Husband Pierre Martory, David Kermani

Queer Places:

Wesleyan University, 45 Wyllys Ave, Middletown, CT 06459

Deerfield Academy, 7 Boyden Ln, Deerfield, MA 01342

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

New York University, New York, NY 10003

Columbia University (Ivy League), 116th St and Broadway, New York, NY 10027

40 Rue Spontini, 75116 Paris, France

Le Fiacre, 4 Rue du Cherche-Midi, 75006 Paris, France

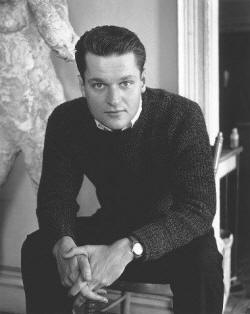

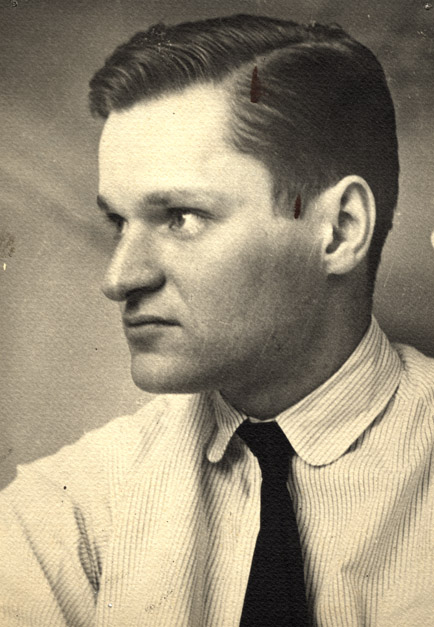

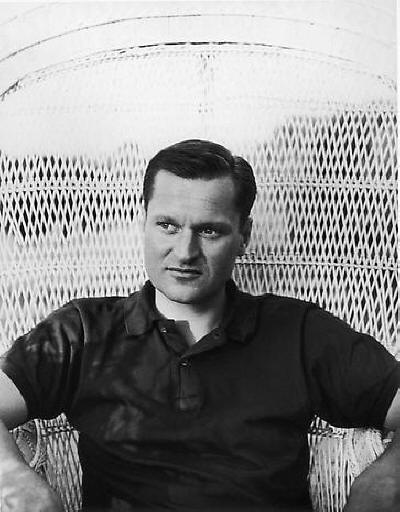

John Lawrence Ashbery[1]

(July 28, 1927 – September 3, 2017) was an American poet.[2]

He published more than twenty volumes of poetry and won nearly every major

American award for poetry, including a

Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his collection

Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Renowned for its postmodern

complexity and opacity, Ashbery's work still proves controversial. Ashbery

stated that he wished his work to be accessible to as many people as possible,

and not to be a private dialogue with himself.[2][3]

At the same time, he once joked that some critics still view him as "a

harebrained, homegrown surrealist whose poetry defies even the rules and logic

of

Surrealism."[4]

John Lawrence Ashbery[1]

(July 28, 1927 – September 3, 2017) was an American poet.[2]

He published more than twenty volumes of poetry and won nearly every major

American award for poetry, including a

Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for his collection

Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Renowned for its postmodern

complexity and opacity, Ashbery's work still proves controversial. Ashbery

stated that he wished his work to be accessible to as many people as possible,

and not to be a private dialogue with himself.[2][3]

At the same time, he once joked that some critics still view him as "a

harebrained, homegrown surrealist whose poetry defies even the rules and logic

of

Surrealism."[4]

Langdon Hammer, chairman of the English Department at Yale University, wrote in 2008, "No figure looms so large in American poetry over the past 50 years as John Ashbery" and "No American poet has had a larger, more diverse vocabulary, not Whitman, not Pound."[5] Stephanie Burt, a poet and Harvard professor of English, has compared Ashbery to T. S. Eliot, calling Ashbery "the last figure whom half the English-language poets alive thought a great model, and the other half thought incomprehensible".[6]

Ashbery was born in Rochester,[7] New York, the son of Helen (née Lawrence), a biology teacher, and Chester Frederick Ashbery, a farmer.[8] He was raised on a farm near Lake Ontario; his brother died when they were children.[9] Ashbery was educated at Deerfield Academy, an all-boys school, where he read such poets as W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas and began writing poetry. Two of his poems were published in Poetry magazine by a classmate who had submitted them under his own name, without Ashbery's knowledge or permission.[10] Ashbery also published a piece of short fiction and a handful of poems—including a sonnet about his frustrated love for a fellow student—in the school newspaper, the Deerfield Scroll. His first ambition was to be a painter: from the age of 11 until he was 15, Ashbery took weekly classes at the art museum in Rochester.

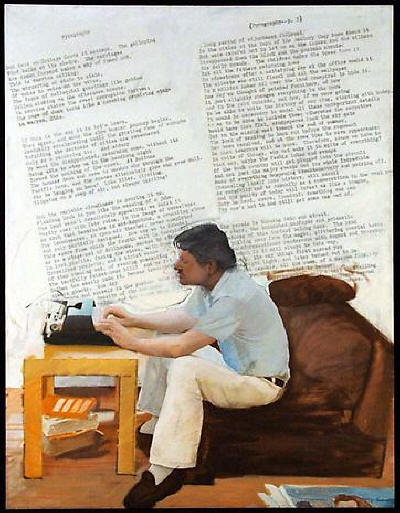

LARRY RIVERS

Pyrography: Poem and Portrait of John Ashbery II

1977

acrylic on canvas

76 x 58 inches

Collection of Kim Manocherian

JOHN JONAS GRUEN

John Ashbery, Water Mill

1964

gelatin-silver print

13 x 10 inches

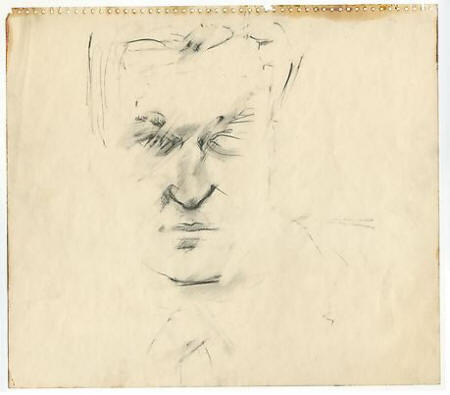

LARRY RIVERS

John Ashbery

1962

pencil on paper

14 x 17 inches

Private Collection

TREVOR WINKFIELD

Book cover for "Rivers and Mountains" by John Ashbery

1977

acrylic on paper

17 1/4 x 20 1/4 inches

TREVOR WINKFIELD

Book cover for "Three Poems" by John Ashbery

1989

acrylic on paper

17 3/4 x 21 1/2 inches

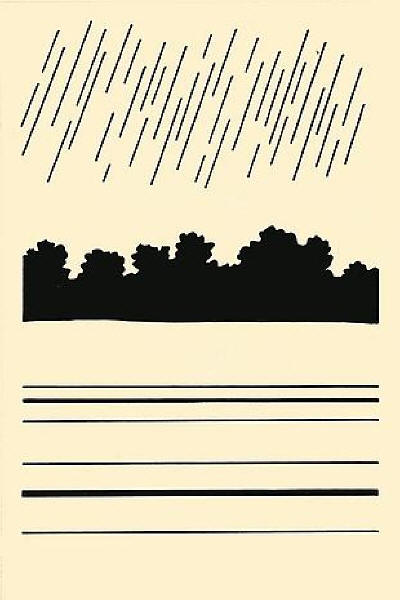

JOE BRAINARD

(Untitled (Rain)

Illustration for "The Vermont Notebook" by John Ashbery

c.1964

ink on paper

9 x 6 inches

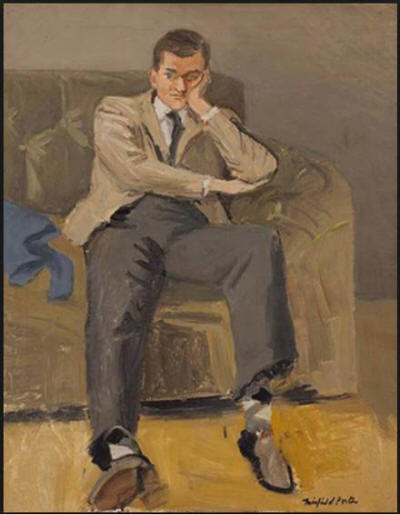

Fairfield Porter’s double portrait of John Ashbery and James Schuyler

PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATE OF ANNE E.C. PORTER

Fairfield Porter

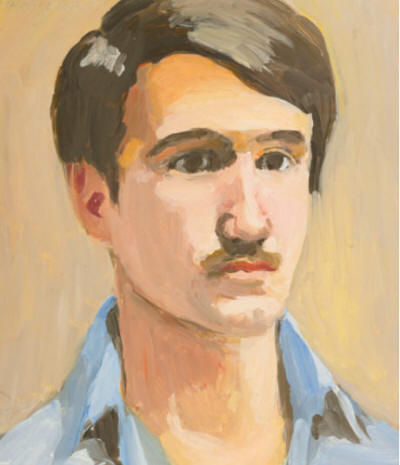

DAVID KERMANI

Portrait of John Ashbery by Fairfeld Porter

Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, NYU, New York City

Ashbery graduated in 1949 with an A.B., cum laude, from Harvard College, where he was a member of the Harvard Advocate, the university's literary magazine, and the Signet Society. He wrote his senior thesis on the poetry of W. H. Auden. At Harvard he befriended fellow writers Kenneth Koch, Barbara Epstein, V. R. Lang, Frank O'Hara and Edward Gorey, and was a classmate of Robert Creeley, Robert Bly and Peter Davison.

In the early 1950s, Edward Gorey, with a group of recent Harvard alumni including Alison Lurie (1947), John Ashbery (1949), Donald Hall (1951) and Frank O'Hara (1950), amongst others, founded the Poets' Theatre in Cambridge, which was supported by Harvard faculty members John Ciardi and Thornton Wilder.[6][7][8] He frequently stated that his formal art training was "negligible"; Gorey studied art for one semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943.[9]

Ashbery went on to study briefly at New York University before receiving an M.A. from Columbia University in 1951. Ashbery did not have any relationships at Harvard until his sophomore year when he heard a man refer to himself as gay and decided to meet him. Then, an affair with another student resulted in Ashbery learning about gay nightlife in Boston. His favorite bar was the Chess Room in the Hotel Touraine because he liked its old-style decorations. He had several sexual encounters with men he met in Harvard Square. But throughout this period, he was careful to keep his sexuality secret from his straight friends. He was not the only one being secretive; a gay couple that Ashbery was friends with moved to Beacon Hill so they could live together. Ashbery began an affair with a sailot he met at the Silver Dollar, but because overnight guests were not allowed in the dorms and homosexuality was grounds for expulsion, the sailor had to sneak out the window of Ashbery's first floor room each night.

In 1951 Dwight Ripley offered to back the Tibor de Nagy Gallery opened by John Bernard Myers as gallery director. Dwight missed the excitement generated by Peggy Guggenheim's art gallery, closed in 1947 when she followed the last of the exiled Surrealist back to Europe. In London, his Oxford contemporary Peter Watson had helped found the Institute of Contemporary Arts and was planning shows to feature the painters Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. Encouraged, probably goaded by this example, Dwight turned to his art-critic friend Clement Greenberg for help. On the Monday evening of January 23, 1950, he took aspiring art dealer John Bernard Myers to Greenberg's apartment in Greenwich Village. "Ripley and John Myers," confirmed Greenberg's biographer 47 years later, "came to Clem's apartment to consult with him about a noncommercial gallery that Ripley would finance as silent backer and Myers would run." Greenberg suggested the initial artists, Dwight wrote the first check, and the result was Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which opened its doors that December and rapidly became one of the influential art galleries in New York. In its first full year Dwight provided the gallery with more than 5.000$, or five time its annual rent. This was an historic contribution. Tibor de Nagy sponsored the first solo shows of Larry Rivers, Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, Fairfield Porter, artists whose works would alter the conventions, then supreme, of Abstract Expressionism. When the gallery's director John Myers published the first chapbooks of poets John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, and Kenneth Koch, Dwight's support altered the conventions of poetry as well.

After working as a copywriter in New York from 1951 to 1955,[11] from the mid-1950s, when Ashbery he received a Fulbright Fellowship, through 1965, Ashbery lived in France.

John Ashbery lived in France for much of the decade between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, earning his living mainly as an art critic for American journals (New York Herald Tribune, Art International, Art News), sharing his life with a Frenchman, Pierre Martory, and improving his own French all the time, until he became a fine translator of French poetry, including that of his lover.

Ashberry was an editor of the 12 issues of Art and Literature (1964–67) and the New Poetry issue of Harry Mathews' Locus Solus (# 3/4; 1962). To make ends meet he translated French murder mysteries, served as the art editor for the European edition of the New York Herald Tribune and was an art critic for Art International (1960–65) and a Paris correspondent for ARTnews (1963–66), when Thomas Hess took over as editor. During this period he lived with the French poet Pierre Martory, whose books Every Question but One (1990), The Landscape is behind the Door (1994) and The Landscapist he translated (2008), as he did Arthur Rimbaud (Illuminations), Max Jacob (The Dice Cup), Pierre Reverdy (Haunted House), and many titles by Raymond Roussel. After returning to the United States, he continued his career as an art critic for New York and Newsweek magazines while also serving on the editorial board of ARTnews until 1972. Several years later, he began a stint as an editor at Partisan Review, serving from 1976 to 1980.

During the fall of 1963, Ashbery became acquainted with Andy Warhol at a scheduled poetry reading at the Literary Theatre in New York. He had previously written favorable reviews of Warhol's art. That same year he reviewed Warhol's Flowers exhibition at Galerie Ileana Sonnabend in Paris, describing Warhol's visit to Paris as "the biggest transatlantic fuss since Oscar Wilde brought culture to Buffalo in the nineties". Ashbery returned to New York near the end of 1965 and was welcomed with a large party at the Factory. He became close friends with poet Gerard Malanga, Warhol's assistant, on whom he had an important influence as a poet. In 1967 his poem Europe was used as the central text in Eric Salzman's Foxes and Hedgehogs as part of the New Image of Sound series at Hunter College, conducted by Dennis Russell Davies. When the poet sent Salzman Three Madrigals in 1968, the composer featured them in the seminal Nude Paper Sermon, released by Nonesuch Records in 1989.[12]

In the early 1970s, Ashbery began teaching at Brooklyn College, where his students included poet John Yau. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1983.[1]

Ashbery once responded to two of Frank O'Hara's poems ("Quite Poem" and "Today") by sending his friend John Brooks Wheelwright's "Why Must You Know?" Ashbery told O'Hara that Wheelwright had been "somewhat like you, though not much." A guarded insight, to be sure, but obviously key to Ashbery's opinion of his friend's work. In fact, after O'Hara's death at age forty, Ashbery remarked that his friend's passing was "the biggest secret loss to American poetry since John Wheelwright was killed by a cat in Boston in 1940." In The New York Times Book Review in 1979, nearly three decades after first comparing Wheelwright's work with O'Hara's, Ashbery listed Wheelwright's collected poems as among the one hundred greatest post-WWII American books. A decade later, Ashbery dedicated the fourth of his Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard to Wheelwright. By then his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror had won the Triple Crown (the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Books Critics Award), and Ashbery significantly emphasized in his Wheelwright lecture the very poem he had sent O'Hara so many lives before, "Why Must You Know?".

In the 1980s, Ashbery moved to Bard College, where he was the Charles P. Stevenson, Jr., Professor of Languages and Literature, until 2008, when he retired but continued to win awards, present readings, and work with graduate and undergraduates at many other institutions. He was the poet laureate of New York State from 2001 to 2003,[13] and also served for many years as a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. He served on the contributing editorial board of the literary journal Conjunctions. In 2008 Ashbery was named the first poet laureate of MtvU, a division of MTV broadcast to U.S. college campuses, with excerpts from his poems featured in 18 promotional spots and the works in their entirety on the broadcaster's website. [14]

Ashbery was a Millet Writing Fellow at Wesleyan University in 2010, and participated in Wesleyan's Distinguished Writers Series.[15] He was a founding member of The Raymond Roussel Society, with Miquel Barceló, Joan Bofill-Amargós, Michel Butor, Thor Halvorssen and Hermes Salceda.

Ashbery lived in New York City and Hudson, New York, with his husband, David Kermani.[16] He died of natural causes on September 3, 2017, at his home in Hudson, at the age of 90.[17][18]

My published books: