Partner Flora Murray

Queer Places:

(1907) 14B Hyde Park Mansions, Marylebone Road,

London

(1910) 114a Harley Street, London

(1934)

Pauls End (now Gatemoor Grange), Pauls Hill, Penn, High Wycombe HP10 8NZ, UK

Women's Hospital for Children, 688 Harrow Rd, London W10, UK

Holy Trinity Churchyard

Penn, Chiltern District, Buckinghamshire, England

Louisa

Garrett Anderson CBE (28

July 1873 – 15 November 1943) was a medical pioneer, a member of the Women's

Social and Political Union, a suffragette,

and social reformer.

She was the daughter of the founding medical pioneer Elizabeth Garrett

Anderson, whose biography she wrote in 1939. Anderson was the

Chief Surgeon of the Women's Hospital Corps (WHC) and a Fellow of the Royal

Society of Medicine. Her aunt, Dame

Millicent Fawcett, was a British suffragist.

Her partner was fellow doctor and suffragette Flora Murray.

In May 1915, Drs Louisa Garrett

Anderson and Flora Murray

founded the Endell Street military hospital in London and from 1916 onwards,

women doctors began to work in hospitals on the front line in Malta, Salonika,

Egypt, India, East Africa and Palestine. Her name and picture (and those of 58 other women

and men's suffrage supporters)

are on the

plinth of the

statue of

Millicent Fawcett in

Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.

Louisa

Garrett Anderson CBE (28

July 1873 – 15 November 1943) was a medical pioneer, a member of the Women's

Social and Political Union, a suffragette,

and social reformer.

She was the daughter of the founding medical pioneer Elizabeth Garrett

Anderson, whose biography she wrote in 1939. Anderson was the

Chief Surgeon of the Women's Hospital Corps (WHC) and a Fellow of the Royal

Society of Medicine. Her aunt, Dame

Millicent Fawcett, was a British suffragist.

Her partner was fellow doctor and suffragette Flora Murray.

In May 1915, Drs Louisa Garrett

Anderson and Flora Murray

founded the Endell Street military hospital in London and from 1916 onwards,

women doctors began to work in hospitals on the front line in Malta, Salonika,

Egypt, India, East Africa and Palestine. Her name and picture (and those of 58 other women

and men's suffrage supporters)

are on the

plinth of the

statue of

Millicent Fawcett in

Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.

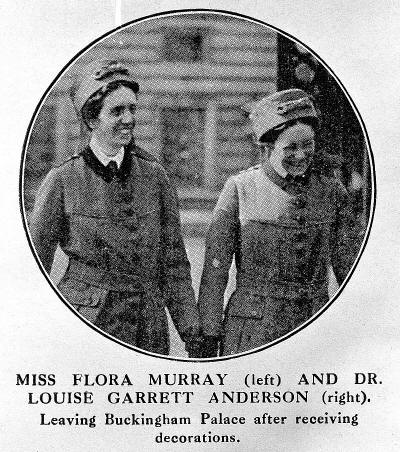

Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson, a formidably competent couple, established the first of the hospitals set up and staffed by women in Europe and Russia during the First World War in a Parisian hotel in September 1914. Murray’s partner, Louisa Garrett Anderson, was the daughter of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, a woman whose story is central to the mid-Victorian women’s movement and whose famously determined struggle to become a doctor placed her as the first woman on the Medical Register in 1865. Murray and Anderson found each other through the suffrage campaign. Their intimate companionship, ‘effectively a marriage’ marked by identical diamond rings, lasted until Murray’s death in 1923; the gravestone in the churchyard near where they lived in Buckinghamshire bears the epitaph ‘We were gloriously happy’.

Unlike the mass of women who had female partners during the period 1890-1960, there is information about a fascinating group of pioneering women doctors in Britain: there are biographies and auto-biographies, appearances in contemporary reminiscences and surveys of successful women, obituaries and entries in the Dictionary of National Biography and Who's Who. These particular women — Louisa Martindale, Louisa Aldrich Blake, Flora Murray, Octavia Wilberforce and their partners — formed a relatively cohesive group united by their common profession of medicine and by geographical location, social class, and strong ties of friendship and respect. However, while there is a relative profusion of material charting their lives, its emphasis is on their professional, rather than their personal, lives. It is these women's careers as doctors, the hospitals in which they worked, the practices they built up, the research articles that they wrote, in essence the contribution that they made to medicine, that is the focus of interest.

Louisa Garrett Anderson (1873–1943)

Francis Dodd (1874–1949)

Royal Free Hospital

Flora Murray (front row, second on right) and Louisa Garrett Anderson

(front row, first on right), with colleagues outside the Hôtel Claridge, 1914

.jpg/800px-Elizabeth_and_Louisa_Garrett_Anderson,_Alfred_Caldecott_and_another,_c.1910._(22531360049).jpg)

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Louisa Garrett Anderson, Alfred Caldecott and another in 1910 on the day they went to see the Prime Minister

Louisa Garrett Anderson was the oldest of three children of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first woman to qualify as a doctor in Britain, co-founder of the London School of Medicine for Women and Britain's first elected woman Mayor. Her father was James George Skelton Anderson, co-owner of the Orient Steamship Company with his uncle Arthur Anderson.[1] She was educated at St Leonards School in St Andrews and London School of Medicine for Women, where she received her Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery in 1898. Anderson received her Doctor of Medicine in 1900, enrolled in further postgraduate studies at Johns Hopkins Medical School and traveled to observe operations in Paris and Chicago.[2]

Despite her education, Anderson was unable to join a general major hospital, as attitudes at the time opposed female doctors treating both men and women. As a result, in 1902, she joined the New Hospital for Women, a women's-only hospital founded by her mother which treated women and children. She first worked as a surgical assistant and later as a senior surgeon. Anderson performed gynecological and general operations, and co-published a paper with the hospital pathologist in 1908 discussing her hysterectomy operations and dissecting the 265 cases of uterine cancer treated at the New Hospital for Women.[2]

From 1903, Louisa had been active in organizations affiliated with the NUWSS, which advocated for gaining voting rights through peaceful means. Frustrated by the lack of progress on voting rights, in 1907 Louisa became an active member of the more radical WSPU.[3] On 18 November 1910, Anderson joined her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, Alfred Caldecott, Hertha Ayrton, Mrs Elmy, Hilda Brackenbury, Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, and 300 women to petition Prime Minister Asquith for voting rights.[4] The protest became known as Black Friday, due to the violence and sexual assault the protesters faced from the police and male bystanders.[5] More than one hundred women were arrested, including Louisa, but all were released without charge.[5] In 1912, Anderson was imprisoned in Holloway, briefly, for her suffragette activities which included breaking a window by throwing a brick. In 1914, Anderson joined the new group of men and women in United Suffragists which had branches in London, Liverpool and Edinburgh.[4]

When the First World War broke out, Anderson and Flora Murray founded the Women's Hospital Corps (WHC), and recruited women to staff it.[6] Believing that the British War Office would reject their offer of help, and knowing that the French were in need of medical assistance, they offered their assistance to the French Red Cross.[7] The French accepted their offer and provided them the space of a newly built hotel in Paris as their hospital.[8] Murray was appointed Médecin-en-Chef (chief physician) and Anderson became the chief surgeon.[7] Murray reported in her diary that visiting representatives of the British War Office were astonished to find a hospital run successfully by British women, and the hospital was soon treated as a British auxiliary hospital rather than a French one.[7] In addition to the hospital in Paris, the Women's Hospital Corps also ran another military hospital in Wimereux.[8] In January 1915, casualties began to be evacuated to England for treatment. The War Office invited Murray and Anderson to return to London to run a large hospital, the Endell Street Military Hospital (ESMH), under the Royal Army Medical Corps. ESMH treated almost 50,000 soldiers between May 1915 and September 1919 when it closed.[8] At Endell, Anderson and the hospital pathologist, Helen Chambers, pioneered a new method of treating septic wounds, an antiseptic ointment called BIPP (bismuth, iodoform, and paraffin paste). The paste had been invented by James Rutherford Morison. After positive results from some initial tests by Anderson, Morison asked Anderson and Chambers to run a larger trial of BIPP in 1916. Anderson published case studies in The Lancet, concluding that this method saved patients pain and was better than the Carrel-Dakin method, which used a more powerful antiseptic but had to be frequently reapplied to be effective. Since bandages could be left on for longer, the BIPP method reduced time spent changing bandages by as much as 80%.[9] BIPP was widely adopted by surgeons for the rest of the war, although opinion among doctors remained divided as to the best method for wound treatment. Despite continued debate, BIPP was also used in the Second World War and continues to be in use today in ear, nose, throat, maxillofacial, and neurosurgery procedures.[10]

Anderson is buried at Holy Trinity Church with Murray, near to their home in Penn, Buckinghamshire. The inscription on the gravestone reads "Louisa Garrett Anderson, C.B.E., M.D., Chief Surgeon Women's Hospital Corps 1914–1919. Daughter of James George Skelton Anderson and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson of Aldeburgh, Suffolk. Born 28th July 1873, died November 15. 1943. We have been gloriously happy."[11]

The archives of Louisa Garrett Anderson are held at The Women's Library at the Library of the London School of Economics, ref. 7LGA].[12][13]

My published books: