Queer Places:

Novodevichy Cemetery, Luzhnetskiy Proyezd, 2, Moskva, Russia, 119048

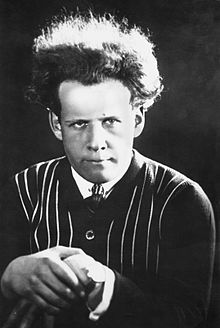

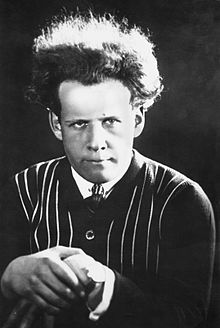

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein[1] (22 January 1898 (10 January) - 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films ''Strike'' (1925), ''Battleship Potemkin'' (1925) and ''October'' (1928), as well as the historical epics ''Alexander Nevsky'' (1938) and ''Ivan the Terrible'' (1944, 1958). In their important decennial poll, the Sight and Sound magazine named his ''Battleship Potemkin'' the 11th greatest movie of all time. [2]

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein[1] (22 January 1898 (10 January) - 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films ''Strike'' (1925), ''Battleship Potemkin'' (1925) and ''October'' (1928), as well as the historical epics ''Alexander Nevsky'' (1938) and ''Ivan the Terrible'' (1944, 1958). In their important decennial poll, the Sight and Sound magazine named his ''Battleship Potemkin'' the 11th greatest movie of all time. [2]

Sergei Eisenstein saw the espousal of Modernism as a way to prevent himself

from eventually sharing Wilde’s fate: he told the Soviet critic Sergei

Tretiakov that, had it not been for the trinity of Marx, Lenin and Freud, he

might have ended up as ‘another Oscar Wilde’.

Eisenstein was born to a middle-class family in Riga, Latvia (then part of the Russian Empire in the Governorate of Livonia), but his family moved frequently in his early years, as Eisenstein continued to do throughout his life. His father, Mikhail Osipovich Eisenstein, was born to a German Jewish father who had converted to Christianity, Osip Eisenstein, and a mother of Swedish descent.[3] [4] His mother, Julia Ivanovna Konetskaya, was from a Russian Orthodox family.[5] According to other sources, both of his paternal grandparents were of Baltic German descent.[6] His father was an architect and his mother was the daughter of a prosperous merchant. Julia left Riga the same year as the Russian Revolution of 1905, taking Sergei with her to St. Petersburg. Her son would return at times to see his father, who joined them around 1910. Divorce followed and Julia left the family to live in France. Eisenstein was raised as an Orthodox Christian, but became an atheist later on.[7] [8]

At the Petrograd Institute of Civil Engineering, Sergei studied architecture and engineering, the profession of his father. In 1918 Sergei left school and joined the Red Army to serve the Bolshevik Revolution, although his father Mikhail supported the opposite side. This brought his father to Germany after the defeat of the Tsarist government, and Sergei to Petrograd, Vologda, and Dvinsk. In 1920, Sergei was transferred to a command position in Minsk, after success providing propaganda for the October Revolution. At this time, he was exposed to Kabuki theatre and studied Japanese, learning some 300 kanji characters, which he cited as an influence on his pictorial development.[9] These studies would lead him to travel to Japan.

In 1920 Eisenstein moved to Moscow, and began his career in theatre working for Proletkult. His productions there were entitled ''Gas Masks,'' ''Listen Moscow,'' and ''Wiseman''. Eisenstein would then work as a designer for Vsevolod Meyerhold. In 1923 Eisenstein began his career as a theorist, by writing ''The Montage of Attractions'' for LEF. Eisenstein's first film, ''Glumov's Diary'' (for the theatre production ''Wiseman''), was also made in that same year with Dziga Vertov hired initially as an "instructor."[10]

''Strike'' (1925) was Eisenstein's first full-length feature film. ''Battleship Potemkin'' (1925) was acclaimed critically worldwide. It was mostly his international critical renown which enabled Eisenstein to direct ''October'' (aka ''Ten Days That Shook The World'') as part of a grand tenth anniversary celebration of the October Revolution of 1917, and then ''The General Line'' (aka ''Old and New''). The critics of the outside world praised them, but at home, Eisenstein's focus in these films on structural issues such as camera angles, crowd movements, and montage brought him and like-minded others, such as Vsevolod Pudovkin and Alexander Dovzhenko, under fire from the Soviet film community, forcing him to issue public articles of self-criticism and commitments to reform his cinematic visions to conform to the increasingly specific doctrines of socialist realism.

In the autumn of 1928, with ''October'' still under fire in many Soviet quarters, Eisenstein left the Soviet Union for a tour of Europe, accompanied by his perennial film collaborator Grigori Aleksandrov and cinematographer Eduard Tisse. Officially, the trip was supposed to allow Eisenstein and company to learn about sound motion pictures and to present the famous Soviet artists in person to the capitalist West. For Eisenstein, however, it was also an opportunity to see landscapes and cultures outside those found within the Soviet Union. He spent the next two years touring and lecturing in Berlin, Zürich, London, and Paris. In 1929, in Switzerland, Eisenstein supervised an educational documentary about abortion directed by Tissé entitled ''Frauennot - Frauenglück''.

Eisenstein co-wrote a pantomime, Columbine’s Garter, partly influenced by

Jean Cocteau and

Francis Poulenc’s Les Mariées de

la Tour Eiffel. He had a photograph of Cocteau, which he had cut out of the

magazine Je Sais Tout, pinned to the wall in his flat. He must have been

thrilled, then, to meet Cocteau when he went to Paris early in 1930; but

embarrassed on the famous occasion a few nights later when he accompanied the

Surrealist poet Paul Éluard to a performance of Cocteau’s La Voix humaine at

the Comédie Française, and Éluard shouted out at the traduced lover, on stage

with her telephone, ‘Who are you talking to? Monsieiur Desbordes?’

Jean Desbordes being Cocteau’s

then lover, this was intended, and taken, as a ribald joke at the expense of

the author. A row broke out, and Éluard had to be ejected from the auditorium

before the play could continue. Cocteau did not associate the offence, if any,

with Eisenstein and when, a short while later, the Russian was threatened with

deportation – he had fallen victim to a flurry of anti-Soviet feeling in

France – both Cocteau and Colette

supported him, even getting him a meeting with Philippe Berthelot, Director of

the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. While still in Paris, Eisenstein frequented

Sylvia Beach’s bookshop bookshop Shakespeare

and Company, where he was pleased to find Paul

Verlaine’s pornographic Hombres being sold, as he put it, ‘under the

counter quite openly’. He attended the salon of

Marie-Laure de Noailles and was invited to visit her husband the vicomte

in his villa at Hyères, but never actually got there. James Joyce gave him a

signed copy of Ulysses, which had just come out; and

Gertrude Stein, whom he met at

Tristan Tzara’s home, gave him advice on

his imminent trip to the United States.

In late April 1930, Jesse L. Lasky, on behalf of Paramount Pictures, offered Eisenstein the opportunity to make a film in the United States. He accepted a short-term contract for $100,000 and arrived in Hollywood in May 1930, along with Aleksandrov and Tisse.

Eisenstein proposed a biography of munitions tycoon Sir Basil Zaharoff and a film version of ''Arms and the Man'' by George Bernard Shaw, and more fully developed plans for a film of ''Sutter's Gold'' by Jack London, but on all accounts failed to impress the studio's producers. Paramount then proposed a movie version of

Theodore Dreiser's ''An American Tragedy''. This excited Eisenstein, who had read and liked the work, and had met Dreiser at one time in Moscow. Eisenstein completed a script by the start of October 1930, but Paramount disliked it completely and, additionally, found themselves intimidated by Major Frank Pease, president of the Hollywood Technical Director's Institute. Pease, an anti-communist, mounted a public campaign against Eisenstein. On October 23, 1930, by "mutual consent", Paramount and Eisenstein declared their contract null and void, and the Eisenstein party were treated to return tickets to Moscow at Paramount's expense.

Eisenstein was thus faced with returning home a failure. The Soviet film industry was solving the sound-film issue without him and his films, techniques, and theories were becoming increasingly attacked as 'ideological failures' and prime examples of formalism. Many of his theoretical articles from this period, such as ''Eisenstein on Disney'', have surfaced decades later as seminal scholarly texts used as curriculum in film schools around the world.

Eisenstein and his entourage spent considerable time with Charlie Chaplin, who recommended that Eisenstein meet with a sympathetic benefactor in the person of American socialist author

Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's works had been accepted by and were widely read in the USSR, and were known to Eisenstein. The two had mutual admiration and between the end of October 1930 and Thanksgiving of that year, Sinclair had secured an extension of Eisenstein's absences from the USSR, and permission for him to travel to Mexico. The trip to Mexico was for Eisenstein to make a film produced by Sinclair and his wife, Mary Craig Kimbrough Sinclair, and three other investors organized as the "Mexican Film Trust".

On November 24, 1930, Eisenstein signed a contract with the Trust "upon the basis of his desire to be free to direct the making of a picture according to his own ideas of what a Mexican picture should be, and in full faith in Eisenstein's artistic integrity." The contract also stipulated that the film would be "non-political", that immediately available funding came from Mary Sinclair in an amount of "not less than Twenty-Five Thousand Dollars", that the shooting schedule amounted to "a period of from three to four months", and most importantly that: "Eisenstein furthermore agrees that all pictures made or directed by him in Mexico, all negative film and positive prints, and all story and ideas embodied in said Mexican picture, will be the property of Mrs. Sinclair..." A codicil to the contract allowed that the "Soviet Government may have the [finished] film free for showing inside the U.S.S.R." Reportedly, it was verbally clarified that the expectation was for a finished film of about an hour's duration.

By 4 December, Eisenstein was en route to Mexico by train, accompanied by Aleksandrov and Tisse. Later he produced a brief synopsis of the six-part film which would come, in one form or another, to be the final plan Eisenstein would settle on for his project. The title for the project, ''¡Que viva México!'', was decided on some time later still. While in Mexico Eisenstein mixed socially with

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Eisenstein admired these artists and Mexican culture in general, and they inspired Eisenstein to call his films "moving frescoes". The Left U.S. film community eagerly followed Eisenstein's progress within Mexico as is chronicled within Chris Robe's book ''Left of Hollywood: Cinema, Modernism, and the Emergence of U.S. Radical Film Culture''.[11]

After a prolonged absence, Stalin sent a telegram expressing the concern that Eisenstein had become a deserter. Under pressure, Eisenstein blamed Mary Sinclair's younger brother, Hunter Kimbrough, who had been sent along to act as a line producer, for the film's problems. Eisenstein hoped to pressure the Sinclairs to insinuate themselves between him and Stalin, so Eisenstein could finish the film in his own way. The furious Sinclairs shut down production and ordered Kimbrough to return to the United States with the remaining film footage and the three Soviets to see what they could do with the film already shot, estimates ranging from 170,000 lineal feet with ''Soldadera'' unfilmed, to an excess of 250,000 lineal feet.

For the unfinished filming of the "novel" of ''Soldadera'', without incurring any cost, Eisenstein had secured 500 soldiers, 10,000 guns, and 50 cannons from the Mexican Army, but this was lost due to Sinclair's cancelling of production. When Eisenstein arrived at the American border, a customs search of his trunk revealed sketches and drawings of Jesus caricatures amongst other lewd pornographic material. His re-entry visa had expired, and Sinclair's contacts in Washington were unable to secure him an additional extension. Eisenstein, Aleksandrov, and Tisse were allowed, after a month's stay at the U.S.-Mexico border outside Laredo, Texas, a 30-day "pass" to get from Texas to New York, and thence depart for Moscow, while Kimbrough returned to Los Angeles with the remaining film.

On 19 April 1932, Eisenstein set sail from New York on the Europa. The

world of, if not the desire for, the Mexican peasant was left far in their

wake as, for the duration of the crossing, he shared a table with those two

cosmopolitan queens, Noël Coward and

the critic and actor Alexander

Woollcott.

Eisenstein toured the American South, on his way to New York. In mid-1932, the Sinclairs were able to secure the services of Sol Lesser, who had just opened his distribution office in New York, Principal Distributing Corporation. Lesser agreed to supervise post-production work on the miles of negative—at the Sinclairs' expense—and distribute any resulting product. Two short feature films and a short subject—''Thunder Over Mexico'' based on the "Maguey" footage, ''Eisenstein in Mexico'', and ''Death Day'' respectively—were completed and released in the United States between the autumn of 1933 and early 1934. Eisenstein never saw any of the Sinclair-Lesser films, nor a later effort by his first biographer, Marie Seton, called ''Time in the Sun'', released in 1940. He would publicly maintain that he had lost all interest in the project. In 1978, Gregori Aleksandrov released - with the same name in contravention to the copyright - his own version, which was awarded with the Honorable Golden Prize at the 11th Moscow International Film Festival in 1979. Later, in 1998, Oleg Kovalov edited a free version of the film, calling it "Mexican Fantasy".

Peter Greenaway's 2015 film ''Eisenstein in Guanajuato'' is about the director's gay love affair with his guide during his stay in Mexico.

Eisenstein's foray into the West made the staunchly Stalinist film industry look upon him with a suspicion that would never completely disappear. He apparently spent some time in a mental hospital in Kislovodsk in July 1933, ostensibly a result of depression born of his final acceptance that he would never be allowed to edit the Mexican footage. He was subsequently assigned a teaching position at the State Institute of Cinematography where he had taught earlier and in 1933 and 1934 was in charge of writing curriculum.

Some trunks that Eisenstein had sent to Hollywood from Mexico were opened

by US Customs and found to contain many of his homosexually explicit drawings

and a sheaf of photographs of male nudes. On 27 October 1934, he married Pera

Attasheva, an actress and journalist. This was clearly a marriage of

convenience: the couple lived separately and, far from their relationship’s

ever being consummated, Eisenstein himself said that they never so much as

kissed. He did not even mention his wife in his memoirs.

When

Paul Robeson spent a fortnight in Moscow at

the end of 1934, he saw Eisenstein virtually every day, giving rise to a

shiver of suggestive gossip. Similarly, there would be unfounded rumours about

the relationship between Eisenstein and Nikolai Cherkassov, the star of his

films Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible (1942–44, 1946). Of the

films Eisenstein never made, among the more intriguing was a proposal for a

piece about Lawrence of Arabia, whose

complex psychology the director felt he might capture, like that of Ivan, in

pure images.

Then, in 1935, Eisenstein was assigned another project, ''Bezhin Meadow'', but it appears the film was afflicted with many of the same problems as ''¡Que viva México!''. Eisenstein unilaterally decided to film two versions of the scenario, one for adult viewers and one for children; failed to define a clear shooting schedule; and shot film prodigiously, resulting in cost overruns and missed deadlines. Boris Shumyatsky, the ''de facto'' head of the Soviet film industry, finally called a halt to the filming and cancelled further production. The thing which appeared to save Eisenstein's career at this point was that Stalin ended up taking the position that the ''Bezhin Meadow'' catastrophe, along with several other problems facing the industry at that point, had less to do with Eisenstein's approach to filmmaking as with the executives who were supposed to have been supervising him. Ultimately this came down on the shoulders of Shumyatsky, who in early 1938 was denounced, arrested, tried and convicted as a traitor, and shot. (The production executive at Film studio Mosfilm, where ''Meadow'' was being made, was also replaced, but without further executions.)

Eisenstein was thence able to ingratiate himself with Stalin for 'one more chance', and he chose, from two offerings, the assignment of a biopic of ''Alexander Nevsky,'' with music composed by Sergei Prokofiev.[12] This time, he was assigned a co-scenarist, Pyotr Pavlenko, to bring in a completed script; professional actors to play the roles; and an assistant director, Dmitri Vasilyev, to expedite shooting.

The result was a film critically well received by both the Soviets and in the West, which won him the Order of Lenin and the Stalin Prize. It was an obvious allegory and stern warning against the massing forces of Nazi Germany, well played and well made. The script had Nevsky utter a number of traditional Russian proverbs, verbally rooting his fight against the Germanic invaders in Russian traditions.[13] This was started, completed, and placed in distribution all within the year 1938, and represented not only Eisenstein's first film in nearly a decade but also his first sound film.

Within months of its release, Stalin entered into a pact with Hitler, and ''Nevsky'' was promptly pulled from distribution. Eisenstein returned to teaching and was assigned to direct Richard Wagner's ''Die Walküre'' at the Bolshoi Theatre. After the outbreak of war with Germany in 1941, ''Nevsky'' was re-released with a wide distribution and earned international success. With the war approaching Moscow, Eisenstein was one of many filmmakers evacuated to Alma-Ata, where he first considered the idea of making a film about Czar Ivan IV. Eisenstein corresponded with Prokofiev from Alma-Ata, and was joined by him there in 1942. Prokofiev composed the score for Eisenstein's film and Eisenstein reciprocated by designing sets for an operatic rendition of ''War and Peace'' that Prokofiev was developing.

Eisenstein's film, ''Ivan The Terrible, Part I'', presenting Ivan IV of Russia as a national hero, won Joseph Stalin's approval (and a Stalin Prize), but the sequel, ''Ivan The Terrible, Part II'', was criticized by various authorities and would go unreleased until 1958. All footage from the still incomplete ''Ivan The Terrible, Part III'' was confiscated, and most of it was destroyed (though several filmed scenes still exist today).

In 1934 in the Soviet Union, Eisenstein married filmmaker and screenwriter Pera Atasheva (born Pearl Moiseyevna Fogelman; born in 1900, died on 24 September 1965) [14] [15] and remained married until his death in 1948, though there has long been some speculation about his sexual orientation. [16] They had no children.

Eisenstein's health was also failing. He was struck by a serious heart attack on February 2, 1946, and spent much of the following year recovering. He died of another heart attack at the age of 50. He was found on the floor of his Moscow flat on the morning of February 11, 1948. The body lay in state in the Hall of the Cinema Workers, beneath a gold-embroidered velvet pall and surrounded by a profusion of flowers, before being cremated on February 13. The ashes were buried in the snow-covered ground of the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.[17]

My published books:

BACK TO HOME PAGE

- ^ Sergei Eisenstein, From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Woods, Gregory. Homintern . Yale University Press. Edizione del

Kindle.

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein[1] (22 January 1898 (10 January) - 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films ''Strike'' (1925), ''Battleship Potemkin'' (1925) and ''October'' (1928), as well as the historical epics ''Alexander Nevsky'' (1938) and ''Ivan the Terrible'' (1944, 1958). In their important decennial poll, the Sight and Sound magazine named his ''Battleship Potemkin'' the 11th greatest movie of all time. [2]

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein[1] (22 January 1898 (10 January) - 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director and film theorist, a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is noted in particular for his silent films ''Strike'' (1925), ''Battleship Potemkin'' (1925) and ''October'' (1928), as well as the historical epics ''Alexander Nevsky'' (1938) and ''Ivan the Terrible'' (1944, 1958). In their important decennial poll, the Sight and Sound magazine named his ''Battleship Potemkin'' the 11th greatest movie of all time. [2]