Partner Vaslav Nijinsky

Queer Places:

Saint Petersburg State University, University Embankment, 7/9, Sankt-Peterburg, Russia, 199034

The Savoy, Strand, London WC2R 0EU, Regno Unito

Grand Hotel des Bains, Lungomare Guglielmo Marconi, 17, 30126 Venezia VE

Isola di San Michele, 30135 Venezia VE, Italia

Sergei

Pavlovich Diaghilev (31 March [O.S. 19 March] 1872 – 19 August 1929), usually

referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic,

patron, ballet impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes, from which many

famous dancers and choreographers would arise.

Sergei

Pavlovich Diaghilev (31 March [O.S. 19 March] 1872 – 19 August 1929), usually

referred to outside Russia as Serge Diaghilev, was a Russian art critic,

patron, ballet impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes, from which many

famous dancers and choreographers would arise.

Diaghilev's emotional life and the Ballets Russes were inextricably entwined. His most famous lover was Vaslav Nijinsky. However, according to Serge Lifar, of all Diaghilev's lovers, only Léonide Massine, who replaced Nijinsky, provided him with "so many moments of happiness or anguish."[10] Diaghilev's other lovers included Anton Dolin, Serge Lifar and his secretary and librettist Boris Kochno. Ironically, his last lover, composer and conductor Igor Markevitch later married the daughter of Nijinsky. They even named their son Vaslav.[11]

As a teenager, Diaghilev went on a grand tour with his cousin and lover Dmitry Filosofov (‘Dima’). As they made their way through Berlin, Paris, Venice, Rome, Florence and Vienna, their journey must have felt like nothing less than a honeymoon, given that they were in love with each other; and it is tempting to believe that Diaghilev’s lifelong restlessness, manifested particularly in his constant touring of Europe for both work and leisure, derived from the bliss of this first experience experience of international travel. Although he studied law in St Petersburg, and was awarded his law degree, he was constantly distracted by a greater interest in music. (He played the piano well, but Rimsky-Korsakov disabused him of the impression that he had a talent for composition.)

In 1898 Sergei Diaghilev toured Berlin, London and Paris, borrowing works of art to exhibit in St Petersburg. In Paris he sought out the exiled Oscar Wilde. Diaghilev was already a striking sight, tall and elegant, with an early white streak in his hair; the pair of them must have gone rather well together. Seeing them walking arm in arm, the women prostitutes are said to have stood on café chairs to hurl abuse at two such obvious threats to their business.

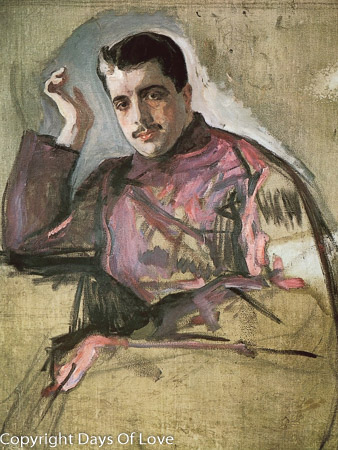

Portrait of Serge Diaghilev with His Nanny, by Léon Bakst (1906)

The Savoy, London

On 1 January 1899, Sergei Diaghilev started a cultural magazine, The World of Art (Mir Iskusstva), editing it fortnightly with Dima Filosofov. Simon Karlinsky calls the group of critics and artists behind the magazine ‘predominantly gay’; and it did, indeed, publish gay-related articles, such as an essay on the homosexual colony at Taormina by Zinaida Gippius.

When appointed Director of the Imperial Theatres in July 1899, Prince Sergei Mikhailovitch Volkonsky, who also happened to be gay, gave Diaghilev a job on the staff of the theatre directorate. It was when he was dismissed from this post, in 1901, that Diaghilev angrily went abroad, thereby unwittingly creating the conditions for the career in exile for which he is famous.

In the spring of 1906, Diaghilev went to Italy and Greece with his new lover, Alexis Mavrine. Later in the same year, he took his skill as an exhibitor, plus a consignment of Russian art, to Paris, where he set up L’Exposition de l’Art Russe at the Salon d’Automne. He gained his first entrée to French society when he met Élisabeth, Countess Greffulhe, the model for Marcel Proust’s Princesse de Guermantes.

Sergei Diaghilev thought very highly of Mikhail Kuzmin’s work. They saw so much of each other for a short time in 1907 that Kuzmin noted in his diary: ‘Gossip is making the rounds about me and Diaghilev. Quel farce’ (31 October 1907).

Not willing to confine his skills to a single art, Diaghilev began to organise a series of concerts of Russian music, where possible to be conducted by the composers themselves. Five such concerts were staged in May 1907. Following on from the success of these, he quickly thought of staging an opera season for 1908. Thus, in due course, Boris Godunov opened in Paris on 19 May 1908, with Feodor Chaliapin as Boris. Diaghilev’s next project was to bring the Imperial Ballet to Paris.

In May 1909, the various opera and ballet artists travelled down from Russia to France. At this time Diaghilev was gradually turning his emotional attention away from Alexis Mavrine, who was travelling as his secretary, to Vaslav Nijinsky, to whom he had been introduced by Nijinsky’s then lover Prince Pavel Dmitrievitch Lvov the previous autumn. On 18 May, the ballet’s season opened at the Châtelet. A day or two later, Mavrine eloped with the ballerina Olga Feodorova, leaving Diaghilev fuming with anger but free to concentrate on his new love interest. The ballerina Tamara Karsavina remarked that ‘Diaghilev had become overnight a leader of the Paris homosexual set’, by which she meant the circle that included Lucien Daudet, Reynaldo Hahn, Marcel Proust and Jean Cocteau. The season ended in mid-June, with the company deeply in debt and Diaghilev a declared bankrupt.

When Nijinsky fell ill at the end of the season, Diaghilev rented a small flat and nursed him there himself. In August the two of them joined the designer Léon Bakst in Venice; then they travelled back to St Petersburg via Paris. Diaghilev commissioned The Firebird from Igor Stravinsky, hoping that Anna Pavlova would dance the title role.

The Ballets Russes opened their 1910 season on 20 May in Berlin, or rather at the Theater des Westens in the suburb of Charlottenburg; and they opened in Paris on 4 June. It was then that Marcel Proust said of their performance of Rimsky’s Schéhérazade, ‘I never saw anything so beautiful’. As it happened, Anna Pavlova turned out to be unavailable for The Firebird, so it was premiered on 25 June with Tamara Karsavina in the lead role. Because Diaghilev had not brought a Russian orchestra on this second season in Paris and was not having to pay Chaliapin and an opera company, the season proved financially secure.

On 5 February 1911, Nijinsky danced the male lead in Giselle without wearing trunks over his tights and was dismissed from the Imperial Ballet. When he and Nijinsky left Russia in mid-March, the latter was leaving for good. On 9 April they opened their season in Monte Carlo. After Rome (from 14 May), the Paris season opened on 6 June. Nijinsky danced in Carnaval, Narcisse and Le Spectre de la rose, and as the puppet in Petrushka. (When rehearsals of Petrushka began, the orchestra thought Igor Stravinsky’s score was a joke.) The company opened its London season on 21 June 1911 at Covent Garden, where they were astonished to find themselves in the middle of a vegetable market. The city was packed for the Coronation of George V on 22 June. The King and Queen themselves attended the ballet on the 24th. While in London, Nijinsky went round to John Singer Sargent’s studio in Tite Street, Chelsea, and Sargent sketched his head.

January 1912 saw the company in Berlin; May in Paris again. Nijinsky appeared with his skin painted blue in Le Dieu bleu, an Orientalist collaboration between Jean Cocteau and Reynaldo Hahn, designed by Léon Bakst. The first performance of Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloë was staged on 8 June, with Nijinsky as Daphnis. At a tense final rehearsal, the choreographer Michel Fokine, who was currently falling out of favour, called Diaghilev a bugger in front of the whole company.

Another Covent Garden season was staged between mid-July and the beginning of August. On this London trip Nijinsky and Léon Bakst went to tea with Ottoline Morrell in Bedford Square and watched Duncan Grant playing tennis with a group of his friends. It is quite likely that this afternoon in Bloomsbury provided the initial inspiration for what was to become the ballet Jeux, premiered at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris on 15 May 1913. Nijinsky’s diary is revealing about this piece: the story of this ballet is about three young men making love to each other … Jeux is the life of which Diaghilev dreamed. He wanted to have two boys as lovers. He often told me so, but I refused. Diaghilev wanted to make love to two boys at the same time, and wanted these boys to make love to him. In the ballet, the two girls represent the two boys and the young man is Diaghilev. I changed the characters, as love between three men could not be represented on the stage. Even with the sexes normalised, a substantial part of the audience was inclined to laugh at a ballet based on a game of tennis.

Notwithstanding the flashy surprises of Jeux, the real coup of the 1913 season was, of course, the première, on 29 May, of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps). It was followed by Nijinsky in Le Spectre de la rose, and the evening ended with Prince Igor.

In mid-August, Diaghilev sent the company off on a South American tour, remaining in Europe himself. By the time they disembarked in Rio de Janeiro, Nijinsky was engaged to Romola de Pulszky. (He first met her in Vienna, earlier in the year, and she had been following him ever since.) They got married on 10 September in Buenos Aires. Romola became pregnant in Rio on the way home. When Diaghilev heard the news, he angrily took himself off to Naples for a holiday. By the end of the year, he had sacked Nijinsky. Seeking a replacement, his eye and instinct lit on an eighteen-year-old called Léonide Miassin, who later changed his name to Massine. Diaghilev soon developed an attachment to the boy; in August 1914 he took him on a long holiday in Italy – one of his most familiar modes of courtship – and although Léonide was heterosexual, they developed an understanding that encompassed both their personal friendship and the working relationship. In Florence, Diaghilev persuaded Léonide, who had never considered such a thing, to become a choreographer. Diaghilev rented a house at Ouchy on the north shore of Lake Geneva, within cycling distance of where Igor Stravinsky was living (the latter’s cycling distance, of course, not Diaghilev’s own). Here, he restructured his company and had the sense to re-engage Nijinsky.

Nijinsky appeared again with the company, but the old relationship between the men was never re-established; moreover, Nijinsky's magic as a dancer was much diminished by incipient madness. Their last meeting was after Nijinsky's mind had given way, and he appeared not to recognise his former lover. On April 12, 1916, in New York, Nijinsky danced Petrushka and Le Spectre de la rose. He was not well received by the Americans: both the Herald and the Times called him ‘effeminate’; and indeed, when he appeared in Narcisse on the 22nd, some sections of the audience laughed at him and the Herald excelled itself by calling him ‘offensively effeminate’.

Diaghilev was known as a hard, demanding, even frightening taskmaster. Ninette de Valois, no shrinking violet, said she was too afraid to ever look him in the face. George Balanchine said he carried around a cane during rehearsals, and banged it angrily when he was displeased. Other dancers said he would shoot them down with one look, or a cold comment. On the other hand, he was capable of great kindness, and when stranded with his bankrupt company in Spain during the 1914–18 war, gave his last bit of cash to Lydia Sokolova to buy medical care for her daughter. Alicia Markova was very young when she joined the Ballet Russes and would later say that she had called Diaghilev "Sergypops" and he had said he would take care of her like a daughter.

Dancers such as Alicia Markova, Tamara Karsavina, Serge Lifar, and Lydia Sokolova remembered Diaghilev fondly, as a stern but kind father-figure who put the needs of his dancers and company above his own. He lived from paycheck to paycheck to finance his company, and though he spent considerable amounts of money on a splendid collection of rare books at the end of his life, many people noticed that his impeccably cut suits had frayed cuffs and trouser-ends. The film The Red Shoes is a thinly disguised dramatization of the Ballet Russes.

Back in Paris, Diaghilev met Picasso for the first time. Soon afterwards, Picasso agreed to work with Eric Satie and Jean Cocteau on Parade. When the company sailed back to the States in the autumn, Diaghilev put Nijinsky in charge of the tour and went to Rome with Léonide Massine. Picasso and Cocteau joined him there in February 1917 to work on Parade. When Diaghilev took Massine down to Naples in the spring and he took a fancy to I Galli, a little cluster of rocky islands off the Sorrentine peninsula, Diaghilev set his heart on buying them some day. (This would prove complicated, since they belonged to different members of one extensive family.) Parade was given its première in Paris on 18 May.

The following month the company was in Madrid, where the King and Queen attended every one of their performances. Diaghilev and Massine had made friends with Manuel de Falla; they suggested he turn his incidental music to The Three-Cornered Hat (El Sombrero de tres picos) into a ballet. (It would have its first performance at the Alhambra in Leicester Square, London, on 22 July 1919.) Relations between Diaghilev, Léonide Massine and Nijinsky were unusually peaceable until the moment when the latter, supported by his wife, announced that he would not be going on the forthcoming tour of South America. In the event, Nijinsky did go but Diaghilev stayed behind. So a performance at the Teatro Liceo in Barcelona on 30 June 1917 was the last time Diaghilev ever saw Nijinsky dance. At the end of the South American tour, Nijinsky stayed behind in Buenos Aires when the company left for Europe. A single performance he gave as a benefit for the Red Cross in Montevideo was the last occasion he ever danced in public.

When the Armistice was announced on 11 November 1918, Diaghilev and Léonide Massine were dining with Osbert Sitwell in London. They made their way through the crowds in Trafalgar Square to a party at the Adelphi, off the Strand. Here, in Massine’s words, they found that ‘the Bloomsbury Junta was in full session’. Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Roger Fry, D.H. Lawrence, Mark Gertler, Ottoline Morrell, David Garnett, Duncan Grant and John Maynard Keynes were all there; everyone except Diaghilev was dancing.

Diaghilev travelled with Massine many times in the ensuing months. They holidayed together in Naples and Venice in the summer of 1920. But the following January, Diaghilev sacked Massine for having a heterosexual affair within the company. At the end of February, Diaghilev took on Boris Kochno, a teenager, as his secretary. Although the boy was disappointed not to become his employer’s lover as well, Diaghilev did look after him and their increasingly intimate relationship soon became indispensable to both of them. In 1923 another youngster arrived on the scene, materialising in Paris from Russia. He was the eighteen-year-old dancer Serge Lifar. According to Richard Buckle, ‘He was (by his own admission) sexless, feeling no physical desire either for men or women, although he aroused the desire and love of both’.

Next in line, as both dancer and lover, was Patrick Healey-Kay, otherwise known as Anton Dolin. As they travelled down to Monte Carlo, Diaghilev moved him into his sleeping compartment: ‘Patrick, as Diaghilev always called him, understood the ways of the world. He had been seduced by a priest in the confessional when he was a boy.’ Aptly, the new ballet Le Train bleu was created for Dolin. When they were in Venice, ‘Patrick enjoyed himself on the beach [at the Lido], and Diaghilev occasionally interrupted his dipping into Proust and Radiguet to watch him through binoculars.’ Mind you, Boris Kochno claimed Diaghilev never really read, but only ‘counted the pages’. Dolin was disappointed to receive a copy of Death in Venice from the older man for his twentieth birthday in July 1924; but in the evening a Cartier gold watch was added to the gift. Dolin left the company in June 1925, by which time Diaghilev was living with Serge Lifar.

In the spring of 1928, Rupert Doone turned down the chance to tour as Anna Pavlova’s partner; but this left him free, in July of the following year, to accept an invitation to join Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes as a soloist.

In the summer of 1928, at the age of fifty-six, Diaghilev, who had been diagnosed with diabetes in June, fell in love with the sixteen-year-old composer Igor Markevich, who was to become his last protégé. Although Markevich was heterosexual – he would later marry Nijinsky’s daughter, Kyra – he liked Diaghilev’s company and was flattered by his affection. After a holiday with Markevich in Germany, Diaghilev went down to the Hôtel des Bains de Mer on the Lido at Venice and invited Serge Lifar to join him there. The pace of life was catching up with him. Lifar nursed him alone until Boris Kochno was called down from Toulon. The increasingly tired and weak Diaghilev was still euphoric about the successful holiday with Markevich, and whenever Lifar was out of the room he would share with Kochno the details of that last idyll. The two acolytes watched over him through his last days and were present when he died.

Throughout his life, Diaghilev was severely afraid of dying in water, and avoided traveling by boat. He died of diabetes[12] in Venice on 19 August 1929, and is buried on the nearby island of San Michele, near to the grave of Stravinsky, in the Orthodox section.[13]

The Ekstrom Collection of the Diaghilev and Stravinsky Foundation is held by the Department of Theatre and Performance of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[14]

My published books: