Partner Paul Thévenaz, Walter Willard "Spud" Johnson, Clifford McCarthy, Robert Hunt

Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

Inn of the Turquoise Bear, 342 E Buena Vista St, Santa Fe, NM 87505, Stati Uniti

Harold

Witter Bynner, also known by the pen name Emanuel Morgan, (August 10, 1881

– June 1, 1968) was an American poet, writer and scholar, known for his

long residence in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and association with other

literary figures there.

Harold

Witter Bynner, also known by the pen name Emanuel Morgan, (August 10, 1881

– June 1, 1968) was an American poet, writer and scholar, known for his

long residence in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and association with other

literary figures there.

Bynner was born in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Thomas Edgarton Bynner and the former Annie Louise Brewer. His domineering mother separated from his alcoholic father in December 1888 and moved with her two sons to Connecticut. The father died in 1891, and in 1892 the family moved to Brookline, Massachusetts. Bynner attended Brookline High School and was editor of its literary magazine. He entered Harvard University in 1898, where he was the first member of his class invited to join the student literary magazine, The Advocate, by its editor Wallace Stevens. He was also published in another of Harvard's literary journals, The Harvard Monthly. His favorite professor was George Santayana. While a student he took on the nickname "Hal" by which his friends would know him for the rest of his life. He enjoyed theater, opera, and symphony performances in Boston, and he became involved in the suffrage movement. He graduated from Harvard with honors in 1902. His first book of poems, An Ode to Harvard (later changed to Young Harvard), came out in 1907.[1] In 1911 he was the Harvard Phi Beta Kappa Poet.[2]

After a trip to Europe, he took a position at McClure's Magazine and remained there for four years, meeting and socializing with many New York writers and artists. He then turned to independent writing and lecturing, living in Cornish, New Hampshire.[1]

In 1916 he was one of the perpetrators, with Arthur Davison Ficke, a friend from Harvard, of an elaborate literary hoax. It involved a purported "Spectrist" school of poets, along the lines of the Imagists, based in Pittsburgh. Spectra, a slim collection, was published under the pseudonyms of Anne Knish (Ficke) and Emanuel Morgan (Bynner). Marjorie Allen Seiffert, writing as Elijah Hay, was also part of the "movement".[3]

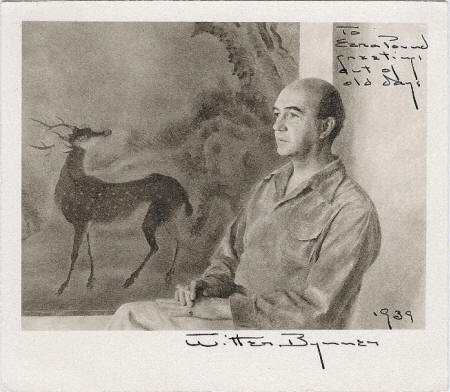

Title

Bynner, Witter,

Creator

Wyeth, Henriette

Inn of the Turquoise Bear

Bynner was friendly with Kahlil Gibran and introduced the writer to his publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, who went on to publish Gibran's The Prophet in 1923.[4] Gibran drew a portrait of Bynner in 1919.

In New York, Bynner was a member of The Players club, the Harvard Club, and the MacDowell Club. In San Francisco, he joined the Bohemian Club.[5]

Bynner traveled with Ficke and others to Japan, Korea and China in 1917.[6]

He had a short spell in academia in 1918–1919 at the University of California, Berkeley. He was hired to teach Oral English to the Students' Army Training Corps as a form of conscientious objector alternative service, and was invited to stay on in the English department after World War I ended to teach poetry. His students included several who became published poets of some note, such as Stanton A. Coblentz, Hildegarde Flanner, Idella Purnell, and Genevieve Taggard. In celebration of the end of the war, he composed A Canticle of Praise, performed in the Hearst Greek Theatre before some eight thousand people.[7] He met professor of Chinese Kiang Kang-hu and began an eleven-year collaboration with him on the translation of T'ang Dynasty poems. His teaching contract was not renewed, but his students continued to meet as a group and he occasionally joined them. An elaborate dinner honoring him was held at the Bohemian Club in San Francisco and a book of poems by students and friends, W.B. in California, was given to all who were present.[8]

It was during the Berkeley's years that Bynner met

Paul

Thévenaz.

It was Thévenaz’s irrepressible vitality

which first attracted Witter Bynner

Bynner traveled to China from June 1920 to April 1921 for intensive study of Chinese literature and culture.[1] He met sculptor Beniamino Bufano en route.[9] He returned to California and went to see family in New York, then embarked on another lecture tour, which took him to Santa Fe, New Mexico in February 1922. Exhausted and suffering from a lingering cold, he decided to cancel the rest of his tour and rest there.[1]

After another trip to Berkeley, where he enlisted his former student Walter Willard "Spud" Johnson to join him as his secretary (and lover), in June 1922 he moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Mabel Dodge Luhan introduced them to D.H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda, and Bynner and Johnson joined the Lawrences on a trip through Mexico in 1923. The trip led to several Lawrence essays and his novel The Plumed Serpent, including characters based on Bynner and Johnson. Bynner 's related writings include three poems about Lawrence, and Journey with Genius, a memoir published in 1951.[1]

Bynner’s open homosexuality, Myron Brinig and Cady Wells’ clandestine affair, and Agnes C. Sims and Mary Louise Aswell’s unabashed lesbian relationship, reveal the myriad of ways homosexuals who migrated to New Mexico understood and expressed their same-‐sex desires. Taos and Santa Fe artists and writers primarily organized communal life around their passion of artistic expression. They structured their artistic world upon discussion groups, social events, and community and political organizations. They also created avenues to explore their erotic identities such as “The Rabbles,” a group of poets including Alice Corbin, Witter Bynner, Haniel Long, Spud Johnson, and Lynn Riggs, which formed in the 1920s. The group, restricted to writers, met weekly at Corbin’s home. Johnson described the workshop group as a place where “we were all using it to try out new things, to get an advance reaction before sending things out into the bleak world of terse rejection slips; and as a stimulus to make us write when we might otherwise have fallen into the good old manaña spirit.” Group members stimulated, inspired, and critiqued each other’s poetry. They socialized together at dinner, read poetry aloud, and even played a sonnet writing game. Member Haniel Long recalled that the group “shared more than the artistic life” when they gathered together. The Rabble offered an arena “where people are valued for what they are” and fostered individuality. Riggs remembered later in life that “The Rabble” provided a forum for him to discover who he was. Riggs, Bynner, and Johnson all identified as homosexual and while it is difficult to ascertain if they wrestled with questions of desire during Rabble workshops, the cohort offered a gathering space to be oneself. This included wife and mother Alice Corbin who shunned feminine propriety in order to make “naughty cracks” that resulted in “infectious gurgles of laughter.” “The Rabble made us jolly-‐made us write,” concluded Johnson in a retrospective on the group’s heyday.

Bynner served as president of the Poetry Society of America from 1921 to 1923.[10] To encourage young poets, he created the Witter Bynner Prize for Undergraduate Excellence in Poetry, administered by the Poetry Society in cooperation with Palms poetry magazine, of which he was associate editor. Two recipients of the award were Countee Cullen in 1925 and Langston Hughes in 1926.

Bynner threw some parties just for queers while others contained a mix of straights and gays. According to Bronson Cutting’s biographer, the closeted gay politician, New Mexico Senator Cutting, attended Bynner’s respectable parties, but still managed to meet other gay men. At one such party, Cutting stole Bynner’s boyfriend, Clifford McCarthy (Don).

Mabel Dodge Luhan was not pleased about their trip, and she is said to have taken revenge on Bynner by hiring Johnson to be her own secretary. Bynner in turn wrote a play, Cake, satirizing her lifestyle. In 1930 Robert "Bob" Hunt arrived, originally for a visit while recuperating from an illness, but he stayed on as Bynner's lifelong companion. Together they entertained artists and literary figures such as D. H. Lawrence, Georgia O'Keeffe, Carl Sandburg, Ansel Adams, Willa Cather, Igor Stravinsky, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Robert Frost, W. H. Auden, Aldous Huxley, Christopher Isherwood, Carl Van Vechten, Martha Graham, and Thornton Wilder. They also made frequent visits to a second home in Chapala, Mexico.[1] The home was purchased from Mexican architect Luis Barragán. Bynner spent much of the 1940s and early 1950s there, until he began to lose his eyesight. He returned to the U.S., received treatment, and traveled to Europe with Hunt, who by the late 1950s and early 1960s took increasing responsibility for the ailing poet. Hunt died of a heart attack in January 1964.

In 1931, Bynner published Eden Tree a poetic musing about same-‐sex love inspired by his old love, Clifford McCarthy, and dedicated to a budding new romance with Robert Nicholas Montague Hunt. Bynner declared his homosexuality publicly, a rare and brave act, when he published Eden Tree.

On January 18, 1965, Bynner had a severe stroke. He never recovered, and required constant care until he died on June 1, 1968. Hunt and Bynner's ashes are buried beneath the carved stone weeping dog at the house where he lived on Atalaya Hill in Santa Fe, now used as the president's home for St. John's College.

My published books:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witter_Bynner