Wife Del Martin

Queer Places:

University of California, Berkeley, CA

651 Duncan St, San Francisco, CA 94131, Stati Uniti

Phyllis

Lyon (November 10, 1924 - April 9, 2020) was a Lesbian activist and gay

marriage trailblazer.

Phyllis

Lyon (November 10, 1924 - April 9, 2020) was a Lesbian activist and gay

marriage trailblazer.

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon are profiled in ''Family: a portrait of gay and lesbian America'', by Nancy Andrews (1994) and ''Living happily ever after: couples talk about lasting love'', by Laurie Wagner, Stephanie Rausser, and David Collier (1996).

The Daughters of Bilitis (pronounced be-LEE-tus and abbreviated DOB) began in 1955 in San Francisco as a middle-class social club for lesbians wishing to avoid the bar scene. Rose Bamberger, a Filipina American, had the initial idea for the group and enlisted the aid of her partner and three other lesbian couples. Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin were one of the couples, and they are more famously associated with the group’s founding. Historians credit Lyon and Martin with switching the group’s focus from socializing to organizing and educating. In 1956, the group began publishing The Ladder, a magazine focused specifically on lesbian lives. Many of the most well-known female activists of the pre-Stonewall gay and lesbian movement—Lyon, Martin, Kay Tobin (Lahusen), and Barbara Gittings—held leadership positions within DOB at one time or another, as did a number of lesbians of color, including Cleo Bonner, Ernestine Eckstein, and Ada Bello.

When Lyon married her partner of 55 years, Del Martin, in 2008, they formed the first legal gay union in California. It was not their first wedding. In 2004, despite state and federal bans on same-sex marriage, Mayor Gavin Newsom of San Francisco began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Lyon and Martin were the first to receive one, but that union would be short-lived. The California Supreme Court invalidated their marriage a month later, arguing that the mayor had exceeded his legal authority.

Four years later, the same court declared same-sex marriages legal and Newsom invited the couple back as the first to be married under the new ruling. Martin died shortly after.

“I am devastated,” Lyon said following her wife’s death. “But I take some solace in knowing we were able to enjoy the ultimate rite of love and commitment before she passed.”

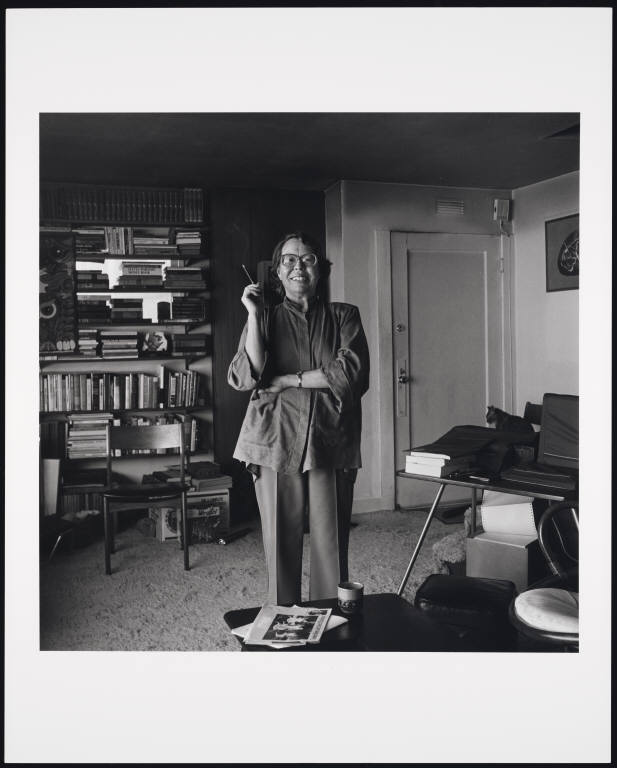

Featured in

Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay

and Lesbian Writers by Robert Giard [Rights Notice: Copyright Jonathan G. Silin

(jsilin@optonline.net)]

University of California, Berkeley, CA

The mauve and turquoise-blue suits that the couple wore to their weddings are in the permanent collection of the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco.

Phyllis Ann Lyon was born on Nov. 10, 1924, in Tulsa, OK, to William Ranft Lyon, a salesman, and Lorena Belle Ferguson, a homemaker. The family moved to Sacramento in the early 1940s.

After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1946 with a degree in journalism, Lyon worked as a reporter for The Chico Enterprise-Record in Chico, CA. She moved to Seattle in 1949 to work at a construction trade journal, where Martin was also employed. They began dating and, on Valentine’s Day in 1953, moved in together in San Francisco.

In 1955, they joined three other lesbian couples to found the Daughters of Bilitis, one of the first lesbian political organizations in the United States. The name was inspired by “Songs of Bilitis,” a collection of lesbian love poems by Pierre Louÿs.

“There were a lot of laws that were anti-gay, and there were more things to do than just party,” Lyon said in an interview for StoryCorps. “We decided we’d put out a newsletter, The Ladder.”

The newsletter, which Lyon edited from its inception in 1956, grew into one of the first lesbian magazines in the country. It published until the group disbanded in the 1970s.

Lyon and Martin also co-wrote two books: “Lesbian/Woman” (1972), which won a Stonewall Book Award, and “Lesbian Love and Liberation” (1973).

“There really weren’t any books” about lesbians when she was growing up, Lyon said in a 1992 interview with Terry Gross of the NPR program “Fresh Air.” “And then there was nothing that was any good in the libraries in those early days.”

Throughout their 55-year relationship, Lyon and Martin were politically engaged. They were among the first lesbians to join the National Organization for Women, and Martin was later elected to its board of directors. The couple also helped form the Council on Religion and the Homosexual to persuade ministers to accept lesbians and gay men into churches.

On the local level, they were members of the Alice B. Toklas Democratic Club, San Francisco’s first gay political organization, which influenced the passage of a bill to ban employment discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 1979, local activists established the Lyon-Martin Health Services, a health care provider, in San Francisco. It is still in operation.

In 1980, Bruce Voeller commissioned Don Bachardy to create a series of portraits of twelve leaders of the gay and lesbian rights movement. The subjects included Voeller, Phyllis Lyon, Del Martin, Frank Kameny, Barbara Gittings, Troy Perry, Jean O'Leary, Charles Brydon, James Foster, David Goodstein, Morris Kight, Elaine Noble. Many were high-profile business-people, politicians, and publishers as well as influential activists. Bachardy’s partner Christopher Isherwood privately referred to Voeller’s circle as the ‘Gay Elite’. Sittings were largely arranged in Bachardy’s home town of Los Angeles, although a handful were done during a trip he made to New York in October 1980. Following Voeller's death, Lucik presented the portrait series to the Human Sexuality Collection, Cornell University, in 1995.

“We were trying to help lesbians find themselves,” Lyon said in a 1989 interview. “I mean, you can’t have a movement if you don’t have people that see that they’re worthwhile.”

Even after Martin’s death, Lyon continued advocating for lesbian rights. “If you got stuff you want to change, you have to get out and work on it,” she said in a 2017 interview with The Bay Area Reporter. “You can’t just sit around and say, ‘I wish this or that was different.’ You have to fight for it.”

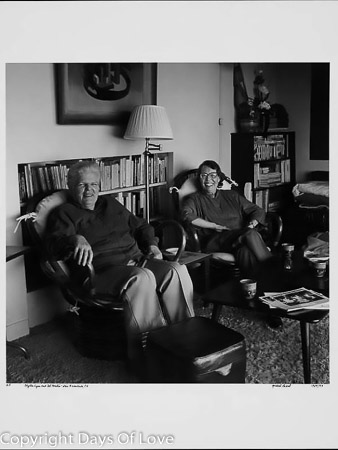

Phyllis Lyon, sixty-eight, and Del Martin, seventy-one, are best known as two of the eight women who founded the Daughters of Bilitis in 1955. At the time there were two other gay groups in the United States: the Mattachine Society and ONE, Inc. Daughters of Bilitis was the first exclusively les¬ bian organization. Chapters spread across the nation, and the group flourished in the 1960s, holding national conventions and garnering the attention of the mainstream media and the FBI. The na¬ tional organization dissolved in 1970. Today, only the Boston chapter remains. The two continue to work for women's and gay rights. They coauthored Lesbian/Woman in 1972, and Del wrote Battered Wives in 1976. The couple of more than forty years first met when they worked for construction-industry trade pub¬ lications in Seattle, Washington. Del was the first person Phyllis had ever met who she knew was a lesbian. They later moved to San Francisco, and they still live in the house they bought there in 1955. Del is divorced, with one daughter and two grandchildren. The two were photographed with their cat, Koala, in their kitchen. Phyllis: We had a phone call from one lesbian. She wanted to know if we would be inter¬ ested in helping to start a social group for lesbians. So we said yes. Del: Everybody was very isolated and closeted. It was difficult to find people to join. We came up with the name Daughters of Bilitis so we would sound like a women's lodge— Daughters of the Nile or Daughters of the American Revolution—and nobody would know that it was a lesbian group. Phyllis: Some had wanted to make it like a women's lodge where you would have ritual membership induction and things along those lines. The rest of us didn't really go for that idea exactly. Another woman brought the Songs of Bilitis to our attention. It was a lesbian narrative poem. She felt that lesbians would know what Daughters of Bilitis meant, but nobody else would. Of course, I don't think most of the lesbians knew what it meant ei¬ ther. We had never heard of this poem. We decided we needed a newsletter. With the very first issue we had about 175 copies be¬ fore the Mattachine Society's mimeograph broke down. A lot of members of DOB didn't use their real names. I became Ann Ferguson. I was editor of The Ladder, our newsletter. I guess it was the idea that my name was going to be in print, and I thought, "Somebody might see it and God knows what would happen, so I'd better not do that." So I took my middle name and my mother's maiden name. Then at the same time we started the newsletter in 1956, we started our public discussion meetings. We rented a room downtown, and people could just come by. People would want to meet Ann Ferguson because they'd seen The Ladder so they'd want to meet the editor. So Del would yell, "Ann Ferguson! Ann! Ann!" And I would never respond, be¬ cause it wasn't my name. Then she'd say, "Phyllis!" and I would turn right around. So we decided that the pseudo¬ nym thing was really ridiculous, and we killed Ann Ferguson.

My published books: