Queer Places:

Fondamenta Venier Sebastiano, 741, 30123 Venezia VE

Ca’ Torresella on the Zattere, 30100 Venice VE

Angelo

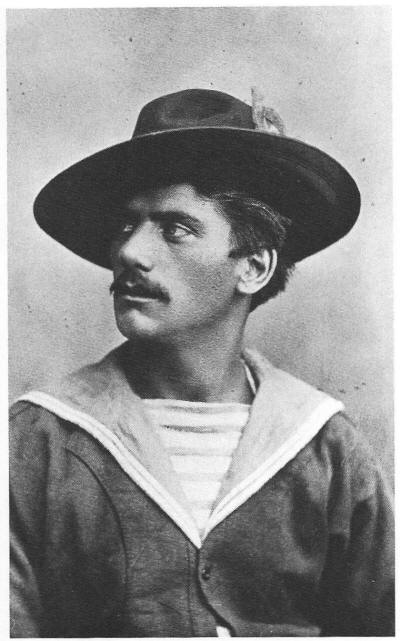

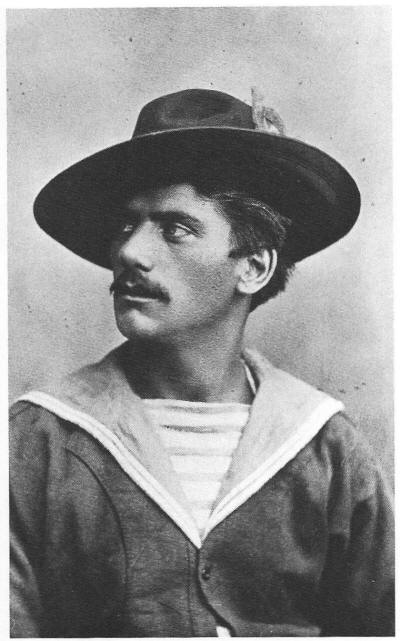

Fusato (1857-1923) was a Venetian gondolier. Angelo Fusato was “an angel with

blue eyes, raven hair and the wild glance of a Triton.” It was love at first

sight when John Addington

Symonds met the Venetian gondolier in 1881. Symonds was renting the piano

nobile of Horatio Brown’s palazzo,

Ca’ Torresella, on the Zattere. Angelo’s looks were all he needed to be

welcomed everywhere as Symond’s traveling companion.

Angelo

Fusato (1857-1923) was a Venetian gondolier. Angelo Fusato was “an angel with

blue eyes, raven hair and the wild glance of a Triton.” It was love at first

sight when John Addington

Symonds met the Venetian gondolier in 1881. Symonds was renting the piano

nobile of Horatio Brown’s palazzo,

Ca’ Torresella, on the Zattere. Angelo’s looks were all he needed to be

welcomed everywhere as Symond’s traveling companion.

Venetian gondoliers, Symonds learned later, were "so accustomed" to the

sexual propositions of travelers "that they think little of gratifying the

caprice of ephemeral lovers, within certain limits." Despite enormous

obstacles of class, convention, and erotic desire, Symonds managed slowly to

establish with Fusato an intimacy that evolved through several stages and

lasted a dozen years, until Symonds' death. Their sexual relationship, as

Symonds described it, involved his "passion" and Fusato's "indulgence," his

"asking" and Fusato's "concession."

Fusato, Symonds reported, was "living with a girl by whom he had two boys."

With Symonds' financial support, he bought Fusato a gondola, and moral

encouragement, Fusato married, and Marie Fusato later joined her husband in

looking after their employer. Two years after meeting Fusato, in 1883, Symonds

took the daring step of privately publishing a ten-copy edition of his essay

on ancient Greek pederasty, A Problem in Greek Ethics, written ten years

earlier.

Whether it was love for money or money for love or both, their relationship

lasted until Symonds’ death twelve years later.

From Symonds' biography:

In the spring of 1881 I was staying for a few days at Venice. I had rooms in the Casa Alberti on the Fondamenta Venier, S. Vio, and it was late in the month of May.

One afternoon I chanced to be sitting with my friend Horatio Brown in a little backyard to the wineshop of Fighetti at S. Elisabetta on the Lido. Gondoliers patronise this place, because Fighetti, a muscular giant, is a hero among them. He has won I do not know how many flags in their regattas. While we were drinking our wine Brown pointed out to me two men in white gondolier uniform, with the enormously broad black hat which was then fashionable. They were servants of a General de Horsey; and one of them was strikingly handsome. The following description of him, written a few days after our first meeting, represents with fidelity the impression he made on my imagination.

He was tall and sinewy, but very slender — for these Venetian gondoliers are rarely massive in their strength. Each part of the man is equally developed by the exercise of rowing; and their bodies are elastically supple, with free sway from the hips and a Mercurial poise upon the ankle. Angelo showed these qualities almost in exaggeration. Moreover, he was rarely in repose, but moved with a singular brusque grace. — Black broad-brimmed hat thrown back upon his matted zazzera of dark hair. — Great fiery grey eyes, gazing intensely, with compulsive effluence of electricity — the wild glance of a Triton. — Short blond moustache; dazzling teeth; skin bronzed, but showing white and delicate through open front and sleeves of lilac shirt. — The dashing sparkle of this splendour, who looked to me as though the sea waves and the sun had made him in some hour of secret and unquiet rapture, was somehow emphasised by a curious dint dividing his square chin — a cleft that harmonised with smile on lips and steady fire in eyes. — By the way, I do not know what effect it would have upon a reader to compare eyes to opals. Yet Angelo's eyes, as I met them, had the flame and vitreous intensity of opals, as though the quintessential colour of Venetian waters were vitalised in them and fed from inner founts of passion. — This marvellous being had a rough hoarse voice which, to develop the simile of a sea-god, might have screamed in storm or whispered raucous messages from crests of tossing waves. He fixed and fascinated me.

Angelo Fusato at that date was hardly twenty-four years of age. He had just served his three years in the Genio, and returned to Venice.

This love at first sight for Angelo Fusato was an affair not merely of desire and instinct but also of imagination. He took hold of me by a hundred subtle threads of feeling, in which the powerful and radiant manhood of the splendid animal was intertwined with sentiment for Venice, a keen delight in the landscape of the lagoons, and something penetrative and pathetic in the man.

How sharp this mixed fascination was at the moment when I first saw Angelo, and how durable it afterwards beame through the moral struggles of our earlier intimacy, will be understood by anyone who reads the sonnets written about him in my published volumes. [Here he lists nearly 60 poems from Vagabunduli Libellus and Animi Figura.] . . . Many of these sonnets were mutilated in order to adapt them to the female sex. . . .

Eight years have elapsed since that first meeting at the Lido. A steady friendship has grown up between the two men brought by accident together under conditions so unpromising. But before I speak of this — the happy product of a fine and manly nature on his side and of fidelity and constant effort on my own — I must revert to those May days in 1881.

The image of the marvellous being I had seen for those few minutes on the Lido burned itself into my brain and kept me waking all the next night. I did not even know his name; but I knew where his master lived. In the morning I rose from my bed unrefreshed, haunted by the vision which seemed to grow in definiteness and to coruscate with phosphorescent fire. A trifle which occurred that day made me feel that my fate could not be resisted, and also allowed me to suspect that the man himself was not unapproachable. Another night of storm and longing followed. I kept wrestling with the anguish of unutterable things, in the deep darkness of the valley of vain desire — soothing my smarting sense of the impossible with idle pictures of what it would be to share the life of this superb being in some lawful and simple fashion.

In these waking dreams I was at one time a woman whom he loved, at another a companion in his trade — always somebody and something utterly different from myself; and as each distracting fancy faded in the void of fact and desert of reality, I writhed in the clutches of chimaera, thirsted before the tempting phantasmagoria of Maya. My good sense rebelled, and told me that I was morally a fool and legally a criminal. But the love of the impossible rises victorious after each fall given it by sober sense. Man must be a demigod of volition, a very Hercules, to crush the life out of that Antaeus, lifting it aloft from the soil of instinct and of appetite which eternally creates it new in his primeval nature.

Next morning I went to seek out Angelo, learned his name, and made an appointment with him for that evening on the Zattere. We were to meet at nine by the Church of the Gesuati. True to time he came, swinging along with military step, head erect and eager, broad chest thrown out, the tall strong form and pliant limbs in action like a creature of the young world's prime. All day I had been wondering how it was that a man of this sort could yield himself so lightly to the solicitation of a stranger. And that is a puzzle which still remains unsolved. I had been told that he was called il matto, or the madcap, by his friends; and I gathered that he was both poor and extravagant. But this did not appear sufficient to explain his recklessness — the stooping to what seemed so vile an act. I am now inclined, however, to imagine that the key to the riddle lay in a few simple facts. He was careless by nature, poor by circumstance, determined to have money, indifferent to how he got it. Besides, I know from what he has since told me that the gondoliers of Venice are so accustomed to these demands that they think little of gratifying the caprice of ephemeral lovers — within certain limits, accurately fixed according to a conventional but rigid code of honour in such matters. There are certain things to which a self-respecting man will not condescend, and any attempt to overstep the line is met by firm resistance.

Well: I took him back to Casa Alberti; and what followed shall be told in the ensuing sonnet, which is strictly accurate — for it was written with the first impression of the meeting strong upon me.

I am not dreaming. He was surely here

And sat beside me on this hard low bed;

For we had wine before us, and I said —

"Take gold: 'twill furnish forth some better cheer".

He was all clothed in white; a gondolier;

White trousers, white straw hat upon his head,

A cream-white shirt loose-buttoned, a silk thread

Slung with a charm about his throat so clear.

Yes, he was here. Our four hands, laughing, made

Brief havoc of his belt, shirt, trousers, shoes:

Till, mother-naked, white as lilies, laid

There on the counterpane, he bade me use

Even as I willed his body. But Love forbade —

Love cried, "Less than Love's best thou shalt refuse!"

Next morning, feeling that I could not stand the strain of this attraction and repulsion — the intolerable desire and the repudiation of mere fleshly satisfaction — I left Venice for Monte Generoso. There, and afterwards at Davos through the summer, I thought and wrote incessantly about Angelo. The series of sonnets entitled "The Sea Calls", and a great many of those indicated above were produced at this time.

In the autumn I returned alone to Venice having resolved to establish this now firmly rooted passion upon some solid basis. I lived in the Casa Barbier. Angelo was still in the service of General de Horsey. But we often met at night in my rooms; and I gradually strove to persuade him that I was no mere light-o-love, but a man on whom he could rely — whose honour, though rooted in dishonour, might be trusted. I gave him a gondola and a good deal of money. He seemed to be greedy, and I was mortified by noticing that he spent his cash in what I thought a foolish way — on dress and trinkets and so forth. He told me something about his history: how he had served three years in the Genio at Venice, Ferrara and Verona. Released from the army, he came home to find his mother dead in the madhouse at S. Clemente, his elder brother Carlo dead of sorrow and a fever after three weeks' illness, his father prostrated with grief and ruined, and his only remaining brother Vittorio doing the work of a baker's boy. The more I got to know the man, the more I liked him.

Yet there were almost insurmountable obstacles to be overcome. These arose mainly from the false position in which we found ourselves from the beginning. He not unnaturally classed me with those other men to whose caprices he had sold his beauty. He could not comprehend that I meant to be his friend, to serve and help him in all reasonable ways according to my power. Seeing me come and go on short flights, he felt convinced that one day or other my will would change and I should abandon him. A just instinct led him to calculate that our friendship, originating in my illicit appetite and his compliance, could not be expected to develop a sound and vigorous growth. The time must come, he reasoned, when this sickly plant would die and be forgotten. And then there was always between us the liaison of shame; for it is not to be supposed that I confined myself to sitting opposite the man and gazing into his fierce eyes of fiery opal. At the back of his mind the predominant thought, I fancy, was to this effect: "Had I not better get what I can out of the strange Englishman, who talks so much about his intentions and his friendship, but whose actual grasp upon my life is so uncertain?" I really do not think that he was wrong. But it made my task very difficult.

I discovered that he was living with a girl by whom he had two boys. They were too poor to marry. I told him that it was his duty to make her an honest woman, not being at that time fully aware how frequent and how binding such connections are in Venice. However, the pecuniary assistance I gave him enabled the couple to set up house; and little by little I had the satisfaction of perceiving that he was not only gaining confidence in me but also beginning to love me as an honest well- wisher.

I need not describe in detail the several stages by which this liaison between myself and Angelo assumed its present form. At last he entered my service as gondolier at fixed wages, with a certain allowance of food and fuel. He took many journeys with me, and visited me at Davos. We grew to understand each other and to conceal nothing. Everything I learned about him made me forget the suspicions which had clouded the beginning of our acquaintance, and closed my eyes to the anomaly of a comradeship which retained so much of passion on my part and of indulgence on his. I found him manly in the truest sense, with the manliness of a soldier and warm soft heart of an exceptionally kindly nature — proud and sensitive, wayward as a child, ungrudging in his service, willing and good-tempered, though somewhat indolent at the same time and subject to explosions of passion. He is truthful and sincere, frank in telling me what he thinks wrong about my conduct, attentive to my wants, perfect in his manners and behaviour — due allowance made for his madcap temperament, hoarse voice and wild impulsive freedom.

I can now look back with satisfaction on this intimacy. Though it began in folly and crime, according to the constitution of society, it has benefited him and proved a source of comfort and instruction to myself. Had it not been for my abnormal desire, I could never have learned to know and appreciate a human being so far removed from me in position, education, national quality and physique. I long thought it hopeless to lift him into something like prosperity — really because it took both of us so long to gain confidence in the stability of our respective intentions and to understand each other's character. At last, by constant regard on my side to his interests, by loyalty and growing affection on his side for me, the end has been attained. His father and brother have profited; for the one now plies his trade in greater comfort, and the other has a situation in the P & O service, which I got for him, and which enables him to marry. And all this good, good for both Angelo and myself, has its taproot in what at first was nothing better than a misdemeanour, punishable by the law and revolting to the majority of human beings.

References:

Support this project

This website is a passion project researched, developed, and funded entirely by me. If you find the content valuable and would like to help support the ongoing research and hosting costs, any contribution is deeply appreciated.

Thank you for keeping this independent resource alive!

My books on Amazon: Elisa Rolle's books

BACK TO HOME PAGE

Angelo

Fusato (1857-1923) was a Venetian gondolier. Angelo Fusato was “an angel with

blue eyes, raven hair and the wild glance of a Triton.” It was love at first

sight when John Addington

Symonds met the Venetian gondolier in 1881. Symonds was renting the piano

nobile of Horatio Brown’s palazzo,

Ca’ Torresella, on the Zattere. Angelo’s looks were all he needed to be

welcomed everywhere as Symond’s traveling companion.

Angelo

Fusato (1857-1923) was a Venetian gondolier. Angelo Fusato was “an angel with

blue eyes, raven hair and the wild glance of a Triton.” It was love at first

sight when John Addington

Symonds met the Venetian gondolier in 1881. Symonds was renting the piano

nobile of Horatio Brown’s palazzo,

Ca’ Torresella, on the Zattere. Angelo’s looks were all he needed to be

welcomed everywhere as Symond’s traveling companion.