Queer Places:

60 W 17th St, New York, NY 10011

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

17 Red Lion Square, London

Le Palais Royal, 8 Rue de Montpensier, 75001 Paris

The

Albany, Albany Court Yard, Mayfair, London W1J 0LR

Beach House, 82A Brighton Rd, Worthing BN11 2EN, UK

21 Ashley Place, London

Edward Knoblock (born Edward Gustav Knoblauch; April 7, 1874 – July 19, 1945) was an

homosexual American-born British playwright and novelist most remembered for the often revived 1911 play, Kismet. When

Violet Trefusis and

Vita Sackville-West went off to

Paris, they stayed in the flat of Edward Knoblock.

Edward Knoblock (born Edward Gustav Knoblauch; April 7, 1874 – July 19, 1945) was an

homosexual American-born British playwright and novelist most remembered for the often revived 1911 play, Kismet. When

Violet Trefusis and

Vita Sackville-West went off to

Paris, they stayed in the flat of Edward Knoblock.

Knoblock was born at 60, West 17th Street, New York City in April 1874, of German parents and was the grandson of the Berlin architect Eduard Knoblauch. Following the sudden death of his father, an investment banker, his family spent over two years in Berlin, where he regularly visited the theatre. In his teens he was determined to become a playwright, despite his father's dying wish that he should take up architecture. Gaining a place at Harvard, he studied Moliere's comedies in addition to Homer, Euripides and Shakespeare. He was a devoted member of Harvard's Delta Kappa Epsilon Fraternity. Founded in 1851, this exclusive society boasts six American Presidents among its alumni - including both Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt - as well as J. P. Morgan and Cole Porter. Neil Armstrong even planted its flag on the Moon. Today it remains highly influential, offering the largest scholarship endowment of any Delta Kappa Epsilon Fraternity. Knoblock also joined Harvard's Signet Society, whose alumni include Leonard Bernstein and T. S. Eliot. On graduating with a B.A. degree in 1896 Knoblock was elected "Ivy Orator of the Class of '96", which entailed delivering a humorous speech. He then embarked on a remarkable literary career.

After working in Paris for a few years, he settled in London at 17 Red Lion Square, evolving a close relationship with the Kingsway Theatre. One of his earliest plays, Kismet (1911), was to prove his most successful. Set in Baghdad, Kismet was a Middle Eastern fantasy that told the story of a poet, his daughter, a prince, and a wicked wazir. It ran at the Garrick Theatre from April 1911 to January 1912, and in 1953 was turned into a popular Broadway musical. Milestones (1912), which Knoblock wrote in collaboration with English playwright Arnold Bennett, was an unsympathetic portrayal of the English aristocracy in the midst of social change. It reached over 600 performances at the Royalty Theatre. Knoblock's other Broadway hit was Marie-Odile (1915), a drama about the Franco-Prussian War.

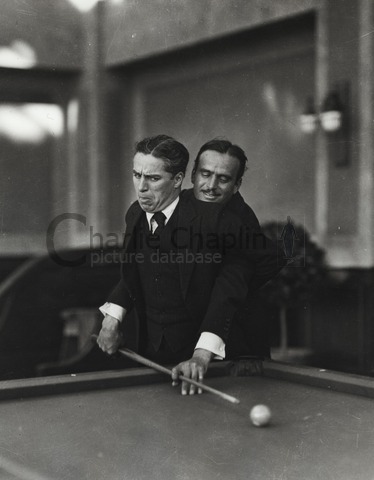

Edward Knoblock and Douglas Fairbanks

Edward Knoblock

John Lavery (1856–1941)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Studio Still Life

William Nicholson (1872–1949)

Tate, Bequeathed by Edward Knoblock 1945

Panels by William Nicholson

In 1912 Knoblock commissioned his friend William Nicholson a complete set of panels for his Paris apartment at Palais Royal. At the painting were executed on glass their preservation has been something miraculous. Among Knoblock's friends were three leading protagonist of the Regency Revival: Mrs Dolly Mann, the influential decorator and Lord Gerald Wellesley and A.E. Richardson, architects and arbiters of taste among the advanced neo-Georgians. In 1912 the Palais Royal was looked upon by French people as decayed and antiquated. Knoblock was among the first to resuscitate it, till then inhabited only by little employees, clerks and poor shopkeepers. When Knoblock left the apartment he brought the panels painted by Nicholson with him.

In August 1914, Knoblock was determined to join the Army but his doctor prevented him as he was still recovering from an operation. A superb linguist, he offered his services to the War Office as a translator but his application was mislaid. Assigned a clerical role at the Indian Secret Intelligence Service, he approached his friend Compton Mackenzie, a prominent literary figure who had been appointed Director of Military Intelligence in the Aegean, in the hope of better work. Mackenzie wangled Knoblock a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve; Knoblock excitedly bought his naval uniform and sword. It was then realised that as he was still an American citizen, Knoblock was ineligible and would have to join the Royal Naval Air Service instead. He duly added the "woollen eagles" to his tunic. Just before sailing for Greece he heard of his commission in the General Service Branch (Army) of the Intelligence Department, which would not be gazetted until after he had left. Just to be sure, he took with him both his army and R.N.A.S. uniforms and swords.

He became a British subject in 1916 during World War I, anglicized the spelling of his name, received a commission as a captain in the British Army and served in the Secret Service Bureau in the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and Greece.

The success of his plays enabled Knoblock to get a bachelor's apartment at Albany, a set of rooms decorated with a flamboyant richness of effects including marble walls and Lyons silk curtains in purple with a palmette border to set off the solemn Regency furniture. There he entertained numerous society guests such as Gerald du Maurier and the painter John Lavery. He also became a member of Pratt's and the Beefsteak Club.

In 1917 he, along with Lord Gerald Wellesley and Albert Richardson, attended the dismal wartime sale of the Thomas Hope furniture from The Deepdene, Surrey, the greatest event in the early phase of the Regency Revival. Between them the three secured many of the most important pieces and, largely because of his conspicuous success that day, Knoblock acquired his Regency House. Spending the rest of his leave in Brighton with the actor Robert Lorraine, he found a neglected house near Arundel and bought it on the spot. With its magnificent sea views and parkland, Beach House was to be his obsession for the next seven years. The house was a substantial and handsome villa with rooms of the correct period and noble proportions to house Hope's monumental furniture. Knoblock was a lifelong collector of Regency style furniture and furnishings and kept much of the celebrated Thomas Hope collection intact. With the help of the Scottish architect Ormrod Maxwell Ayrton, Knoblock set about the restoration of Beach House and by 1921, when the house was photographed for Country Life, it had become the most fully realised and eloquent statement of the scholarly aspect of the neo-Regency ideal. But Knoblock re-affirmed the confident modernity of his taste in 1912 by making William Nicholson panels the principle decorative element. Following Edward Knoblock's death, the glass panels were again moved and came into the possession of Lord Mersey who installed them briefly on the stairs of his Sussex house, Bignor Park. Subsequently, by the terms of Lord Mersey's generous gift they came to the National Trust. The Trust made them over on long loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Knoblock was the subject of one of the most repeated stories involving the gaffe-prone actor John Gielgud, which, pressed by Emlyn Williams, Gielgud confessed was true. While Knoblock and Gielgud were dining one day at The Ivy a man passed their table, and Gielgud said, "Thank God he didn't stop, he's a bigger bore than Eddie Knoblock – oh, not you, Eddie!" Williams asked how Knoblock reacted, and Gielgud replied, "He just looked slightly puzzled, and went on boring."[2]

Knoblock wrote many screenplays, perhaps the best known being Douglas Fairbanks' Robin Hood (1922), though he was uncredited,[3] and The Three Musketeers (1921). Plays written by Knoblock alone include The Shulamite (1906),[4] The Faun (1911), Kismet (1911), My Lady's Dress (1914), Marie-Odile (1915), Tiger! Tiger! (1918), and Grand Hotel (1931). Among his novels are The Ant Heap (1929), The Man With Two Mirrors (1931), The Love Lady (1933), and Inexperience (1941).[5][6] Knoblock often worked with a collaborator. His plays Milestones (1912), and London Life (1924) were co-written with Arnold Bennett. His play Speakeasy, written with George Rosener, became a 1929 film of the same name. Similarly, The Good Companions, originally published in 1929 by J.B. Priestley, was dramatized jointly by Knoblock and the author in 1931 under the same title.[7][8][9]

Edward Knoblock died in July 1945 at 21 Ashley Place, the London home of his sister, Gertrude Knoblauch, a well-known sculptor.[9] A consummate socialite and bon vivant, his autobiography, Round the Room, was published in 1939.

My published books: