Wife Mary Garman

Queer Places:

Cemitério do São Pedro de Penaferrim

Sintra Municipality, Lisboa, Portugal

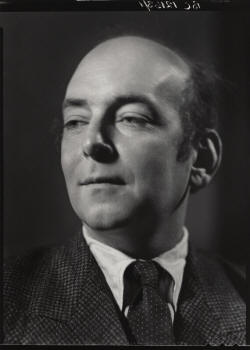

Ignatius Royston Dunnachie Campbell – better known as Roy Campbell (2 October 1901 – 23 April 1957) – was a South African poet and satirist of Scottish and Scotch-Irish descent.

Ignatius Royston Dunnachie Campbell – better known as Roy Campbell (2 October 1901 – 23 April 1957) – was a South African poet and satirist of Scottish and Scotch-Irish descent.

Born into a prominent family of White South Africans in Durban, Colony of Natal, Campbell was sent to the United Kingdom in the immediate aftermath of World War I. Although his family had intended for him to attend Oxford University, Campbell failed the entrance exam and drifted instead into London's literary bohemia. Following his cohabitation and marriage to English aristocrat-turned-bohemian Mary Garman, Campbell wrote the poem The Flaming Terrapin while staying with his wife in a converted stable near Aberdaron, in North Wales. Upon its publication, the poem was lavishly praised and brought the Campbell's easy entree into the highest circles of British literature. During a subsequent visit to his native South Africa, Campbell was first enthusiastically received. However, he then courted outrage in the literary magazine Voorslag by accusing his fellow White South Africans of racism, cultural backwardness, and of parasitism in their treatment of Black South Africans. In response, Campbell lost his job as editor and was subjected to social ostracism, even by his own family. Before returning to England with his family, Campbell retaliated by writing The Wayzgoose, a mock epic in the style of Alexander Pope and John Dryden, which skewered the racism and cultural backwardness of Colonial South Africa. In England, Roy and Mary Campbell were installed as guests on the estate of Vita Sackville-West and became involved with the Bloomsbury Group. Campbell ultimately learned, however, that his wife was engaged in a lesbian relationship with Vita, for whom Mary Campbell intended to leave him. Vita, however, was willing to continue the affair, but had no intention of entering the kind of monogamous relationship that Mary Campbell both desired and expected. At first, a heartbroken Campbell remained on the Sackville-West estate as the affair continued. After looking into the face of Vita's other lover, Virginia Woolf, Campbell saw his own suffering reflected back and fled to Provence. As her relationship with Vita crumbled, Mary joined him there and the spouses reconciled. Having decided that the Bloomsbury Group was snobbish, promiscuous, nihilistic, and anti-Christian, Campbell denounced them and their views in another verse satire inspired by Pope and Dryden, which he titled The Georgiad. Among British poets and intellectuals, however, Mary Campbell's affair with Vita was already common knowledge and The Georgiad was seen as a petty and vindictive attempt at revenge. Vita and the other targets of the satire were widely pitied and The Georgiad severely damaged Campbell's reputation.

,_Jacob_Kramer_&_Dolores.jpg)

Roy & Mary Campbell (left), Jacob Kramer & Dolores (right), 1920s

Roy and Mary Campbell's subsequent conversion to Roman Catholicism in Spain and the atrocities they witnessed by forces loyal to the Republic during the Spanish Civil War, caused the Campbell's to support Francisco Franco's Nationalists. In response, Campbell was labelled a Fascist by certain highly influential Left Wing poets, including Stephen Spender, Louis MacNeice, and Hugh MacDiarmid. After being evacuated from Spain to England, however, Campbell angrily rejected the efforts of Percy Wyndham Lewis, Sir Oswald Mosley, and William Joyce to recruit him into the British Union of Fascists, saying that he considered Fascism to be merely another form of Communism. Campbell then returned to Spain, where he travelled as a war correspondent alongside Franco's forces. In the process, Campbell was able to retrieve the personal papers of Saint John of the Cross, which he had hidden in his family's former flat in Republican-occupied Toledo and thus preserved for future scholars to examine. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Campbell returned to England and developed a close friendship with Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, which continued until Thomas's death. Also, despite being over-age and in very poor health, Campbell insisted upon enlisting in the British Army. While being trained for guerrilla warfare against the Imperial Japanese Army, Campbell was severely injured and ruled unfit for active service. After serving as a military censor and coast watcher in British East Africa, Campbell returned to the United Kingdom, where he befriended C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien and briefly became a member of The Inklings. In the post-war period, Campbell continued to write and translate poetry and to lecture worldwide. He also joined other White South African writers and intellectuals, including Laurens van der Post and Uys Krige, in denouncing Apartheid in his native South Africa. Campbell died in a car accident in Portugal on Easter Monday, 1957. Despite Campbell's decision to translate the poetry of Spanish Republican supporter Federico Garcia Lorca and his longstanding friendships with other supporters of the Spanish Republic such as Uys Krige and George Orwell, the accusation that Campbell was a Fascist, which was first promulgated during the 1930s, continues to seriously damage his reputation. For this reason, Campbell's verse continues to be left out of both poetry anthologies and University and college courses. Efforts have been made, however, by Peter Alexander, Joseph Pearce, Roger Scruton, Jorge Luis Borges, and other biographers and critics to rebuild Campbell's reputation and to restore his place in world literature. According to Roger Scruton, "Campbell wrote vigorous rhyming pentameters, into which he instilled the most prodigious array of images and the most intoxicating draft of life of any poet of the 20th century...He was also a swashbuckling adventurer and a dreamer of dreams. And his life and writings contain so many lessons about the British experience in the 20th century that it is worth revisiting them."[2] In a 2012 article for the Sunday Times, Tim Cartwright wrote, "Roy Campbell, in the opinion of most South African literary people, is still the best poet the country has ever produced."[3]

My published books: