Wife Sophia Hawthorne

Queer Places:

Bowdoin College, Bath, Maine 04530, Stati Uniti

4 Pond Rd, London SE3 9JL, Regno Unito

24 George St, Marylebone, London W1U, Regno Unito

The Wayside, 455 Lexington Rd, Concord, MA 01742

12 Herbert St, Salem, MA 01970

Tappan House, 297 West St, Lenox, MA 01240

Via di Porta Pinciana, 37, 00187 Roma RM

Casa del Bello, Via dei Serragli, 132, 50125 Firenze FI

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Concord, Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA

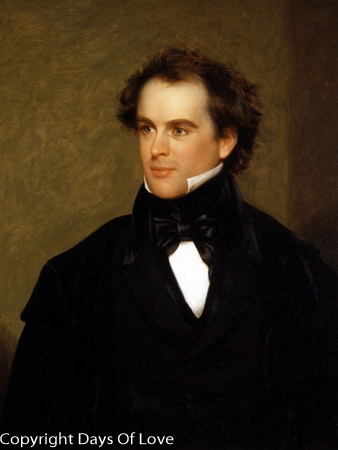

Nathaniel

Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist, dark

romantic, and short story writer.

Herman Melville's Moby Dick explores the intense relationships of men at

sea and is dedicated his masterpiece to his friend and fellow artist Nathaniel

Hawthorne. One of the great literary friendships of the XIX century was that

shared by New England writers Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Melville was devastated as Hawthorne grew distant from him. Most scholars

agree that Melville's Monody is really an elegy to Hawthorne, summing uo his

grief over love rejected. In Moby Dick (1851), which Melville dedicated to

Hawthorne, he describes the interaction between the South Seas islander

Queequeg and the Yankee sailor Ismael, who share a bed one night at New

Bedford's fictious Spouter Inn.

Nathaniel

Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist, dark

romantic, and short story writer.

Herman Melville's Moby Dick explores the intense relationships of men at

sea and is dedicated his masterpiece to his friend and fellow artist Nathaniel

Hawthorne. One of the great literary friendships of the XIX century was that

shared by New England writers Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Melville was devastated as Hawthorne grew distant from him. Most scholars

agree that Melville's Monody is really an elegy to Hawthorne, summing uo his

grief over love rejected. In Moby Dick (1851), which Melville dedicated to

Hawthorne, he describes the interaction between the South Seas islander

Queequeg and the Yankee sailor Ismael, who share a bed one night at New

Bedford's fictious Spouter Inn.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts to Nathaniel Hathorne and the former Elizabeth Clarke Manning. His ancestors include John Hathorne, the only judge involved in the Salem witch trials who never repented of his actions. He entered Bowdoin College in 1821, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in 1824,[1] and graduated in 1825. He published his first work in 1828, the novel Fanshawe; he later tried to suppress it, feeling that it was not equal to the standard of his later work.[2] He published several short stories in periodicals, which he collected in 1837 as Twice-Told Tales. The next year, he became engaged to Sophia Peabody. He worked at the Boston Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a transcendentalist community, before marrying Peabody in 1842. The couple moved to The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, later moving to Salem, the Berkshires, then to The Wayside in Concord. The Scarlet Letter was published in 1850, followed by a succession of other novels. A political appointment as consul took Hawthorne and family to Europe before their return to Concord in 1860. Hawthorne died on May 19, 1864, and was survived by his wife and their three children.

Much of Hawthorne's writing centers on New England, many works featuring moral metaphors with an anti-Puritan inspiration. His fiction works are considered part of the Romantic movement and, more specifically, dark romanticism. His themes often center on the inherent evil and sin of humanity, and his works often have moral messages and deep psychological complexity. His published works include novels, short stories, and a biography of his college friend Franklin Pierce, the 14th President of the United States.

In the 1840s and 1850s, the Berkshire town served as a cultural center for Boston-based writers and intellectuals, including Herman Melville, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry Ward Beecher, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. It was also a magnet for an international coterie of progressive women reformers, among them Frances Ann (Fanny) Kemble, the British actress turned abolitionist; Harriet Martineau, the British writer on women’s rights; Fredrika Bremer, the Finnish feminist; and Anna Jameson, the British feminist and historian—all of whom engaged the young minds at the Elizabeth Sedgwick’s Lenox Academy, a progressive boarding school in the Berkshires for audacious girls.

Hawthorne and his family moved to a small red farmhouse near Lenox, Massachusetts, Tappan House, at the end of March 1850.[55] He became friends with Herman Melville beginning on August 5, 1850 when the authors met at a picnic hosted by a mutual friend.[56] Melville had just read Hawthorne's short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse, and his unsigned review of the collection was printed in The Literary World on August 17 and August 24 entitled "Hawthorne and His Mosses".[57] Melville was composing Moby-Dick at the time, and he wrote that these stories revealed a dark side to Hawthorne, "shrouded in blackness, ten times black".[58] Melville dedicated Moby-Dick (1851) to Hawthorne: "In token of my admiration for his genius, this book is inscribed to Nathaniel Hawthorne."[59]

Harriet Hosmer, Louisa Lander, Emma Stebbins, and Margaret Foley, under the mentorship of the thespian Charlotte Cushman, formed a close-knit and supportive community (though not without personal and professional jealousies) that the author Nathaniel Hawthorne rendered with some sympathy in his romantic account of American artists in Rome, The Marble Faun (1860).

When the Hawthorne family arrived in Rome they were immediately welcomed by the community of Anglo-American artists and writers living in the city, most notably Charlotte Cushman, Emma Stebbins, and Harriet Hosmer. The Hawthornes took up residence at Palazzo Larazani, a lovely road that bordered the parks of the Pincian Hill and the Borghese Gardens, not far from Cushman’s via Gregoriana home. In Rome, Nathaniel Hawthorne traveled in a circle of American artists that included the painters Thomas Buchanon Read and Cephas Giovanni Thompson and the sculptors Randolph Rogers, Joseph Mozier, William Wetmore Story, and Paul Akers; he was also acquainted with the British sculptor John Gibson. Story introduced Hawthorne to Louisa Lander, as they both hailed from the same hometown of Salem, Massachusetts. In the first few months of his residence in the city, Hawthorne conceived the idea for his last novel, The Marble Faun, a romance with American artists as protagonists. Published in 1860, the book brought to the attention of a wide Anglo-American public the careers of talented artists working and living in Rome. In fact, he loosely based his characters upon the lives of Lander, Hosmer, Story, and Akers. Tourists wandered the streets of Rome with The Marble Faun under their arms and visited the studios of American sculptors, hoping to get a glance at the famous Cleopatra by Story or the Dead Pearl Diver by Akers, which were described at length in the novel. Hawthorne also celebrated Hosmer’s Zenobia in Chains, claiming that were he capable of stealing from a lady, he would certainly have made free with Miss Hosmer’s noble statue for use in his novel. Hawthorne was quite taken by Lander, who, at the age of thirty-three, led an exceptional life in Rome. She shared dinners and evenings with the family at the Palazzo Larazani. He recorded seventeen tourist outings with Lander over a five-month period. At times the Hawthorne family—Sophia and the children—joined them; at other times the two scoured the sites of Rome alone. She had genuine talent,... spirit and independence, living in Rome quite alone, in delightful freedom, he reported. She was a young woman, living in almost perfect independence, thousands of miles from her New England home, going fearlessly about these mysterious streets, by night as well as by day, with no household ties, no rule or law but that within her; yet acting with quietness and simplicity, and keeping, after all, within a homely line of right. Hawthorne consented to sit for his portrait, believing that Lander showed great genius in her work. She worked on the bust for several months, declaring the clay model finished on March 31, 1858. By April 7, she was putting the finishing touches on the plaster bust. For Hawthorne, the portrait process had been very intimate. Hawthorne openly supported Lander’s career, urging Ticknor to do what may be in your power to bring Miss Lander’s name favorably before the public.... She is a very nice person, and I like her exceedingly.

Nathaniel Hawthorne left Rome in June, 1858, to spend the summer and early fall in Tuscany. In Florence they joined a lively expatriate community. Initially, they lived in a thirteen-room house, the Casa del Bello in Via dei Serragli, whose backyard was filled with terraces of roses, jasmine, and groves of lemon and orange trees. Later they moved to the countryside, occupying the villa at Montaulto, with its picturesque tower. Figuring prominently in The Marble Faun, the domicile was where the romance took shape in the author’s imagination. Harriet Hosmer, who was staying with the Storys, visited them often. The family spent many an evening at the Casa Guidi with Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

The Hawthornes returned to Rome in mid-October and moved into 68 Piazza Poli, “the snuggest little set of apartments in Rome,” located around the corner from the Trevi Fountain; from these lodgings Hawthorne could “hear the plash in the evening, when other sounds [were] hushed.” In October, when the rumors began circulating of the improper behaviour of Louisa Lander, she had not yet returned from Boston. Harriet Hosmer and Charlotte Cushman were made aware of the accusations and arrived at the Palazzo Poli, the following day ostensibly to discuss the slanderous stories. Ten days later, Una Hawthorne fell ill. After sketching on the Palatine Hill, a lovely area that overlooked the Forum, she contracted “Roman fever” and remained gravely ill with malaria for many months. She suffered from high fevers and delirium; her parents feared for her life. Not until May 1859 did she fully recover, shortly before the family vacated Rome. Lander returned to Rome in November and was eager to see her friends. Together with her sister Elizabeth, she called upon the Hawthornes on the evening of November 9; but to their surprise they were not admitted. The following day, she left her card at the Piazza Poli. Again, no response. The following week, she sent more letters to the Hawthornes; December 5 marked her last attempt to communicate with those whom she had once considered friends. In early December, the author met again with Lander’s supporters—Charlotte Cushman, Harriet Hosmer, Emma Stebbins, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning—to try to resolve the situation. Unfortunately, the meeting came to naught. Hawthorne was true to his pledge and remained forever silent on the issue. Sophia stood steadfastly with her husband.

My published books: