Queer Places:

7 Berkeley Square, Bristol

Harrow School, 5 High St, Harrow HA1 3HP, Regno Unito

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

Clifton Hill House, Lower Clifton Hill, Bristol BS8 1BX, Regno Unito

Am Hof, Davos-Platz, 7270 Davos

Campo Cestio, Via Caio Cestio, 6, 00153 Roma RM, Italia

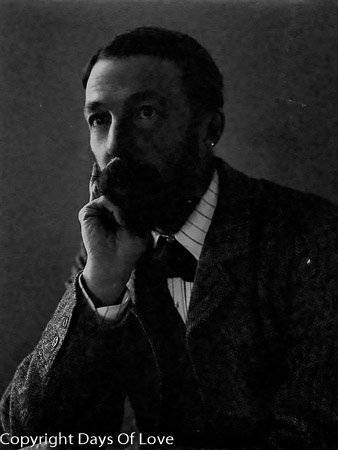

John

Addington Symonds (5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and

literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the

Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although

he married and had a family, he was an early advocate of male love

(homosexuality), which he believed could include pederastic as well as

egalitarian relationships, referring to it as l'amour de l'impossible

(love of the impossible).[1]

He also wrote much poetry inspired by his homosexual affairs. As a young man,

Symonds locked his early poems in a black tin box, then gave the key to

his friend Henry Sidgwick, who threw

it into the river Avon. After his death,

Edmund Gosse and the

librarian of the London Library organized

John Addington Symonds’ papers into a pile in the library garden and set

fire to them. What Cannot Be (1861), Eudiades (1868), Midnight at Baiae (c. 1875), Stella Maris XLV (1881-82) and A Problem in Modern Ethics (1891)

are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade.

John

Addington Symonds (5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and

literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the

Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although

he married and had a family, he was an early advocate of male love

(homosexuality), which he believed could include pederastic as well as

egalitarian relationships, referring to it as l'amour de l'impossible

(love of the impossible).[1]

He also wrote much poetry inspired by his homosexual affairs. As a young man,

Symonds locked his early poems in a black tin box, then gave the key to

his friend Henry Sidgwick, who threw

it into the river Avon. After his death,

Edmund Gosse and the

librarian of the London Library organized

John Addington Symonds’ papers into a pile in the library garden and set

fire to them. What Cannot Be (1861), Eudiades (1868), Midnight at Baiae (c. 1875), Stella Maris XLV (1881-82) and A Problem in Modern Ethics (1891)

are cited as examples in Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English

Literature from 1850-1900, by Brian Reade.

In spring of 1858, Symonds fell in love with William Fear Dyer, a Bristol choirboy three years younger. They engaged in a chaste love affair that lasted a year, until broken up by Symonds. The friendship continued for several years afterwards, until at least 1864. Dyer became organist and choirmaster of St Nicholas' Church, Bristol. In the autumn of 1858, Symonds went to Balliol College, Oxford, as a commoner but was elected to an exhibition in the following year.

When John Addington Symonds first arrived in Oxford, his friends included Edward William Urquhart, who, he reports, “had high church proclivities and ran after Choristers.” His friend Randell Vickers was “a man of somewhat similar stamp.” “In their company,” he notes, “I frequented antechapels and wasted my time over feverish sentimentalism”. Symonds also became “intimate friends” at Oxford with Charles Shorting, a friendship terminated when the latter’s “conduct with regard to boys, especially the choristers at Magdalen, brought him into serious trouble”. Symonds later blamed Shorting for bringing his “peculiar atmosphere of boy-love into [his] neighbourhood” around 1862.

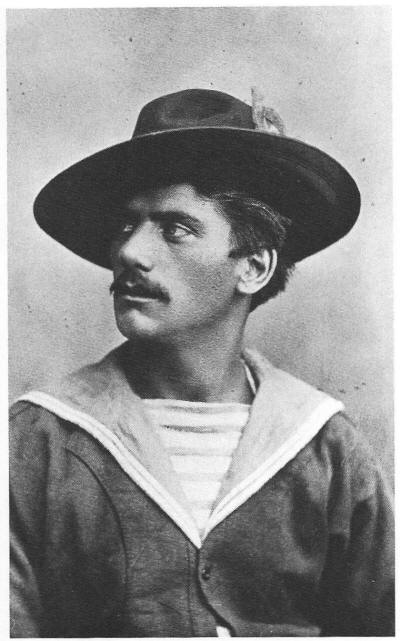

Angelo Fusato

Augusto Zanon, 20, Symond’s Venetian porter, 1890.

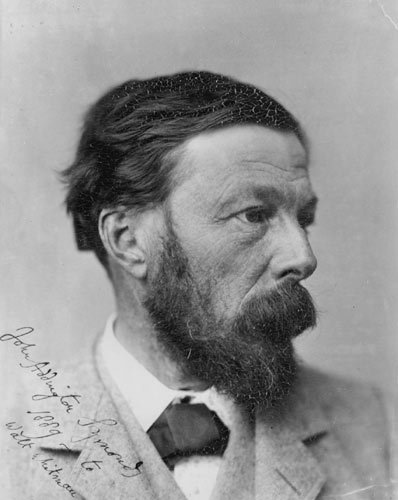

John Addington Sumonds, 1889, signed to Walt Whitman

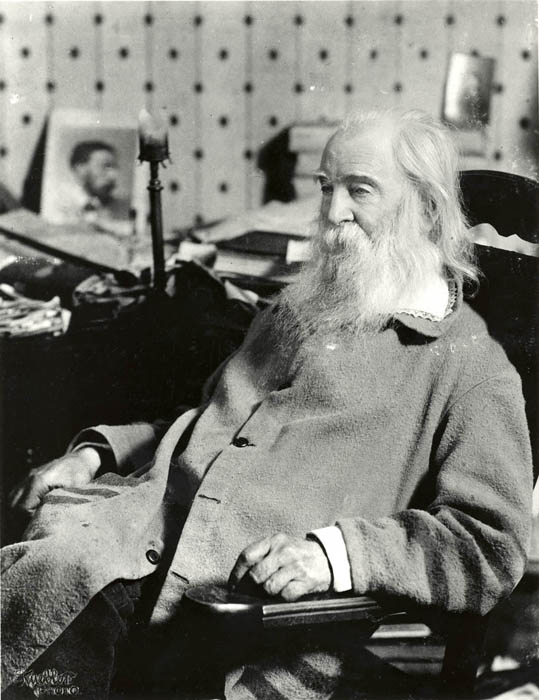

Walt Whitman with Symonds' photo on the desk

Clifton Hill House, Bristol

At Oxford John Addington Symonds met Claude Delaval Cobham, another student, who in 1861 professed himself "an anderastes" (probably something like "man enthusiast") and remained one for the rest of his life. Symonds knew that Cobham had "a passion for soldiers," and enjoyed "the most licentious pleasures to which two men can yield themselves". Cobham's imagination "was steeped in a male element of lust," and he "disliked women." But in all other ways said Symonds, Cobham was "sympathetic, warm-hearted, ready to serve his friends, successful in society, cheerful, and not devoid of remarkable intellectual gifts.

John Conington, a "scrupulously moral" professor, sympathized "with romantic attachments for boys." He gave Symonds a volume of verse by William Johnson that told the "love story" of the author, an Eton master, and the "pretty" Charlie Wood of Christ Church, who had been his pupil. In early 1858, Alfred Pretor, a friend of John Addington Symonds, sent him a letter, telling him that he was having an affair with Charles Vaughan, headmaster of Harrow School, and showed him several love letters. Symonds did not mention the incident for over a year, and then in 1859, gave the whole story to John Conington. Conington told Symonds to tell his father John Addington Symonds, a doctor. Symonds senior wrote to Vaughan to inform him that he knew of his behaviour with Pretor. He would not expose him publicly, as long as Vaughan agreed to resign at once.

At Oxford in 1861, John Addington Symonds fell "violently in love with a cathedral chorister," Alfred or Arthur Brooke, a "passion" Symonds experienced as "more intense, unreasonable, poignant," and "sensual" than his feeling for Willie Dyer. Brooke had "the most beautiful face I ever saw and the most faschinating voice I ever heard." His passion for the seductive Brooke made it more difficult for Symonds to resist acting upon his sexual impulses, but resist he did. The two exchanged not a single kiss. In November 1862, a vindictive Charles Shorting, publicly charged Symonds with having earlier supported Shorting's pursuit of a choirboy and with sharing Shorting's interest in choristers. A month later, at a general meeting of the college, Symonds received a "complete acquittal," though two of his letters to Shorting were "strongly condemned."

John Addington Symonds had studied Walt Whitman's poems carefully when, in February 1867, he wrote a "secret letter" to his close friend and confidant, Henry Graham Dakyns, a classicist and professor at Clifton College. If only Symonds had read Leaves of Grass earlier, he said, "I should have been a braver better very different man now." Leaves of Grass was "not a book," he exclaimed, "it is a man, miraculous in his vigour & love... & animalisme & onnivorous humanity." Symonds began corresponding with Whitman in 1871. His most famous letter was written in August of 1890 wherein, after years of indirect questioning, Symonds directly asked Whitman about the homosexual content of the "Calamus" poems. Symonds spent 20 years in correspondence trying to pry the answer from him.[132] In 1890 he wrote to Whitman, "In your conception of Comradeship, do you contemplate the possible intrusion of those semi-sexual emotions and actions which no doubt do occur between men?" In reply, Whitman denied that his work had any such implication, asserting "[T]hat the calamus part has even allow'd the possibility of such construction as mention'd is terrible—I am fain to hope the pages themselves are not to be even mention'd for such gratuitous and quite at this time entirely undream'd & unreck'd possibility of morbid inferences—wh' are disavow'd by me and seem damnable," and insisting that he had fathered six illegitimate children. Some contemporary scholars are skeptical of the veracity of Whitman's denial or the existence of the children he claimed.[133]

While in Clifton in 1868, John Addington Symonds met and fell in love with Norman Moor, a youth about to go up to Oxford, who became his pupil.[5] Symonds and Moor had a four-year affair but did not have sex.[6] According to Symonds' diary of 28 January 1870, "I stripped him naked and fed sight, touch and mouth on these things."[7] The relationship occupied a good part of his time. (On one occasion he left his family and travelled to Italy and Switzerland with Moor.[8]) It also inspired his most productive period of writing poetry, published in 1880 as New and Old: A Volume of Verse.[9] In December 1878, Edward Norman Peter Moor married Emily S. Powell, a vicar’s daughter two years his senior. The pair lived initially at Cecil Road, but made their married home in Northcote Road, close to Clifton College where Moor taught as assistant Master. Symonds spent that winter at Davos, but received visits that month from two other former Clifton students: Horatio F. Brown and Hugh Pearson. In a later letter to Henry Graham Dakyns he noted “I fancy you think of Mrs E. N. P. Moor? I don’t care for her photograph.”[23]

In 1873, Symonds wrote A Problem in Greek Ethics, a work of what would later be called "gay history." He was inspired by the poetry of Walt Whitman, with whom he corresponded.[11] The work, "perhaps the most exhaustive eulogy of Greek love,"[12] remained unpublished for a decade, and then was printed at first only in a limited edition of 10 copies for private distribution.[13] Although the Oxford English Dictionary credits the medical writer C.G. Chaddock for introducing "homosexual" into the English language in 1892, Symonds had already used the word in A Problem in Greek Ethics.[14] Aware of the taboo nature of his subject matter, Symonds referred obliquely to pederasty as "that unmentionable custom" in a letter to a prospective reader of the book,[15] but defined "Greek love" in the essay itself as "a passionate and enthusiastic attachment subsisting between man and youth, recognised by society and protected by opinion, which, though it was not free from sensuality, did not degenerate into mere licentiousness."[16]

Seeking a climate that would slow the advance of his tubercolosis, John Addington Symonds and his family moved in August 1877 to Davos Platz, Switzerland. Four months after arriving in Switzerland, Symonds met Christian Buol, a 19 year-old from a financially strapped, "very ancient noble family." They gradually established what Symonds called a "sensual spiritual" intimacy, a relationship that continued for more than a dozen years after Buol was married. In 1878, Symonds took the young man on a trip to Italy during which, Symonds' Memoirs report, "We often slept together in the same bed," and Buol "was not shy of allowing me to view... the naked splendor of his perfect body."

Symonds studied classics under Benjamin Jowett at Balliol College, Oxford, and later worked with Jowett on an English translation of Plato's Symposium.[17] Jowett was critical of Symonds' opinions on sexuality,[18] but when Symonds was falsely accused of corrupting choirboys, Jowett supported him, despite his own equivocal views of the relation of Hellenism to contemporary legal and social issues that affected homosexuals.[19]

Symonds also translated classical poetry on homoerotic themes, and wrote poems drawing on ancient Greek imagery and language such as Eudiades, which has been called "the most famous of his homoerotic poems".[17] While the taboos of Victorian England prevented Symonds from speaking openly about homosexuality, his works published for a general audience contained strong implications and some of the first direct references to male-male sexual love in English literature. For example, in "The Meeting of David and Jonathan", from 1878, Jonathan takes David "In his arms of strength / [and] in that kiss / Soul into soul was knit and bliss to bliss". The same year, his translations of Michelangelo's sonnets to the painter's beloved Tommaso Cavalieri restore the male pronouns which had been made female by previous editors. In November 2016, Symonds' homoerotic poem, 'The Song of the Swimmer', written in 1867, was published for the first time in the Times Literary Supplement.[20]

In 1881 in Venice, John Addington Symonds met a "strikingly handsome" gondolier, Angelo Fusato, for whom he felt "love at first sight." Venetian gondoliers, Symonds learned later, were "so accustomed" to the sexual propositions of travelers "that they think little of gratifying the caprice of ephemeral lovers, within certain limits." Despite enormous obstacles of class, convention, and erotic desire, Symonds managed slowly to establish with Fusato an intimacy that evolved through several stages and lasted a dozen years, until Symonds' death. Their sexual relationship, as Symonds described it, involved his "passion" and Fusato's "indulgence," his "asking" and Fusato's "concession." Fusato, Symonds reported, was "living with a girl by whom he had two boys." With Symonds' financial support and moral encouragement, ironically, Fusato married, and Marie Fusato later joined her husband in looking after their employer. Two years after meeting Fusato, in 1883, Symonds took the daring step of privately publishing a ten-copy edition of his essay on ancient Greek pederasty, A Problem in Greek Ethics, written ten years earlier.

Henry James wrote to John Addington Symonds from Paris on 22 February 1884, referring to his article on Italy: I sent it you because it was a constructive way of expressing the good will I felt for you in consequence of what you have written about the land of Italy – and of intimating to you, somewhat dumbly, that I am an attentive and sympathetic reader. I nourish for the said Italy an unspeakably tender passion, and your pages always seemed to say to me that you were one of a small number of people who love it as much as I do – in addition to your knowing it immeasurably better. I wanted to recognize this (to your knowledge); for it seemed to me that the victims of a common passion should sometimes exchange a look.

In 1884, John Addington Symonds described A Problem in Greek Ethics to an American scholar and educator, Thomas Sergeant Perry, with whom he was corresponding. Symonds sent Thomas Sergeant Perry a copy of the book, both the 10-copy edition of 1883, and then also one from the 50-copy edition of 1891. Perry read the dangerous essay and later recommended to Symonds a German encyclopedia entry on pederasty about which even the well-informed Symonds had not heard. Perry's own history included a long, easy-going intimacy with James Mills Peirce, an elite, militant defender of "homosexual love."

By the end of his life, Symonds' homosexuality had become an open secret in certain literary and cultural circles. His private memoirs, written (but never completed) over a four-year period from 1889 to 1893, form the earliest known self-conscious homosexual autobiography. On March 3, 1889, Symonds confided to his friend, Horatio Brown, that he had recently begun "a new literary work of the utmost importance, my "Autobiography."" Later in March, an excited Symonds wrote to another confidant, Henry Graham Dakyns, to say that he would let his executors decide what to do with his memoirs, "the most considerable product of my pen." He added: "You see I have "never spoken out."" And it is a "great temptation to speak out" when, for two years, he had been researching the biographies of the artists Benvenuto Cellini and Carlo Gozzi, "men who spoke out so magnificently.""

Between October 1889 and October 1890, Symonds wrote the brief, detailed history of his sexual life that first appeared anonymoysly, in German, in 1896 as part of the first edition of his and Havelock Ellis's pioneering book, Sexual Inversion.

On December 6, 1889, Symonds confided to his 20 years old daughter Madge, who was attending art school in London: "I have just completed the painful book I told you I was writing", his essay on contemporary society's response to sexual relations between men. Symonds' daughter, Madge Vaughan, was probably writer Virginia Woolf's first same-sex crush, though there is no evidence that the feeling was mutual. Woolf was the cousin of her husband William Wyamar Vaughan. Another daughter, Charlotte Symonds, married the classicist Walter Leaf. A third daughter, Dame Katharine Furse, was a British nursing and military administrator, whose longtime partner was Mary Parker Follett. Henry James used some details of Symonds' life, especially the relationship between him and his wife, as the starting-point for the short story "The Author of Beltraffio" (1884).

In 1891, an increasingly emboldened John Addington Symonds printed 50 anonymous copies of A Problem in Modern Ethics, one of the earliest essays in English to defend "sexual inversion."

Over a century after Symonds' death his first work on homosexuality Soldier Love and Related Matter was finally published by Andrew Dakyns (grandson of Symonds' associate, Henry Graham Dakyns), Eastbourne, E. Sussex, England 2007. Soldier Love, or Soldatenliebe since it was limited to a German edition. Symonds' English text is lost. This translation and edition by Dakyns is the only version ever to appear in the author's own language.[21]

My published books: