Partner Eardley Knollys, Desmond Shawe-Taylor

Queer Places:

Long Critchel House, Long Crichel, Wimborne BH21 5LE, UK

105 Cadogan Gardens, Chelsea, London SW3 2RF, Regno Unito

Eton College, Windsor, Windsor and Maidenhead SL4 6DW

University of Oxford, Oxford, Oxfordshire OX1 3PA

Cooleville House, Clogheen Market, Cooleville, Co. Tipperary, Irlanda

Edward Charles Sackville-West, 5th Baron Sackville (13 November 1901 – 4

July 1965) was a British music critic, novelist and, in his last years, a

member of the House of Lords. Musically gifted as a boy, he was attracted as a

young man to a literary life and wrote a series of semi-autobiographical

novels in the 1920s and 1930s. They made little impact, and his more lasting

books are a biography of the poet Thomas de Quincey and The Record Guide,

Britain's first comprehensive guide to classical music on record, first

published in 1951. Michael Bloch describes

Paul Latham in Closet Queens (2015)

as someone who: delighted in causing pain and discomfiture to others; he was

also a promiscuous and predatory homosexual. For more than a decade he

conducted a sado-masochistic affair with

Eddy

Sackville-West (later 5th Baron Sackville) […] a talented writer and

musician, who was finally driven (in 1937) to a nervous breakdown by the

relationship. Rumour had it that Sir

Anthony Eden was a lover of both

Edward

Sackville-West and Edward

Gathorne-Hardy. Sackville-West was reminded of Eden when reading

Mary Renault’s pioneering gay novel

The Charioteer in 1953.

Edward Charles Sackville-West, 5th Baron Sackville (13 November 1901 – 4

July 1965) was a British music critic, novelist and, in his last years, a

member of the House of Lords. Musically gifted as a boy, he was attracted as a

young man to a literary life and wrote a series of semi-autobiographical

novels in the 1920s and 1930s. They made little impact, and his more lasting

books are a biography of the poet Thomas de Quincey and The Record Guide,

Britain's first comprehensive guide to classical music on record, first

published in 1951. Michael Bloch describes

Paul Latham in Closet Queens (2015)

as someone who: delighted in causing pain and discomfiture to others; he was

also a promiscuous and predatory homosexual. For more than a decade he

conducted a sado-masochistic affair with

Eddy

Sackville-West (later 5th Baron Sackville) […] a talented writer and

musician, who was finally driven (in 1937) to a nervous breakdown by the

relationship. Rumour had it that Sir

Anthony Eden was a lover of both

Edward

Sackville-West and Edward

Gathorne-Hardy. Sackville-West was reminded of Eden when reading

Mary Renault’s pioneering gay novel

The Charioteer in 1953.

As a critic and a member of the board of the Royal Opera House, he strove to promote the works of young British composers, including Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett. Britten worked with him on a musical drama for radio and dedicated to him one of his best known works, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings.

Sackville-West was born at Cadogan Gardens, London, the elder child and only son of Major-General Charles John Sackville-West, who later became the fourth Baron Sackville, and his first wife, Maud Cecilia, née Bell (1873–1920). He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford.[1] While at Eton he studied the piano with Irene Scharrer, his housemaster's wife, and became highly proficient, winning the Eton music prize in 1918. His partner Desmond Shawe-Taylor said of him, "not many boys can have played at a school concert the Second Concerto of Rachmaninov. He even contemplated a pianist's career, but was deterred by poor health."[2] At Oxford he made many literary friends, including Maurice Bowra, Roy Harrod and L. P. Hartley, and literature began to rival music as his chief interest.[3] He left Oxford without taking his degree and embarked on a career as a novelist, writing a series of autobiographical novels.[1]

Philip Charles Thomson Ritchie; Edward ('Eddy') Sackville-West

by Lady Ottoline Morrell

vintage snapshot print, 1926

2 7/8 in. x 3 7/8 in. (74 mm x 100 mm) image size

Purchased with help from the Friends of the National Libraries and the Dame Helen Gardner Bequest, 2003

Photographs Collection

NPG Ax142389

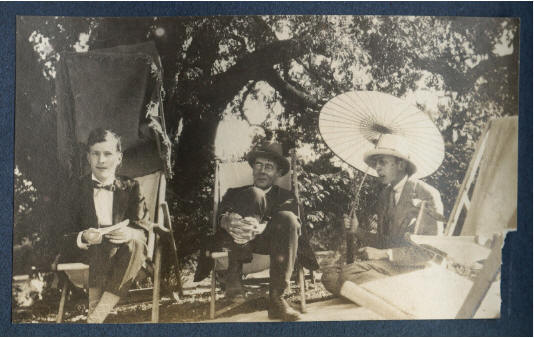

Philip Charles Thomson Ritchie; Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson; Edward ('Eddy') Sackville-West

by Lady Ottoline Morrell

vintage snapshot print, 1922

2 1/8 in. x 3 1/2 in. (55 mm x 90 mm) image size

Purchased with help from the Friends of the National Libraries and the Dame Helen Gardner Bequest, 2003

Photographs Collection

NPG Ax141361

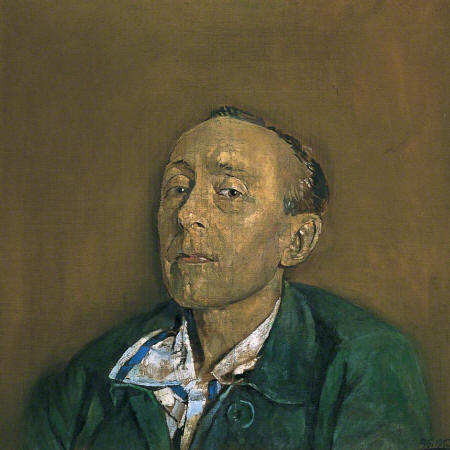

The Honourable Edward Sackville West (1901–1965)

Graham Vivian Sutherland (1903–1980)

Birmingham Museums Trust

In 1924 Edward Sackville-West went to Freiburg to be psychoanalysed with regard to his homosexuality by one Dr Marten. Other homosexual friends were there, enjoying each other while trying to imagine enjoying women. Not surprisingly, Eddy liked Germany. He stayed in Dresden from the autumn of 1927 to the following spring. Christmas was spent with Harold Nicolson in Berlin: ‘The night life of that city,’ Eddy said, ‘is really very strange indeed.’ He gave an account of that strangeness in a letter to E.M. Forster, and later he went back for more: he returned to Berlin for the winter of 1928–29. One evening in 1929, as if he had never been before, Nicolson got a detective to show him around Berlin’s gay bars, but they depressed him. In a letter to his wife (12 April 1929) he commented, ‘I do not like other people’s vices.’

In 1930, after dining with various homosexual men, including E.M. Forster and Lytton Strachey, whose conversation strayed on to the topic of attractive youths, Virginia Woolf said she had received ‘a tinkling, private, giggling impression. As if I had gone into a men’s urinal.’ Of Eddy Sackville-West she said, quite simply, ‘I can’t take Buggerage seriously.’ Hermione Lee, her biographer, comments, as follows: ‘Like Simone de Beauvoir twenty years later … the feminist in her deplored the fact that gay men seemed to want to be women. And she must also have felt that homosexuality was, for the next generation of writers, an exclusive exclusive passport for literary success.’

Sackville-West's family home was Knole in Kent. He maintained rooms there, but it was not until 1945 that he had a home of his own, having lived with friend Kenneth Clark at Upton near Tetbury. Together with Shawe-Taylor he set up home at Long Crichel House near Wimborne. Along with the painter Eardley Knollys and later the literary critic Raymond Mortimer, they established "what in effect was a male salon, entertaining at the weekends a galaxy of friends from the worlds of books and music."[1] In 1956 he also bought Cooleville House at Clogheen in County Tipperary, Ireland. On the death of his father on 8 May 1962 he inherited the title Baron Sackville. He took his seat in the House of Lords but never made a speech.[1]

He died suddenly in 1965 at Cooleville, aged 63.[3] Shawe-Taylor wrote, "Barely a quarter of an hour before, he had been playing to a friend, who was staying with him, the new record of Britten's Songs from the Chinese [performed] by Peter Pears and Julian Bream. When I arrived for the funeral a few days later, the record was still out of its cover—something the meticulous Eddy would never have allowed."[2] He was succeeded in the barony by his cousin Lionel Bertrand Sackville-West.

My published books: