Partner Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton

Queer Places:

Riverside St, Watertown, MA 02472, Stati Uniti

Via del Corso, 28, 00187 Roma RM

Via Gregoriana, 38, 00187 Roma RM

Via Margutta, 116, 00187 Roma RM

(1864)

Via Margutta, 5, 00187 Roma RM

Kent House, Rutland Gardens, Knightsbridge, London SW7 1BX, UK

Mount Auburn Cemetery, 580 Mt Auburn St, Cambridge, MA 02138, Stati Uniti

Harriet

Goodhue Hosmer (October 9, 1830 – February 21, 1908) was a

neoclassical sculptor, considered the most

distinguished female sculptor in America during the 19th century. She is

included as one of "the loyal subjects of Her Majesty" in The Court and Camp of

Queen Marian (attributed to Mary Boyle; published by

Emily Faithfull in 1868). William

Wetmore Story, writing to his Boston friend, poet James Russell Lowell, observed

that

Charlotte Cushman,

Harriet Hosmer,

Matilda Hays, and writer

Grace Greenwood formed "a

Harem (Scarem) of emancipated females".

Harriet

Goodhue Hosmer (October 9, 1830 – February 21, 1908) was a

neoclassical sculptor, considered the most

distinguished female sculptor in America during the 19th century. She is

included as one of "the loyal subjects of Her Majesty" in The Court and Camp of

Queen Marian (attributed to Mary Boyle; published by

Emily Faithfull in 1868). William

Wetmore Story, writing to his Boston friend, poet James Russell Lowell, observed

that

Charlotte Cushman,

Harriet Hosmer,

Matilda Hays, and writer

Grace Greenwood formed "a

Harem (Scarem) of emancipated females".

Hosmer is known as the first female professional sculptor.[1] A certain homoeroticism emerged, made all the more remarkable by the fact that many prominent artists of this era—including Thomas Eakins, F. Holland Day, John Singer Sargent, Harriet Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis, and Anne Whitney—had intense romantic attachments with members of their own sex.

Among other technical innovations, Hosmer pioneered a process for turning limestone into marble. Hosmer once lived in an expatriate colony in Rome, befriending many prominent writers and artists. She called the widowed Englishwoman Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton “my sposa” and referred to herself as Ashburton’s “hubbie,” “wedded wife,” and daughter. Writing to Ashburton of a marriage between monarchs, Hosmer added, “They will be as happy in their married life as we are in ours”; in another letter she promised “when you are here I shall be a model wife (or husband whichever you like).” Harriet Hosmer adopted boyish dress and manners and flirted openly with women, but Victorian lifewriting attests that dozens of respectable Englishwomen traveling to Rome were eager to meet her. Her visitors in the late 1860s included a diplomat’s wife, a philanthropic Christian woman, and Anne Thackeray, who traveled to Rome with Lady de Rothschild.

The community of talented women in Rome included artists whose lives and works have become well known in art-historical circles: Harriet Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis, Anne Whitney, and Vinnie Ream; and those whose reputations have remained (until now) buried in the historical record: Emma Stebbins, Margaret Foley, Sarah Fisher Ames, and Louisa Lander. In 1903, Henry James immortalized this community of American women sculptors in Rome by characterizing them as “that strange sisterhood of American lady sculptors who at one time settled upon the seven hills [of Rome] in a white marmorean flock.” Hosmer, Lander, Stebbins, and Foley, under the mentorship of the thespian Charlotte Cushman, formed a close-knit and supportive community (though not without personal and professional jealousies) that the author Nathaniel Hawthorne rendered with some sympathy in his romantic account of American artists in Rome, The Marble Faun (1860).

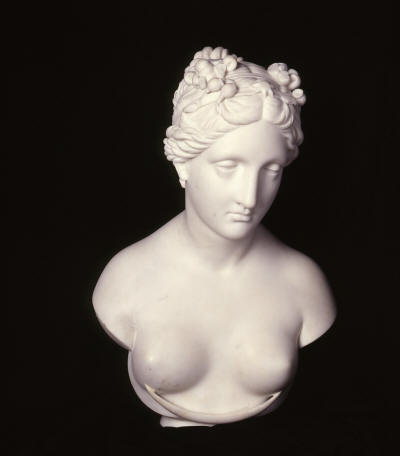

Harriet Hosmer, Hesper, 1852, marble, height 24 in. Watertown Free Public

Library, Mass.

Harriet Hosmer, Daphne, 1854, marble, 26 ½ × 19 ½ × 13 ½ in. Mildred Lane

Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, gift of Wayman Crow

Sr., 1880.

Harriet Hosmer, Medusa, 1854, marble. Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders

Society Purchase, R. H. Tannahill Foundation Fund.

Harriet Hosmer, Oenone, 1854–55, marble, 33 3/8 × 34 ¾ × 26 ¾ in. Mildred Lane

Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, gift of Wayman Crow

Sr., 1855.

Harriet Hosmer, Puck, 1856, marble, 30 ½ × 16 5/8 × 19 ¾ in. Smithsonian

American Art Museum, Washington, D.C., gift of Mrs. George Merrill.

Harriet Hosmer, Zenobia in Chains, 1861, marble. © Courtesy of the Huntington

Art Collections, San Marino, Calif.

Harriet Hosmer, Sleeping Faun, after 1865, marble, 43 ½ × 41 × 16 ½ in. Museum

of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Lucien Carr, 12.709. Photograph © 2014

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Harriet Hosmer, The Waking Faun, 1866–67, now lost. Photograph, Harriet

Goodhue Hosmer Papers, The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard

University, A162-175f-6b.

Harriet Hosmer, Beatrice Cenci, 1856, marble. From the collections of the St.

Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Harriet Hosmer, Freedman’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, 1866, plaster, now

lost. Watertown Free Public Library, Watertown, Mass.

Harriet Hosmer, African Sibyl, design for a portion of the Lincoln Monument,

ca. 1890, now lost. Watertown Free Public Library, Watertown, Mass.

Harriet Hosmer at work on the clay model of Thomas Hart Benton, ca. 1862.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer Collection, The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe

Institute, Harvard University, A162-72-11.

Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge

Harriet Hosmer was born on October 9, 1830 at Watertown, Massachusetts, and completed a course of study at Sedgewick School[2] in Lenox, Massachusetts. Her mother and three siblings died during her childhood.[3] She was a delicate child, and was encouraged by her father, physician Hiram Hosmer, to pursue a course of physical training by which she became expert in rowing, skating, and riding. He also encouraged her artistic passion. She traveled alone in the wilderness of the western United States, and visited the Dakota Indians.[4][5]

Boston’s community of reform-minded professional women created a fertile environment for female accomplishment in the mid–nineteenth century. It was these women whom the young sculptor sought out, gravitating toward such pioneering figures as the writer and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child and later the successful thespian Charlotte Cushman. Encouraging Hosmer’s independence, Child had recognized something special in the young girl. Hatty had “refused to have her feet cramped by the little Chinese shoes, which society places on us all,” Child later wrote in an article on the aspiring young artist. Most likely at Child’s urging, Dr. Hosmer enrolled his daughter at Elizabeth Sedgwick’s Lenox Academy, a progressive boarding school in the Berkshires for audacious girls.

In the 1840s and 1850s, the Berkshire town served as a cultural center for Boston-based writers and intellectuals, including Herman Melville, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Ward Beecher, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was also a magnet for an international coterie of progressive women reformers, among them Frances Ann (Fanny) Kemble, the British actress turned abolitionist; Harriet Martineau, the British writer on women’s rights; Fredrika Bremer, the Finnish feminist; and Anna Jameson, the British feminist and historian—all of whom engaged the young minds at the Lenox Academy. Hosmer came into contact with these powerful women while in Lenox. She developed a lifelong attachment to Catharine Sedgwick, who had traveled to Europe in 1840, publishing Letters from Abroad to Kindred at Home in 1841. At Catharine Sedgwick’s invitation, Kemble first visited Lenox in 1838. There, Sedgwick, Kemble, and the young Hosmer formed a close bond. A few years later, Hosmer would attribute her decision to pursue a sculptural career to her friendship with Kemble.

Hosmer showed an early aptitude for modeling, and studied anatomy with her father. Through the influence of family friend Wayman Crow she attended the anatomical instruction of Dr. Joseph Nash McDowell at the Missouri Medical College (then the medical department of the state university).[6] She lived with Cornelia Crow, an intimate friend she had met at the Lenox Academy, and her family. While in St. Louis, she developed a lasting relationship with Cornelia’s father, Wayman Crow, a leading citizen and philanthropist who would later become one of her primary benefactors.

Hosmer studied in Boston and practiced modeling at home until November 1852, when, with her father and her friend Charlotte Cushman, she went to Rome, where from 1853 to 1860 she was the pupil of the Welsh sculptor John Gibson, and she was finally allowed to study live models. On November 12, 1852, Harriet Hosmer arrived in Rome, accompanied by her father, Dr. Hiram Hosmer; Sarah Jane Clarke Lippincott, the journalist known professionally as Grace Greenwood; Virginia Vaughn, a girlhood friend from Lenox; Charlotte Cushman; Sallie Mercer, Cushman’s African-American maid and “right-hand woman”; and Matilda Hays, Cushman’s partner, a feminist reformer and translator of George Sand’s novels. The socially well-connected Vaughn had introduced Hosmer to Cushman in 1850 after a performance in Boston. Hosmer was immediately taken with this strikingly independent woman and developed a lifelong attachment to her. In a letter to her childhood friend Cornelia Crow Carr, she wrote: “Miss Cushman and Miss Hays (her friend and companion) have left Boston, and I can’t tell you how lonely I feel. I saw a great deal of them during the three weeks that they were in the city.... Isn’t it strange how we meet people in this world and become attached to them in so short a time?” Cushman and Hays represented models of creative freedom for Hosmer, who shared their residence at via del Corso 28 in Rome.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was taken with the household of Matilda Hays and Charlotte Cushman at via del Corso 28: There’s a house of what I call emancipated women, she wrote to a friend. She met Harriet Hosmer in 1853; the two were drawn to one another until the poet’s untimely death in 1861. In her semiautobiographical verse novel, Aurora Leigh, of 1856, Barrett Browning, using her popularity as a poet, gave voice to women’s struggles and championed the talented women who surrounded her in Italy. Her protagonist, Aurora, is based in part upon the fictional character Corinne and the young Hosmer. Barrett Browning touted Hosmer’s liberated lifestyle in Rome, writing that she “emancipates the eccentric life of a perfectly ‘emancipated female.’” She continued, “[Hatty] lives here all alone (at twenty-two); dines and breakfasts at the cafés precisely as a young man would; works from six o’clock in the morning till night, as a great artist must, and this with an absence of pretension and simplicity of manners which accord rather with the childish dimples in her rosy cheeks than with her broad forehead and high aims.”

Fanny Kemble’s sister, Adelaide Sartoris, who had lived in Rome for two years, led a salon on Wednesday and Sunday nights in her apartment atop the Spanish Steps. Trained as an opera singer, she performed regularly at these cosmopolitan gatherings, which Harriet Hosmer attended with regularity. Kemble soon followed her sister to Rome, arriving in January of 1853. Hosmer, enamored with the city and its community of independent women, wrote that the two Kemble sisters were “like two mothers to me.”

Cushman was fiercely protective of her young female charges in Rome and quickly made enemies with the influential American sculptor William Wetmore Story. Writing to his friend the poet James Russell Lowell shortly after the women’s arrival in Rome in 1853, Story described the “furore at 28 Corso,” with its “harem (scarem) as I call it... [of] emancipated females who dwell there in heavenly unity; namely, the Cushman, Grace Greenwood, Hosmer,” and others.

Produced the year after her dear friend Cornelia Crow married Lucien Carr, the Oenone expresses a warm sensuality redolent of Hosmer’s and Crow’s “romantic friendship” in Lenox, an experience that remained central to both their lives. In fact, the sculptor gave a bust of Daphne to Cornelia as a “love gift” in the fall of 1854. “When Daphne arrives, kiss her lips and then remember that I kissed her just before she left me,” Hosmer wrote. However, with its peekaboo sensuality, Oenone transgressed into the carnal world, suggesting a blatant sexuality. The sculpture was never shown publicly in the nineteenth century, remaining instead in the residence of Hosmer’s patron, where it was readily available for Cornelia’s private viewing.

In 1854, Matilda Hays left Cushman for Hosmer, which launched a series of jealous interactions among the three women. Hays eventually returned to live with Cushman, but the tensions between her and Cushman would never be repaired.

While living in Rome, Hosmer associated with a colony of artists and writers that included Nathaniel Hawthorne, Bertel Thorvaldsen, William Makepeace Thackeray, and the two female Georges, George Eliot and George Sand. When in Florence, she was frequently the guest of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning at Casa Guidi.

The artists included

Anne Whitney,

Emma Stebbins,

Edmonia Lewis,

Louisa Lander,

Margaret Foley,

Florence Freeman,

and

Vinnie Ream.[8] Hawthorne was clearly describing these in

his novel ''The Marble Faun'', and Henry James called them a "sisterhood

of American ‘lady sculptors'."[9] As Hosmer is now

considered the most famous female sculptor of her time in America, she is

credited with having 'led the flock' of other female sculptors.[10]

Barbara Leigh Smith met Harriet Hosmer in October 1854, was struck by Hosmer’s unconventionality, describing her as ‘very sturdy, bright and vigorous’, ‘the most tomboyish little woman I ever saw’. Further, she commented: She looks more like a jolly little stone cutter than a lady, and yet she is very fascinating, being so uncommonly clever and lively. She does exactly what is most agreeable to herself and best for her work, and does not care what any one says in the very least.

“Modest and gentle” by reputation, Emma Stebbins was in 1856 the newest member to join Rome’s women’s community. Harriet Hosmer took Stebbins under her wing, escorting her to famous sites and introducing her to members of the artistic community; the two rode their horses together on the Campagna. Hosmer curiously described Stebbins as her “wife” and as a scultrice (woman sculptor), perhaps using these feminine appellations to allude to Stebbins’s passive and dependent nature.

Harriet Hosmer finished her Beatrice Cenci in 1856, in the midst of what could only be called “Cenci-mania” in Rome. Artists and tourists flocked to the ground-level gallery of the Palazzo Barberini to see what was then considered the most beautiful portrait by Guido Reni, his Beatrice Cenci. After arriving in Rome in 1859, Sophia Hawthorne was also thrilled to see the painting in the flesh, located just downstairs from the lovely apartments occupied by William Wetmore Story and his family. Hosmer began her sculpture Beatrice Cenci in the fall of 1854, three years after Guerrazzi had published his novel in Italy. She had been offered a commission for a full-length figure from a colleague of Wayman Crow’s in St. Louis—and she decided upon a statue of Beatrice Cenci. When shown in the United States in 1857, the sculpture elicited a different response from its viewers, one grounded, for the most part, in contemporary antipapist rhetoric. Hosmer, a shrewd businesswoman at the age of twenty-six, exhibited her Beatrice Cenci in London, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. She accompanied the sculpture to the United States, where large crowds viewed the piece. When shown at Cotton’s Gallery in Boston, the figure appealed to a wide audience and generated diverse responses, including a uniquely American political reading.

In 1857, Hosmer received the commission for the Judith Falconnet memorial, a tomb sculpture permanently installed in the church of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte in Rome. In 1857, she opened her own workplace on via Margutta, at the base of the Pincian Hill, just down the street from the Palazzo Patrizi, a lovely old Renaissance palace that housed the studios of the American sculptors Randolph Rogers, Joseph Mozier, Chauncey Ives, and later Margaret Foley. According to Nathaniel Hawthorne, Hosmer occupied a lofty room, with a sky-light window; it was pretty well warmed with a stove; and there was a small orange-tree in a pot, with the oranges growing on it, and two or three flower shrubs in bloom.When Hawthorne visited Hosmer’s studio in 1858, he was clearly troubled by the nature of her femininity. “She had on petticoats, I think; but I did not look so low,” the author offered with feigned modesty. “She had on a male shirt, collar, and cravat,” a manly outfit, which she modified with a feminized “brooch of Etruscan gold; and on her curly head was a picturesque little cap of black velvet; and her face was as bright and funny, and as small of feature, as a child’s.” Hawthorne thought her “very queer, but she seemed to be her actual self, and nothing affected nor made-up; so that... I give her full leave to wear what may suit her best, and to behave as her inner woman prompts.” In the end, his suspicion of the manly woman became clear: “I shook hands with this frank and pleasant little woman—if woman she be, as I honestly suppose, though her upper half is precisely that of a young man.”

In 1857, Hosmer began work on her Zenobia in Chains, creating a small-scale version of the sculpture for which the British historian Anna Jameson provided advice and guidance. Jameson had long fought for women’s rights, especially the right of women artists to enter the Royal Academy School in London. Her support for the young sculptor bolstered Hosmer’s reputation while stimulating the market for her work in Britain. Workmen from John Gibson’s studio prepared the clay and armature for the full-sized model. Upon her return from Tuscany in October 1858, she encountered not only the crisis surrounding Louisa Lander’s career but also malevolent rumors about her own work, “the malignant sarcasm of some of [her] rivals,” Jameson explained, who were suspicious of her professional association with Gibson. Jameson counseled the young artist to ignore the comments heard at the Caffè Greco, the eatery near the Spanish Steps where Anglo-American artists took their meals, engaged in conversation and gossip, and at times learned of commissions. “The originality of a conception remains your own, with the stamp of your mind upon it,” she wrote to Hosmer. “Impertinent and malicious insinuations die away, [but] your work and your fame [will] remain, as I hope, for a long, long future.” Zenobia sailed for Britain in 1862 for display in the International Exposition in London’s Crystal Palace. In May, Cushman, Stebbins, Gibson, and Hosmer traveled to England to view the exhibition. As Hosmer was the only woman to exhibit work at the London Exposition, her career began to surge. “The majestic Zenobia,” the Irish feminist Frances Power Cobbe explained, attracted attention by speaking to the burgeoning women’s rights movement in Britain. She also showed the Medusa bust owned by Lady Marian Alford and the Puck, purchased by the Prince of Wales. The American astronomer Maria Mitchell visited Hosmer’s Roman studio in 1858 and described the technical process by which her fancy piece Puck came into existence.

Bessie Rayner Parkes met Harriet Hosmer in Italy in May 1857, described Hosmer as ‘such a bright little creature; bright hair, bright eyes … as busy as a bee’. Parkes was intrigued by the combination in Hosmer’s dress of singularity and fashionability, and she was delighted by a likeness to her own appearance: She is the funniest little creature not at all rough or slangy but like a little boy…. There is much energy and spirit in a pair of splendid grey eyes, her face is that of an arch faun…. She lives with an old French lady, but conducts herself exactly as she chooses …. She has short curled hair like mine, & usually swept back from a very broad brow, wears a black hat and little feather everywhere, concerts & all, seeming quite ignorant of bonnets; manages her petticoats with a certain extraordinary ease suggestive of trousers – but the finishing and funniest point of all is a very thin waist, & this strangely for a sculptor seems Hatty’s weak point, for all her jackets fit quite tight & neat. Hosmer’s dedication, her ‘sublime steadiness’, impressed her. When Hosmer visited London for the exhibition of Beatrice Cenci, she called on Parkes at the offices of the Waverley Journal and took out a subscription to the magazine. Parkes was introduced by Matilda Mary Hays, who was to leave Rome to become joint editor of The English Woman’s Journal; her essay on Hosmer was printed in July 1858.

Frances Power Cobbe made several excursions to Italy between 1857 and 1862. In Rome Cobbe met not only Harriet Hosmer but a Welsh sculptor, Mary Lloyd, who had studied and worked with Rosa Bonheur. When Cobbe, introduced by Lloyd, visited the French artist, she reported: ‘Nothing I liked about her, so much, however, as her interest in Hattie Hosmer, and her delight in hearing about her Zenobia (triumphans) in the Exhibition.’ Cobbe and Lloyd returned to London in 1862 for what was to become a thirty-year partnership. Hosmer stayed with the couple on her visits to Britain, and joined them in support of women’s enfranchisement: Hosmer, Cobbe and Lloyd were members of the London National Society for Women’s Suffrage in the late 1860s.

Allegations that Hosmer did not do her own work had circulated throughout the Roman community since 1858. Hosmer was furious at the accusations. Having heard these innuendos for too long, she hired a London lawyer to defend her reputation. In January 1864 journals offered their apologies to the artist; retractions were also printed in the London Times and the Galignani Messenger in Rome.

Hosmer had once called Stebbins "wife". But it was with Cushman that Stebbins shared rooms when they moved to Via Gregoriana, 38, in November, 1858. Hosmer became "single", living separately at the same address for several years. But soon Cushman and the headstrong Hosmer were at odds. Hosmer moved accross the Piazza Barberini and next door to artist William Wetmore Story. Eventually their resentments faded, but they never regained their closeness. Charlotte Cushman held her first reception in her new home in January of 1859, beginning a tradition that would continue for many years. Mingling at this festive event were the feminist art historian Anna Jameson, Fanny Kemble, Adelaide Sartoris, and the British author and reformer Mary Howitt, to name just a few. When the Irish feminist Frances Power Cobbe came to town, she noted: There was a brightness, freedom and joyousness among these gifted Americans, which was quite delightful to me. Cushman had the gift of drawing out the best from all who came, explained Emma Crow, the youngest daughter of the philanthropist Wayman Crow.

With the success of the Zenobia in 1858, Harriet Hosmer began plans for a new luxurious studio in Rome at via delle Quattro Fontane 26. She jokingly called it the Palazzetto Barberini (the small Barberini palace) because it was situated just down the street from the grand Palazzo Barberini, where the Story family resided. This was one of the choicest neighborhoods in Rome. “When the studio is done,” she claimed “without exaggeration, there will be no studio in Rome which can hold a candle to it.” In 1865, her new expanded workplace became one of the most famous studios in the city. “Miss Hosmer has one of the most beautiful studios in Rome,” one visitor opined, with “plants and flowers and a fountain setting for her statues and busts.” In her “palace-like studio,” Hosmer presented a new public persona to the art world. No longer the “little impish boy” of earlier years; she now regularly dressed in full Victorian wear—flouncy skirts and lacy cuffs—and sported longer, more carefully coiffed hair, a feminized image in keeping with her mature, professional stature. Her weekly reception days at the new studio were highly celebrated, as she received all her visitors in person. “It was pleasant to find a bright, piquant, woman,” one visitor noted, “instead of the Amazon... which our fancy had conjured from the shadowy realm of gossip.”

Medusa, her first commissioned sculpture, was bought by Mrs. Samuel Appleton, wife of the prosperous Boston merchant and philanthropist, who later owned its pendant, Daphne. In the early 1860s, the Duchess of St. Albans, Lady Sibyl Mary Grey, and Lady Marian Alford, art patron, amateur painter, and intimate of Hosmer, purchased busts of Medusa.

In the 1860s, Henry Wreford promoted a movement of women artists in Rome known as the 12 Star Constellation amongst whom were Charlotte Cushman, Margaret Foley, Harriet Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis, Emma Stebbins. Henry Wreford was a figure of curiosity for historians and literary experts of the time but remained relatively unknown to the wider public despite his substantial role within the political world of pre-unified Italy and his promotion of the culture of gender.

Edmonia Lewis met Harriet Hosmer when the sculptor stopped by her studio in 1865 to see her Bust of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. Suitably impressed with the work, Hosmer encouraged Lewis to visit her in Rome. After selling one hundred plaster copies of the Shaw bust at fifteen dollars apiece, Lewis earned enough money to fund her sojourn to Italy.

Hosmer put her Sleeping Faun into marble in 1865, in response to the popularity of Hawthorne's novel, The Marble Faun. An American critic at the Dublin Exhibition of 1865, where Hosmer first showed the work, described the sculpture as “less coarse... and less inebriate” than the Barberini Faun, a Hellenistic sculpture that presents an image of uninhibited sexuality. The powerful male body reclines in a drunken state, with legs splayed and genitals in full view. Bierstadt alludes to this bawdy sculpture in his Roman Fish Market, in which he poses one of the sleeping Italian men in this indecent pose, clearly referencing the bestial nature of the Italian male. In contrast to the Barberini Faun, Hosmer’s faun, the critic continued, is “not a savage, but a comparatively graceful and refined impersonation of sylvan nature; one of the fauns of Arcady.” The Irish feminist Frances Power Cobbe wrote at length about the sculpture and described it as “an image of ease and joy, and pure, sensuous, delight-brimming existence.”

In 1866 the Englishman Henry Wreford, a freelance correspondent in Italy, described the female artists in Rome collectively as “a fair constellation . . . of twelve stars of greater or lesser magnitude, who shed their soft and humanising influence on a profession which has done so much for the refinement and civilization of man.” Some of Wreford’s twelve stars, incidentally all American sculptors, are still recognizable names even today: Margaret Foley, Florence Freeman, Harriet Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis, and Emma Stebbins. Less known now are the American painter sisters Mary Elizabeth Williams and Abigail Osgood Williams, the Italian sculptor Horatia Augusta Latilla Freeman and her relative, the painter Adah Caroline Latilla, Irish painter and sculptor Jane Morgan, and English sculptor Isabel Cholmelay (her studio was at Palazzetto Sciarra). It is not entirely clear which of these women produced art of “greater magnitude” in Wreford’s mind; his discussion is rather general overall. Indeed, in his article and in others of the period, even the better-known women tend to earn more comments about their personalities, appearances, or behaviors than about their art.

Henry T. Tuckerman, an American writer who lived in Italy, included a brief section on American female sculptors in Rome in his Book of the Artists (1867). In less than five pages, in a volume of more than 600 pages total, he discussed several members of Henry Wreford’s constellation, including Margaret Foley, Florence Freeman,[9] Harriet Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis, and Emma Stebbins. He briefly mentioned Sarah Fisher Clampitt Ames, Louisa Lander, Vinnie Ream, and Anne Whitney, though by that date Lander and Ames had returned to the United States and Ream had not yet arrived in Rome. Tuckerman’s description was hardly complementary; he noted that public appreciation of their art seemed to derive from “national deference to and sympathy with the sex” and from a lack of understanding about art in general. Yet even his dismissive analysis shows awareness of and interest in these women and their activities.

In The Waking Faun, which Hosmer completed in 1867, the young faun awakened to catch the baby satyr at its mischief. The sculpture did not receive the same acclaim as its predecessor. Hosmer had hoped to exhibit both in Paris in 1867 but was unable to resolve The Waking Faun to her satisfaction, explaining that it “fell too far short of the other.”

Within a few years, both Jameson and Barrett Browning were dead. Jameson died in 1860; Barrett Browning in 1861. After the loss of these powerful mentors, Hosmer’s life in Rome took an astounding turn. She entered into a friendship with Maria Sophia, the queen of Naples. In 1868, she began work on a full-length sculptural portrait of the queen. “She came to me the other day dressed exactly as she was” in Gaeta, Hosmer explained. “It will make an interesting statue, for the subject is invested with so much that is historic.” No images of the sculpture exist; whether it was ever translated into marble or just remained in clay is unclear to this day.

In 1873 Hosmer's studio was at Via Margutta, 5.

Hosmer was drawn to the Neoclassical style, which was easy to study given

her presence in Rome. She enjoyed studying mythology, and she created various

representations of mythological icons, such as the sculpture of ''The Sleeping

Faun'', which includes intricate details of elements such as his hair, the

grapes, and the cloth draped over him.

She also designed and constructed

machinery, and devised new processes, especially in connection with sculpture,

such as a method of converting the ordinary limestone of Italy into marble, and

a process of modeling in which the rough shape of a statue is first made in

plaster, on which a coating of wax is laid for working out the finer forms.

Hosmer later lived in Chicago and Terre Haute,

Indiana.

She was devoted for 25 years to Louisa Baring, Lady

Ashburton, widow of Bingham Baring, 2nd Baron

Ashburton (died 1864).[11]

Hosmer died at Watertown, Massachusetts, on February 21, 1908, and is buried in

the family plot at Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge.[12] Aside from the work she produced, Harriet Hosmer made her mark on

art history and feminist and gender studies.{{citation needed|date=June 2016}}

As the National Museum of Women in the Arts put it, "Harriet Goodhue Hosmer

defied 19th-century social convention by becoming a successful sculptor of large

scale, Neoclassical works in marble."[13]

In the

19th century women did not usually have careers, especially careers as

sculptors. Women were not allowed to have the same art education as men, they

were not trained in the making "great" art such as large history paintings,

mythological and biblical scenes, modeling of figure. Women usually produced

artwork that could be done in their home, such as still lives, portraits,

landscapes, and small scale carvings, although even Queen Victoria allowed

her daughter, the Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, to

study sculpture.

Hosmer was not allowed to attend art classes because

working from a live model was forbidden for women, but she took classes in

anatomy to learn the human form and paid for private sculpture lessons. The

biggest career move she made was moving to Rome to study art. Hosmer owned her

own studio and ran her own business. She became a well-known artist in Rome, and

received several commissions.

Hosmer commented on her break from

tradition by saying "I honor every woman who has strength enough to step outside

the beaten path when she feels that her walk lies in another; strength enough to

stand up and be laughed at, if necessary."

Mount Hosmer, near Lansing, Iowa, is named after Hosmer; she

won a footrace to the summit of the hill during a steamboat layover during the

1850s.[14]

During World

War II the Liberty ship Harriet Hosmer was built in Panama City,

Florida, and named in her honor.[15]

A book of

poetry, ''Waking Stone: Inventions on the Life Of Harriet Hosmer'', by Carole

Simmons Oles, was published in 2006.

Her sculpture, ''Puck and Owl'', is featured on the

Boston Women's Heritage Trail.[16]

The Hosmer School in Watertown, Massachusetts is a public elementary school

named in her honor.

My published books: