Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

28 Cambridge Turnpike, Concord, MA 01742

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, 34 Bedford St, Concord, MA 01742

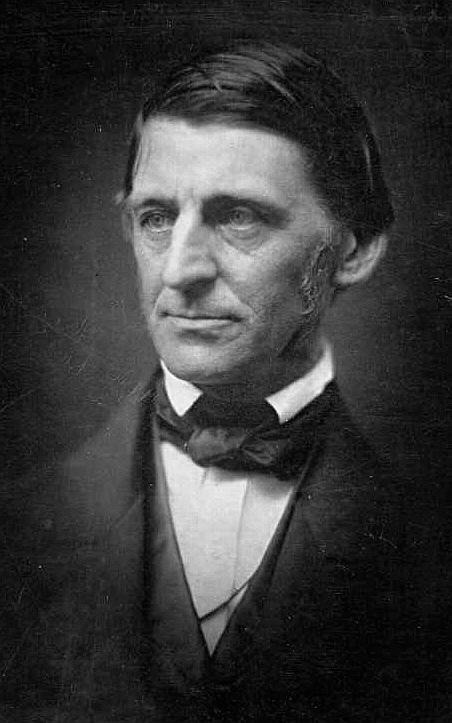

Ralph

Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882)[5]

was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, and poet who led the

transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a

champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing

pressures of society, and he disseminated his thoughts through dozens of

published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures across the United

States. Such

major figures as Emily Dickinson,

Ralph Waldo Emerson, and

Margaret Fuller glorified

same-sex friendship, while Walt

Whitman filled his poetry with robust imagery celebrating male

"ashesiveness". Louisa May

Alcott extolled the virtues of intimate same-sex friendship in her 1870

novel An Old-Fashioned Girl, in which she describes the lives of two women

artists.

Ralph

Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803 – April 27, 1882)[5]

was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, and poet who led the

transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a

champion of individualism and a prescient critic of the countervailing

pressures of society, and he disseminated his thoughts through dozens of

published essays and more than 1,500 public lectures across the United

States. Such

major figures as Emily Dickinson,

Ralph Waldo Emerson, and

Margaret Fuller glorified

same-sex friendship, while Walt

Whitman filled his poetry with robust imagery celebrating male

"ashesiveness". Louisa May

Alcott extolled the virtues of intimate same-sex friendship in her 1870

novel An Old-Fashioned Girl, in which she describes the lives of two women

artists.

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote an essay titled “On Friendship.” Emerson was one of the most influentail American thinkers of the XIX century; as an essayist, poet and lecturer, he philosophized about the relationship between man and God, and was a leader of the trascendental movement. As a student at Harvard, Emerson' attention was drawn to a young scholar, Martin Gay. Though he later excised portions of the text, Emerson's 1821 journal is full of statements of affections for Gay, as well as a "memory sketch" portrait. Gay "haunted" Emerson's thoughts for over two years. In 1822 Emerson wrote, "It is with difficulty that I can now recall those sensations of vivid pleasure which his presence was wont to waker spontaneously."

Emerson gradually moved away from the religious and social beliefs of his contemporaries, formulating and expressing the philosophy of transcendentalism in his 1836 essay "Nature". Following this work, he gave a speech entitled "The American Scholar" in 1837, which Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. considered to be America's "intellectual Declaration of Independence."[6]

Emerson wrote most of his important essays as lectures first and then revised them for print. His first two collections of essays, Essays: First Series (1841) and Essays: Second Series (1844), represent the core of his thinking. They include the well-known essays "Self-Reliance",[7] "The Over-Soul", "Circles", "The Poet", and "Experience." Together with "Nature",[8] these essays made the decade from the mid-1830s to the mid-1840s Emerson's most fertile period. Emerson wrote on a number of subjects, never espousing fixed philosophical tenets, but developing certain ideas such as individuality, freedom, the ability for mankind to realize almost anything, and the relationship between the soul and the surrounding world. Emerson's "nature" was more philosophical than naturalistic: "Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul." Emerson is one of several figures who "took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world."[9]

He remains among the linchpins of the American romantic movement,[10] and his work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers and poets that followed him. "In all my lectures," he wrote, "I have taught one doctrine, namely, the infinitude of the private man."[11] Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of Henry David Thoreau, a fellow transcendentalist.[12]

Emerson's religious views were often considered radical at the time. He believed that all things are connected to God and, therefore, all things are divine.[162] Critics believed that Emerson was removing the central God figure; as Henry Ware Jr. said, Emerson was in danger of taking away "the Father of the Universe" and leaving "but a company of children in an orphan asylum".[163] Emerson was partly influenced by German philosophy and Biblical criticism.[164] His views, the basis of Transcendentalism, suggested that God does not have to reveal the truth but that the truth could be intuitively experienced directly from nature.[165] When asked his religious belief, Emerson stated, "I am more of a Quaker than anything else. I believe in the 'still, small voice,' and that voice is Christ within us."[166]

Emerson may have had erotic thoughts about at least one man.[178] During his early years at Harvard, he found himself attracted to a young freshman named Martin Gay about whom he wrote sexually charged poetry.[67][179] He also had a number of romantic interests in various women throughout his life,[67] such as Anna Barker[180] and Caroline Sturgis.[181]

During his early life, Emerson seems to develop a hierarchy of races based on faculty to reason or rather, whether African slaves were distinguishably equal to white men based on their ability to reason.[171] In a journal entry written in 1822, Emerson wrote about a personal observation: "It can hardly be true that the difference lies in the attribute of reason. I saw ten, twenty, a hundred large lipped, lowbrowed black men in the streets who, except in the mere matter of language, did not exceed the sagacity of the elephant. Now is it true that these were created superior to this wise animal, and designed to control it? And in comparison with the highest orders of men, the Africans will stand so low as to make the difference which subsists between themselves & the sagacious beasts inconsiderable."[173]

As with many supporters of slavery, during his early years, Emerson seems to have thought that the faculties of African slaves were not equal to their white owners. But this belief in racial inferiorities did not make Emerson a supporter of slavery.[171] Emerson wrote later that year that "No ingenious sophistry can ever reconcile the unperverted mind to the pardon of Slavery; nothing but tremendous familiarity, and the bias of private interest".[173] Emerson saw the removal of people from their homeland, the treatment of slaves, and the self-seeking benefactors of slaves as gross injustices.[172] For Emerson, slavery was a moral issue, while superiority of the races was an issue he tried to analyze from a scientific perspective based what he believe to be inherited traits.[174]

Emerson saw himself as a man of "Saxon descent". In a speech given in 1835 titled "Permanent Traits of the English National Genius", he said, "The inhabitants of the United States, especially of the Northern portion, are descended from the people of England and have inherited the traits of their national character".[175] He saw direct ties between race based on national identity and the inherent nature of the human being. White Americans who were native-born in the United States and of English ancestry were categorized by him as a separate "race", which he thought had a position of being superior to other nations. His idea of race was based more on a shared culture, environment, and history than on scientific traits that modern science defines as race. He believed that native-born Americans of English descent were superior to European immigrants, including the Irish, French, and Germans, and also as being superior to English people from England, whom he considered a close second and the only really comparable group.[171]

Emerson did not become an ardent abolitionist until 1844, though his journals show he was concerned with slavery beginning in his youth, even dreaming about helping to free slaves. In June 1856, shortly after Charles Sumner, a United States Senator, was beaten for his staunch abolitionist views, Emerson lamented that he himself was not as committed to the cause. He wrote, "There are men who as soon as they are born take a bee-line to the axe of the inquisitor. ... Wonderful the way in which we are saved by this unfailing supply of the moral element".[167] After Sumner's attack, Emerson began to speak out about slavery. "I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom", he said at a meeting at Concord that summer.[168] Emerson used slavery as an example of a human injustice, especially in his role as a minister. In early 1838, provoked by the murder of an abolitionist publisher from Alton, Illinois named Elijah Parish Lovejoy, Emerson gave his first public antislavery address. As he said, "It is but the other day that the brave Lovejoy gave his breast to the bullets of a mob, for the rights of free speech and opinion, and died when it was better not to live".[167] John Quincy Adams said the mob-murder of Lovejoy "sent a shock as of any earthquake throughout this continent".[169] However, Emerson maintained that reform would be achieved through moral agreement rather than by militant action. By August 1, 1844, at a lecture in Concord, he stated more clearly his support for the abolitionist movement: "We are indebted mainly to this movement, and to the continuers of it, for the popular discussion of every point of practical ethics".[170]

Walt Whitman's 1856 Leaves of Grass included one of XIX century's America's major sex manifestos, a passionate prose plea for the open treatment of sexuality in the nation's literature. This appeared in an open letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson who, in a rhapsodic private letter to Whitman, had praised the writer's first edition, then found his private communication reprinted, without permission, in Whitman's second edition.

On a sharp late-winter’s day early in 1860 on Boston Common, America’s Plato, Ralph Waldo Emerson, perhaps Harvard’s most illustrious graduate still, walked the Beacon Street path the better part of several hours with the poet most would agree is America’s greatest. Back and forth, up and down, Whitman confronted Emerson’s misgivings and foreboding about the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass with deep feeling that day: the end of it all, what Whitman called “a bully dinner”1—and the publication of perhaps the most famous homosexual poetry ever written.

When asked by a reporter upon docking in New York who were the greatest American literary figures, Oscar Wilde at once answered Walt Whitman, but in the same breath insisted also on Ralph Waldo Emerson—“New England’s Plato,” Wilde called him, whose “Attic genius” he thought so highly of that when he was in prison and allowed to choose only a few books, one was Emerson’s essays. He quoted from Emerson twice in De Profundis—and very significant quotes they were: “Nothing is more rare in any man than an act of his own”; “all martyrdoms seemed mean to the lookers on.”

Emerson is often known as one of the most liberal democratic thinkers of his time who believed that through the democratic process, slavery should be abolished. While being an avid abolitionist who was known for his criticism of the legality of slavery, Emerson struggled with the implications of race.[171] His usual liberal leanings did not clearly translate when it came to believing that all races had equal capability or function, which was a common conception for the period in which he lived.[171] Many critics believe that it was his views on race that inhibited him from becoming an abolitionist earlier in his life and also inhibited him from being more active in the antislavery movement.[172] Much of his early life, he was silent on the topic of race and slavery. Not until he was well into his 30s did Emerson begin to publish writings on race and slavery, and not until he was in his late 40s and 50s did he became known as an antislavery activist.[171]

Later in his life, Emerson's ideas on race changed when he became more involved in the abolitionist movement while at the same time he began to more thoroughly analyze the philosophical implications of race and racial hierarchies. His beliefs shifted focus to the potential outcomes of racial conflicts. Emerson's racial views were closely related to his views on nationalism and national superiority, specifically that of the Saxons of ancient England, which was a common view in the United States of that time. Emerson used contemporary theories of race and natural science to support a theory of race development.[174] He believed that the current political battle and the current enslavement of other races was an inevitable racial struggle, one that would result in the inevitable union of the United States. Such conflicts were necessary for the dialectic of change that would eventually allow the progress of the nation.[174] In much of his later work, Emerson seems to allow the notion that different races will eventually mix in America. This hybridization process would lead to a superior race that would be to the advantage of the superiority of the United States.[176]

Emerson was a supporter of the spread of community libraries in the 19th century, having this to say of them: "Consider what you have in the smallest chosen library. A company of the wisest and wittiest men that could be picked out of all civil countries, in a thousand years, have set in best order the results of their learning and wisdom."[177]

My published books: