Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

8 Strawberry Ln, Yarmouth Port, MA 02675

Woodland Cemetery

Ironton, Lawrence County, Ohio, USA

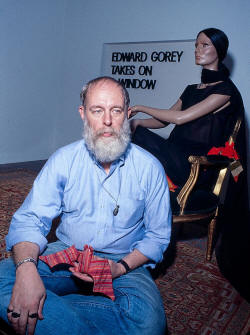

Edward St. John Gorey (February 22, 1925 – April 15, 2000) was an American writer, Tony Award-winning costume designer,[1] and artist noted for his illustrated books.[2] His characteristic pen-and-ink drawings often depict vaguely unsettling narrative scenes in Victorian and Edwardian settings.

Edward St. John Gorey (February 22, 1925 – April 15, 2000) was an American writer, Tony Award-winning costume designer,[1] and artist noted for his illustrated books.[2] His characteristic pen-and-ink drawings often depict vaguely unsettling narrative scenes in Victorian and Edwardian settings.

Edward St. John Gorey was born in Chicago. His parents, Helen Dunham Garvey and Edward Leo Gorey,[3] divorced in 1936 when he was 11. His father remarried in 1952 when he was 27. His stepmother was Corinna Mura (1910–1965), a cabaret singer who had a small role in Casablanca as the woman playing the guitar while singing "La Marseillaise" at Rick's Café Américain. His father was briefly a journalist. Gorey's maternal great-grandmother, Helen St. John Garvey, was a nineteenth-century greeting card illustrator, from whom he claimed to have inherited his talents. From 1934 to 1937, Gorey attended public school in the Chicago suburb of Wilmette, Illinois, where his classmates included Charlton Heston, Warren MacKenzie, and Joan Mitchell.[4] Some of his earliest preserved work appears in the Stolp School yearbook for 1937.[5] After that, he attended the Francis W. Parker School in Chicago. He spent 1944 to 1946 in the Army at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah. He then attended Harvard University, beginning in 1946 and graduating in the class of 1950; he studied French and roomed with poet Frank O'Hara.[6]

Once at Harvard, the 20 years old Frank O'Hara kept the private screen around himself and though many began to sense he was different, no one called him out during his freshman or sophomore year. His Grafton friends came to realize that O'Hara had no sexual interest in girls, but the subject remained unmentioned. The O'Hara began to reveal himself under the friendship of Edward Gorey, who would later gain fame as a macabre illustrator. Another freshman veteran, Gorey was tall and dressed flamboyantly in black. Becoming roommates, they decorated their Eliot House suite with lawn furniture and a tombstone used as a table. Gorey often fell asleep in the living room after all-nighters spent designing wall paper and drawing ghoulish Edwardian cartoons using India ink. Some of O'Hara's music department friends thought that Gorey had corrupted him. O'Hara and Gorey were not lovers but they consciously adopted the highly stylized manners of an Oscar Wilde-era couple. A classmate in Eliot House, George Montgomery, later a photographer, remembers: "The first day Ted Gorey came into the Eliot House dining hall I thought he was the oddest person I'd ever seen... his hair plastered down across the front like bangs... He was wearing rings on his fingers. It was very, very faggoty." Perhaps that's why O'Hara in the fall of 1949 changed roommates (Gorey would later remark, "I have to admit I did feel mildly abandoned"). One of Gorey's greatest triumphs, for which he won a Tony, was designing the sets of Dracula, at the height of his fame in New York, where he too migrated, though never so happily as O'Hara and never to O'Hara's circle and only for so long.

In the early 1950s, Edward Gorey, with a group of recent Harvard alumni including Alison Lurie (1947), John Ashbery (1949), Donald Hall (1951) and Frank O'Hara (1950), amongst others, founded the Poets' Theatre in Cambridge, which was supported by Harvard faculty members John Ciardi and Thornton Wilder.[6][7][8] He frequently stated that his formal art training was "negligible"; Gorey studied art for one semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943.[9]

From 1953 to 1960, Gorey lived in Manhattan and worked for the Art Department of Doubleday Anchor, illustrating book covers and in some cases, adding illustrations to the text.[10] He illustrated works as diverse as Bram Stoker's Dracula, H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds,[11] and T. S. Eliot's Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats.[12] Throughout his career, he illustrated over 200 book covers for Doubleday Anchor, Random House's Looking Glass Library, Bobbs-Merrill, and as a freelance artist.[13] In later years he produced cover illustrations and interior artwork for many children's books by John Bellairs, as well as books begun by Bellairs and continued by Brad Strickland after Bellairs' death. His first independent work, The Unstrung Harp, was published in 1953. He also published under various pen names, some of which were anagrams of his first and last names, such as Ogdred Weary,[14] Dogear Wryde, Ms. Regera Dowdy, and dozens more. His books also feature the names Eduard Blutig ("Edward Gory"), a German-language pun on his own name, and O. Müde (German for O. Weary). At the prompting of Harry Stanton, an editor and vice president Addison-Wesley, Gorey collaborated on a number of works, and continued a lifelong correspondence with Peter F. Neumeyer.[15] The New York Times credits bookstore owner Andreas Brown and his store, the Gotham Book Mart, with launching Gorey's career: "it became the central clearing house for Mr. Gorey, presenting exhibitions of his work in the store's gallery and eventually turning him into an international celebrity."[16] Gorey's illustrated (and sometimes wordless) books, with their vaguely ominous air and ostensibly Victorian and Edwardian settings, have long had a cult following.[17] He made a notable impact on the world of theater with his designs for the 1977 Broadway revival of Dracula, for which he won the Tony Award for Best Costume Design and was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Scenic Design.[18] In 1980, Gorey became particularly well-known for his animated introduction to the PBS series Mystery! In the introduction of each Mystery! episode, host Vincent Price would welcome viewers to "Gorey Mansion".

Because of the settings and style of Gorey's work, many people have assumed he was British; in fact, he only left the U.S. once, for a visit to the Scottish Hebrides. Gorey settled in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod for half a year in 1963, fulltime in 1983 after the death of George Balanchine, whose every performance at the New York City Ballet Gorey had attended for years. In Yarmouth Port he wrote and directed numerous evening-length entertainments, often featuring his own papier-mâché puppets, an ensemble known as Le Theatricule Stoique. The first of these productions, Lost Shoelaces, premiered in Woods Hole, Massachusetts on August 13, 1987.[19] The last was The White Canoe: an Opera Seria for Hand Puppets, for which Gorey wrote the libretto, with a score by the composer Daniel James Wolf. Based on Thomas Moore's poem The Lake of the Dismal Swamp, the opera was staged after Gorey's death and directed by his friend, neighbor, and longtime collaborator Carol Verburg, with a puppet stage made by his friends and neighbors, the noted set designers Herbert Senn and Helen Pond. In the early 1970s, Gorey wrote an unproduced screenplay for a silent film, The Black Doll. After Gorey's death, one of his executors, Andreas Brown, turned up a large cache of unpublished work - complete and incomplete. Brown described the find as "ample material for many future books and for plays based on his work".[20]

Although Gorey's books were popular among children, he did not associate himself with children and had no particular fondness for them. Gorey never married, professed to have little interest in romance, and never discussed any specific romantic relationships in interviews. In Alexander Theroux's memoir of his friendship with Gorey, The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, published after Gorey's death, Theroux recalled that when Gorey was pressed on the matter of his sexual orientation. Theroux is referring to Lisa Solod's interview with Gorey ("Edward Gorey: The Cape's master teller of macabre tales discusses death, decadence, and homosexuality"), which appeared in the September 1980 issue of Boston magazine. In response to Solod's question, "What are your sexual preferences?" Gorey said: "Well, I'm neither one thing nor the other particularly. I suppose I'm gay. But I don't really identify with it much."[22] At which point, Solod notes that he laughed. Solod then asked, "Why not?" To which Gorey replied, "I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something. I do not spend my life picking up people on the streets. I was always reluctant to go to the movies with one of my friends because I always expected the police to come and haul him out of the loo at one point or the other. I know people who lead really outrageous lives. I've never said I was gay and I've never said I wasn't. A lot of people would say that I wasn't because I never do anything about it." Shortly thereafter, he said, "What I'm trying to say is that I am a person before I am anything else." Confusion and contention have arisen around the question of Gorey's sexuality for a number of reasons, chief among them is Gorey's general evasiveness in the face of any probing inquiry, by interviewers, into his inner life, especially his sexuality. But the omission of Gorey's remark "I suppose I'm gay" from the Solod interview when it appeared in Ascending Peculiarity,[23] a collection of interviews with Gorey edited by the art critic Karen Wilkin and overseen by Gorey's de facto business manager Andreas Brown, has also helped to cloud the question. Critic David Ehrenstein, writing in Gay City News, asserts that Gorey was discreet about his sexuality in what Ehrenstein calls the "Don’t Ask/ Don’t Tell era" of the 1950s. "Stonewall changed all that—making gay a discussable mainstream topic," writes Ehrenstein. "But it didn't change things for Gorey. To those in the know, his sensibility was clearly gay, but his sexual life was as covert as his self was overt."[24] By contrast, the critic Gabrielle Bellot argues that Gorey, "when pressed by interviewers about his sexuality ... declined to give clear answers, except during a 1980 conversation with Lisa Solod, wherein he claimed to be asexual—making Gorey one of few openly asexual writers even today."[25]

From 1995 to his death in April 2000, Gorey was the subject of a cinéma vérité–style documentary directed by Christopher Seufert. He was interviewed on Tribute to Edward Gorey, an hour-long community, public-access television cable show produced by artist and friend Joyce Kenney. He contributed his videos and personal thoughts. Gorey served as a judge at Yarmouth art shows and enjoyed activities at the local cable station, studying computer art and serving as cameraman on many Yarmouth shows. His house, in Yarmouthport, Cape Cod, is the subject of a photography book entitled Elephant House: Or, the Home of Edward Gorey, with photographs and text by Kevin McDermott. The house is now the Edward Gorey House Museum.[26] Gorey left the bulk of his estate to a charitable trust benefiting cats and dogs, as well as other species, including bats and insects.[20]

My published books: