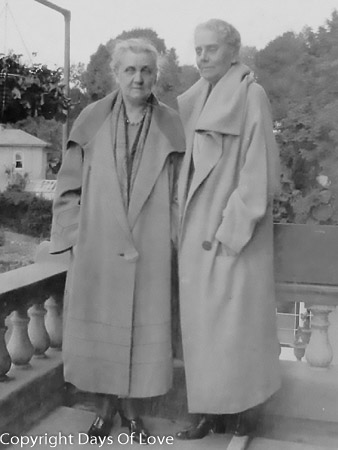

Partner Ellen Gates Starr, Mary Rozet Smith

Queer Places:

John H. Addams Homestead, 425 N Mill St, Freeport, IL 61032, Stati Uniti

Rockford Female Seminary, 5050 E State St, Rockford, IL 61108, Stati Uniti

Hull House, 800 S Halsted St, Chicago, IL 60607, Stati Uniti

Bar Harbor, Maine, Stati Uniti

Cedarville Cemetery, Freeport, Illinois 61032, Stati Uniti

Jane

Addams (September 8, 1860 – May 21, 1935), known as the "mother" of social

work,[1][2]

was a pioneer American settlement activist/reformer, social worker, public

philosopher, sociologist,[3]

public administrator,[4][5]protestor,

author, and leader in women's suffrage and world peace.[6]

Historical figures suspected of having same-sex desires whose personal

documents were destroyed include suffragist

Alice Paul, educator

M. Carey Thomas, interior

designer Henry Davis Sleeper, and

reformers Jane Addams,

Molly Dewson, and

Miriam Van Waters. During

this period, unmarried women often coupled together as long-term companions,

sharing their lives, their homes, their finances, and quite often their beds.

The phenomenon was so common, in fact, that such arrangements were known by

the colloquial term “Boston marriage,” a reference to the 1886 novel The

Bostonians, by Henry James. Some of the most

influential women of this era lived in such relationships. Jane Addams,

founder of the American settlement house movement;

Emily Blackwell, one of the

first female medical doctors in the United States and a pioneer in providing

medical training to other women;

M. Carey Thomas, president of

Bryn Mawr College; Sara

Josephine Baker, an early advocate for childhood public health; and author

Willa Cather are but a few

examples. Surviving documents make it clear that the women involved understood

these relationships to be serious, emotional unions. They refer to their

partners as “My Ever Dear,” “devoted companion,” “lover,” “dearest,” and often

describe lifelong devotion, as when reformer Jane Addams wrote to Mary Rozet

Smith, her partner of more than thirty years, “I miss you dreadfully and am

yours ’til death.”

Jane

Addams (September 8, 1860 – May 21, 1935), known as the "mother" of social

work,[1][2]

was a pioneer American settlement activist/reformer, social worker, public

philosopher, sociologist,[3]

public administrator,[4][5]protestor,

author, and leader in women's suffrage and world peace.[6]

Historical figures suspected of having same-sex desires whose personal

documents were destroyed include suffragist

Alice Paul, educator

M. Carey Thomas, interior

designer Henry Davis Sleeper, and

reformers Jane Addams,

Molly Dewson, and

Miriam Van Waters. During

this period, unmarried women often coupled together as long-term companions,

sharing their lives, their homes, their finances, and quite often their beds.

The phenomenon was so common, in fact, that such arrangements were known by

the colloquial term “Boston marriage,” a reference to the 1886 novel The

Bostonians, by Henry James. Some of the most

influential women of this era lived in such relationships. Jane Addams,

founder of the American settlement house movement;

Emily Blackwell, one of the

first female medical doctors in the United States and a pioneer in providing

medical training to other women;

M. Carey Thomas, president of

Bryn Mawr College; Sara

Josephine Baker, an early advocate for childhood public health; and author

Willa Cather are but a few

examples. Surviving documents make it clear that the women involved understood

these relationships to be serious, emotional unions. They refer to their

partners as “My Ever Dear,” “devoted companion,” “lover,” “dearest,” and often

describe lifelong devotion, as when reformer Jane Addams wrote to Mary Rozet

Smith, her partner of more than thirty years, “I miss you dreadfully and am

yours ’til death.”

Jane Addams had a special friend, Mary Rozet Smith. When they traveled, they wired ahead to be sure to get a double bed. When separated, Addams wrote to Smith, “I miss you dreadfully and am yours till death,” and Smith expressed similar longing, writing, “You can never know what it is to me to have had you and to have you now.” Smith inspired a great deal of enthusiasm among Addams's colleagues. “Will you kiss your dear friend, Miss Smith, for me and tell her that in sleepless nights and even in nice dreams I see her before me as a good angel,” wrote Dutch feminist Aletta Jacobs in 1915. “I have a remembrance of her as one of the sweetest women I ever met in the world,” Jacobs added four years later. And, even more extravagantly, Jacobs concluded in 1923, “I always have admired her and if I would have been a man I should have fallen in love with her.”

.jpg)

International Congress of Women in 1915. left to right:1. Lucy Thoumaian - Armenia, 2. Leopoldine Kulka, 3. Laura Hughes - Canada, 4. Rosika Schwimmer - Hungary, 5. Anika Augspurg - Germany, 6. Jane Addams - USA, 7. Eugenie Hanner, 8. Aletta Jacobs - Netherlands, 9. Chrystal Macmillan - UK, 10. Rosa Genoni - Italy, 11. Anna Kleman - Sweden, 12. Thora Daugaard - Denmark, 13. Louise Keilhau - Norway

Left to right: Catherine E. Marshall, Sir George Paish, Jane Addams, Cor. Ramondt-Hirschmann, Jeanne Melin – Emergency Peace Conference at the Hague "Conference for a New Peace" in 1922

At the turn of the twentieth century, educated women who chose to have

careers often chose to forego heterosexual marriage; many partnered with other

professional women instead. Shown here (left to right) are reformers Julia

Lathrop, Jane Addams, and Mary Eliza McDowell on a 1913 suffrage trip to

Capitol Hill. None of them ever married. Courtesy of the Library of Congress,

LC-USZ62-50050

Hull House

Addams welcomed Emma Goldman’s mentor (and former prince) Peter Kropotkin to Hull House but not Goldman, leading Goldman to comment that “I did not happen to be known to Miss Addams as a princess". Mary Rozet Smith came from a wealthy Chicago family and helped to support both Jane Addams and Hull-House financially for 40 years. She and Addams shared their lives and work, and also a double bed, and were known in the women’s international network and outside it as a couple.

She co-founded, with Ellen Gates Starr, an early settlement house in the United States, Chicago's Hull House that would later become known as one of the most famous settlement houses in America. In an era when presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson identified themselves as reformers and social activists, Addams was one of the most prominent[7] reformers of the Progressive Era. She helped America address and focus on issues that were of concern to mothers, such as the needs of children, local public health, and world peace. In her essay "Utilization of Women in City Government," Jane Addams noted the connection between the workings of government and the household, stating that many departments of government, such as sanitation and the schooling of children, could be traced back to traditional women's roles in the private sphere. Thus, these were matters of which women would have more knowledge than men, so women needed the vote to best voice their opinions.[8] She said that if women were to be responsible for cleaning up their communities and making them better places to live, they needed to be able to vote to do so effectively. Addams became a role model for middle-class women who volunteered to uplift their communities. She is increasingly being recognized as a member of the American pragmatist school of philosophy, and is known by many as the first woman "public philosopher in the history of the United States.[9] In 1889 she co-founded Hull House, and in 1920 she was a co-founder for the ACLU.[10] In 1931 she became the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and is recognized as the founder of the social work profession in the United States.[11]

Generally, Addams was close to a wide set of other women and was very good at eliciting their involvement from different classes in Hull House's programs. Nevertheless, throughout her life Addams did have significant romantic relationships with a few of these women, including Mary Rozet Smith and Ellen Starr. Her relationships offered her the time and energy to pursue her social work while being supported emotionally and romantically. From her exclusively romantic relationships with women, she would most likely be described as a lesbian in contemporary terms, similar to many leading figures in the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom of the time.[56]

Her first romantic partner was Ellen Starr, with whom she founded Hull House, and whom she met when both were students at Rockford Female Seminary. At Rockford Female Seminary Addams also met Julia Lathrop.

In 1889, Addams and Starr visited Toynbee Hall together, and started their settlement house project, purchasing a house in Chicago.[57]

In 1890, Lathrop moved to Chicago where she joined Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr, Alzina Stevens, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Florence Kelley, Mary McDowell, Alice Hamilton, Sophonisba Breckinridge and other social reformers at Hull House.[3] Lathrop ran a discussion group called the Plato Club in the early days of the House. The women at Hull House actively campaigned to persuade Congress to pass legislation to protect children. During the depression years of the early '90s Lathrop served as a volunteer investigator of relief applicants, visiting homes to document the needs of the families.

In the 1930s, Molly Dewson, Jane Addams and others campaigned for Frances Perkins to be Secretary of Labor and urged Eleanor Roosevelt to help secure the position for her.

Addams' second romantic partner was Mary Rozet Smith, who was financially wealthy and supported Addams's work at Hull House, and with whom she shared a house.[58] Lilian Faderman, the notable historian, writes that Jane was in love and she addressed Mary as "My Ever Dear", "Darling" and "Dearest One", and conclusively establishes that they shared the intimacy of a married couple. Their couplehood did not end until 1934, when Mary died of pneumonia, after forty years together.[59] It was said that, "Mary Smith became and always remained the highest and clearest note in the music that was Jane Addams' personal life".[60] Together they owned a summer house in Bar Harbor, Maine. When apart, they would write to each other at least once a day – sometimes twice. Addams would write to Smith, "I miss you dreadfully and am yours 'til death".[61] The letters also show that the women saw themselves as a married couple: "There is reason in the habit of married folks keeping together", Addams wrote to Smith.[62]

My published books: