Partner Katherine Laird Cox, Cathleen Nesbitt, Noel Olivier

Queer Places:

5 Hillmorton Rd, Rugby CV22 5DF, Regno Unito

46 Dean Park Rd, Bournemouth BH1 1QA, Regno Unito

Rugby School, Lawrence Sheriff St, Rugby CV22 5EH, Regno Unito

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

St Andrew and St Mary, Grantchester, Cambridge, Regno Unito

Westminster Abbey, 20 Deans Yd, Westminster, London SW1P 3PA, Regno Unito

Skyros, Skiros 340 07, Grecia

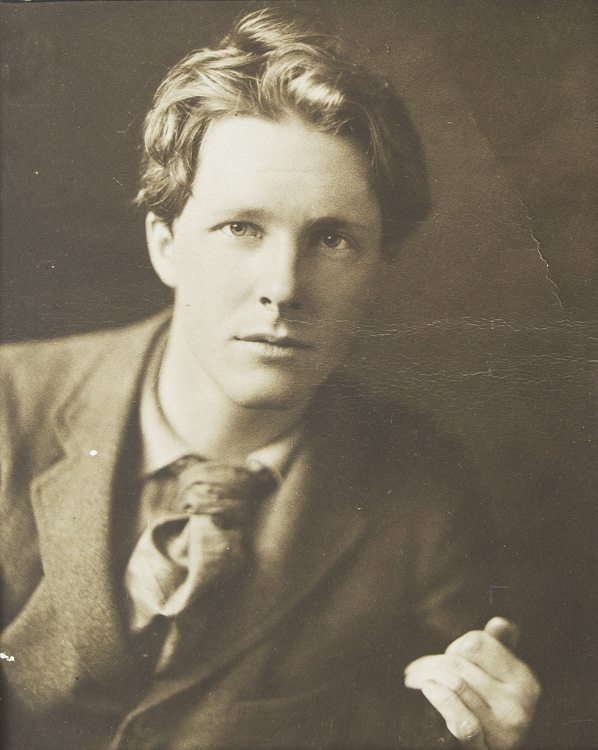

Rupert Chawner Brooke (middle name sometimes given as "Chaucer;"[1]

3 August 1887 – 23 April 1915[2])

was an English poet known for his idealistic war sonnets written during the

First World War, especially "The Soldier.” Identified with the

Lost Generation. He was part of

the Cambridge Apostles. He was also known for his boyish

good looks, which were said to have prompted the Irish poet W. B. Yeats to

describe him as "the handsomest young man in England.”[3][4]

Rupert Chawner Brooke (middle name sometimes given as "Chaucer;"[1]

3 August 1887 – 23 April 1915[2])

was an English poet known for his idealistic war sonnets written during the

First World War, especially "The Soldier.” Identified with the

Lost Generation. He was part of

the Cambridge Apostles. He was also known for his boyish

good looks, which were said to have prompted the Irish poet W. B. Yeats to

describe him as "the handsomest young man in England.”[3][4]

Rupert Brooke was closer to a group of friends, who Virginia Woolf called the ‘neo-pagans’, possibly due to their love of the outdoors. This group included Rupert Brooke, Ethel Pye, Katherine Cox, the Olivier sisters (Brynhild Olivier, Noël Oliveri, Margery Oliver and Daphne Oliver), Jacques and Gwen Raverat, Frances Cornford and Justin Brooke. Despite sharing the same surname, Justin Brooke was not a relative of Rupert’s.

Brooke was born at 5 Hillmorton Road, Rugby, Warwickshire,[5][6] the second of the three sons of William Parker Brooke, a schoolmaster (teacher) at one of England's most prestigious schools, and his wife Ruth Mary Brooke, née Cotterill. He attended preparatory (prep) school locally at Hillbrow, and then went on to Rugby itself. In 1905, he became friends with St. John Lucas, who thereafter became something of a mentor to him.[7]

While travelling in Europe he prepared a thesis, entitled "John Webster and the Elizabethan Drama", which won him a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge. There he became a member of the Apostles, was elected as President of the Fabian Society, helped found the Marlowe Society drama club and acted, including the Greek Play. The friendships he made at school and university set the course for his adult life, and many of the people he met - including for example George Mallory - fell under his spell.[8] Virginia Woolf boasted to Vita Sackville-West of once going skinny-dipping with Brooke in a moonlit pool when they were in Cambridge together.[9]

5 Hillmorton Rd, Rugby

Rugby School

Westminster Abbey, London

Brooke made friends among the Bloomsbury group of writers, some of whom admired his talent while others were more impressed by his good looks. He also belonged to another literary group known as the Georgian Poets and was one of the most important of the Dymock poets, associated with the Gloucestershire village of Dymock where he spent some time before the war. He also lived in the Old Vicarage, Grantchester, which stimulated one of his best-known poems, named after the house, written with homesickness while in Berlin in 1912.

Brooke suffered a severe emotional crisis in 1912, caused by sexual confusion (he was bisexual)[10] and jealousy, resulting in the breakdown of his long relationship with Ka Cox (Katherine Laird Cox).[11] Brooke's paranoia that Lytton Strachey had schemed to destroy his relationship with Cox by encouraging her to see Henry Lamb precipitated his break with his Bloomsbury group friends and played a part in his nervous collapse and subsequent rehabilitation trips to Germany.[12]

As part of his recuperation, Brooke toured the United States and Canada to write travel diaries for the Westminster Gazette. He took the long way home, sailing across the Pacific and staying some months in the South Seas. Much later it was revealed that he may have fathered a daughter with a Tahitian woman named Taatamata with whom he seems to have enjoyed his most complete emotional relationship.[13][14] Many more people were in love with him.[15] Brooke was romantically involved with the artist Phyllis Gardner and the actress Cathleen Nesbitt, and was once engaged to Noel Olivier, whom he met, when she was aged 15, at the progressive Bedales School.

Brooke enlisted at the outbreak of war in August 1914. He came to public attention as a war poet early the following year, when The Times Literary Supplement quoted two of his five sonnets ("IV: The Dead" and "V: The Soldier") in full on 11 March; the latter was then read from the pulpit of St Paul's Cathedral on Easter Sunday (4 April). Brooke's most famous collection of poetry, containing all five sonnets, 1914 & Other Poems, was first published in May 1915 and, in testament to his popularity, ran to 11 further impressions that year and by June 1918 had reached its 24th impression;[16] a process undoubtedly fuelled through posthumous interest.

Brooke's accomplished poetry gained many enthusiasts and followers, and he was taken up by Edward Marsh, who brought him to the attention of Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. Brooke was commissioned into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a temporary Sub-Lieutenant[17] shortly after his 27th birthday and took part in the Royal Naval Division's Antwerp expedition in October 1914.

Brooke sailed with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on 28 February 1915 but developed sepsis from an infected mosquito bite. He died at 4:46 pm on 23 April 1915, on the French hospital ship, the Duguay-Trouin, moored in a bay off the Greek island of Skyros in the Aegean Sea, while on his way to the landing at Gallipoli. As the expeditionary force had orders to depart immediately, Brooke was buried at 11 pm in an olive grove on Skyros.[1][2][18] The site was chosen by his close friend, William Denis Browne, who wrote of Brooke's death:[19]

I sat with Rupert. At 4 o’clock he became weaker, and at 4.46 he died, with the sun shining all round his cabin, and the cool sea-breeze blowing through the door and the shaded windows. No one could have wished for a quieter or a calmer end than in that lovely bay, shielded by the mountains and fragrant with sage and thyme.

His grave remains there still, with monument erected by his friend Stanley Casson,[20] poet and archaeologist, who in 1921 published Rupert Brooke and Skyros, a "quiet essay", illustrated with woodcuts by Phyllis Gardner[21] Another friend and war poet, Patrick Shaw-Stewart, assisted at his hurried funeral.[22]

On 11 November 1985, Brooke was among 16 First World War poets commemorated on a slate monument unveiled in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey.[23] The inscription on the stone was written by a fellow war poet, Wilfred Owen. It reads: "My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity."[24]

The wooden cross that marked Brooke's grave on Skyros, which was painted and carved with his name, was removed when a permanent memorial was made there. His mother, Mary Ruth Brooke, had the cross brought to Rugby, to the family plot at Clifton Road Cemetery. Because of erosion in the open air, it was removed from the cemetery in 2008, and replaced by a more permanent marker. The Skyros cross is now at Rugby School with the memorials of other old Rugbeians.[25]

Brooke's surviving brother, 2nd Lt. William Alfred Cotterill Brooke, was a member of the 8th Battalion London Regiment (Post Office Rifles) and was killed in action near Le Rutoire Farm on 14 June 1915 aged 24. He is buried in Fosse 7 Military Cemetery (Quality Street), Mazingarbe, Pas de Calais, France. He had only joined the battalion on 25 May.[26]

The first stanza of The Dead is inscribed onto the base of the Royal Naval Division War Memorial in London.[27]

American adventurer Richard Halliburton made preparations towards writing a biography of Brooke, meeting his mother and others who had known the poet, and corresponding widely and collecting copious notes, but he too died young, the manuscript unwritten.[28] Halliburton's notes were used by Arthur Springer to write Red Wine of Youth—A Biography of Rupert Brooke (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952).[29]

My published books: