton had a reputation around Hollywood, partying late into the night with Howard Greer. "They were big drinkers and carousers. They'd pick up sailors, bring them back for parties. Everyone knew about it. They carried on with abandon."

Greer left his post at Paramount and opened his own couture operation on Sunset Boulevard in December 1927,[2] where he designed custom clothing for the stars until his retirement in 1962. He also continued to create costumes for films into the 1950s, and designed mass-market clothing.

His best known film work includes the Katharine Hepburn films Christopher Strong (1933) and Bringing Up Baby (1938), and the gowns for 1940's My Favorite Wife.

Greer published an autobiography, Designing Male, in 1951.

My published books: