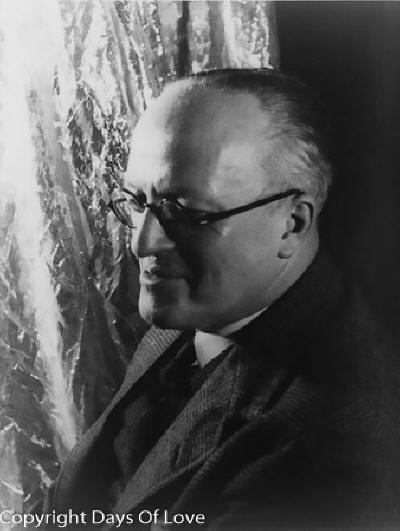

Partner Harold Cheevers

Queer Places:

The King's School, 25 The Precincts, Canterbury CT1 2ES

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Brackenburn, Keswick CA12 5UG, Regno Unito

St John, Keswick CA12, Regno Unito

Sir

Hugh Seymour Walpole, CBE (13 March 1884 – 1 June 1941) was an English

novelist. He was the son of an Anglican clergyman, intended for a career in

the church but drawn instead to writing. Among those who encouraged him were

the authors Henry James

and Arnold Bennett. His skill at scene-setting and vivid plots, as well as his

high profile as a lecturer, brought him a large readership in the United

Kingdom and North America. He was a best-selling author in the 1920s and 1930s

but has been largely neglected since his death. Hugh Walpole dedicated the

novel The Young Enchanted to

Lauritz Melchior, and also paid his singing lessons with

Victor Beigel. Walpole was

friends with Lord Ronald Storrs

and James Agate.

W. Somerset Maugham told

Walpole a downright lie about Cakes and Ale: "I certainly never intended Alroy

Kear to be a portrait of you." When Maugham was viciously attacked in America,

in Gin and Bitters, Walpole rushed to his defence. He was warm-hearted and

impulsively kind. Osbert Sitwell

wrote: "I don't think there was any younger writer of any worth who has not at

one time or another received kindness of an active kind, and at a crucial

moment, from Hugh."

Sir

Hugh Seymour Walpole, CBE (13 March 1884 – 1 June 1941) was an English

novelist. He was the son of an Anglican clergyman, intended for a career in

the church but drawn instead to writing. Among those who encouraged him were

the authors Henry James

and Arnold Bennett. His skill at scene-setting and vivid plots, as well as his

high profile as a lecturer, brought him a large readership in the United

Kingdom and North America. He was a best-selling author in the 1920s and 1930s

but has been largely neglected since his death. Hugh Walpole dedicated the

novel The Young Enchanted to

Lauritz Melchior, and also paid his singing lessons with

Victor Beigel. Walpole was

friends with Lord Ronald Storrs

and James Agate.

W. Somerset Maugham told

Walpole a downright lie about Cakes and Ale: "I certainly never intended Alroy

Kear to be a portrait of you." When Maugham was viciously attacked in America,

in Gin and Bitters, Walpole rushed to his defence. He was warm-hearted and

impulsively kind. Osbert Sitwell

wrote: "I don't think there was any younger writer of any worth who has not at

one time or another received kindness of an active kind, and at a crucial

moment, from Hugh."

By 1909, Henry James was in a reciprocated semi-public infatuation with Hugh Walpole, a man 40 years his junior. The reactions of his friends, including gay men, ranged from disapproval to bemused acceptance. At Cambridge, always looking for "the ideal friend", Walpole fell idealistically in love with old A.C. Benson. At this time Hugh was expecting rather hopelessly to become a clergyman; Benson saw, as no one else did, that he would make a writer, and introduced him to Henry James, the chief intellectual experience of Hugh's life. The Master was touched by Hugh's youthful zest for experience and desire for intimacy. Henry James had never been able to let his hair down, and deplored his "own starved past", wished that "he had reached out more, claimed more" - a characterstically cautious way of putting it.

After his first novel, The Wooden Horse, in 1909, Walpole wrote prolifically, producing at least one book every year. He was a spontaneous story-teller, writing quickly to get all his ideas on paper, seldom revising. His first novel to achieve major success was his third, Mr Perrin and Mr Traill, a tragicomic story of a fatal clash between two schoolmasters. During the First World War he served in the Red Cross on the Russian-Austrian front, and worked in British propaganda in Petrograd and London. In the 1920s and 1930s Walpole was much in demand not only as a novelist but also as a lecturer on literature, making four exceptionally well-paid tours of North America.

As a gay man at a time when homosexual practices were illegal for men in Britain, Walpole conducted a succession of intense but discreet relationships with other men, and was for much of his life in search of what he saw as "the perfect friend". He eventually found one, a married policeman, with whom he settled in the English Lake District. Having as a young man eagerly sought the support of established authors, he was in his later years a generous sponsor of many younger writers. He was a patron of the visual arts and bequeathed a substantial legacy of paintings to the Tate Gallery and other British institutions.

In London he met W. A. T. Ferris, a young Indian Army officer of about his own age, and began a friendship which was to last, although years often passed without their seeing each other, for the rest of his life. The Wooden Horse, in 1909, is dedicated to him.

Walpole's output was large and varied. Between 1909 and 1941 he wrote thirty-six novels, five volumes of short stories, two original plays and three volumes of memoirs. His range included disturbing studies of the macabre, children's stories and historical fiction, most notably his Herries Chronicle series, set in the Lake District. He worked in Hollywood writing scenarios for two Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films in the 1930s, and played a cameo in the 1935 version of David Copperfield.

In the 1910s Percy Anderson was closely associated with the young novelist Hugh Walpole. Walpole wrote: "He has all the knowledge and reminiscence of his age, and doesn't seem in the very least bit old. Anyhow he wants somebody and I want somebody, so that's all right." They set up home together in a fisherman's cottage at Polperro, in those idyllic pre-1914 days. He held on to this entrancing spot, until it was ruined by the march of progress after the war, when he looked for "somewhere more open, and with less village gossip and intrigue".

In September 1920, when Lauritz Melchior was singing the Steersman's Song, from Wagner's The Flying Dutchman at a Prom Concert, he met the popular novelist and passionate Wagnerite Hugh Walpole and the two quickly became firm friends, travelling together and staying in each other's houses. On a visit to Walpole's cottage in Polperro Melchior "caused a sensation by singing at a concert in the village", and later on a visit to Helston he and Walpole both took part in the Floral Dance. In December 1921 on a visit with Walpole to his (Walpole's) parents in Edinburgh, Melchior gave a concert in the Usher Hall. Walpole provided the fledgling Helden tenor with financial aid in February 1922, paying in advance two-thirds of the fees for his studies under Victor Beigel. In 1923, Walpole gave Melchior a further £800, enabling him to continue his studies with Ernst Grenzebach and the legendary dramatic soprano of the Vienna Court Opera, Anna Bahr von Mildenburg.[1]

When Melchior decided to marry, Walpole was crushed and wrote in his diary on July 16, 1924: "In the morning D. (Walpole called Melchior David, hence the abbreviation D.) came to see me, and in the garden at the bottom of this house there was the most desperate struggle of our friendship. It ended in his victory and my resolve to pull myself round and adopt the young woman."

In November 1924, the novelist Hugh Walpole went to Berlin to hear his friend the Danish tenor Lauritz Melchior singing at the Opera, and found the city ‘dirty and exceedingly wicked’.

At the end of 1924 Walpole met Harold Cheevers, who soon became his friend and companion and remained so for the rest of Walpole's life. In Hart-Davis's words, he came nearer than any other human being to Walpole's long-sought conception of a perfect friend.[76] Cheevers, a policeman, with a wife and two children, left the police force and entered Walpole's service as his chauffeur. Walpole trusted him completely, and gave him extensive control over his affairs. Whether Walpole was at Brackenburn or Piccadilly, Cheevers was almost always with him, and often accompanied him on overseas trips. Walpole provided a house in Hampstead for Cheevers and his family.[77]

The headmaster of King's School, Canterbury, Fred Shirley, was another of Hugh Walpole's innumerable friends, with whom he stayed and was "blissfully happy", on his last visit to Cornwall.

After the outbreak of the Second World War Walpole remained in England, dividing his time between London and Keswick, and continuing to write with his usual rapidity. He completed a fifth novel in the Herries series and began work on a sixth.[n 17] His health was undermined by diabetes. He overexerted himself at the opening of Keswick's fund-raising "War Weapons Week" in May 1941, making a speech after taking part in a lengthy march, and died of a heart attack at Brackenburn, aged 57.[95] Walpole went back to Brackenburn to die. Harold was away in Cornwall, looking after his old parents who had suffered in the savage blitz on Plymouth. He got back in time for a last talk with Hugh - "it may be out last chance" - in which he went over their life together, all the places they had seen, all the fun they had had, the life he had so much enjoyed, the happiest thing in it his friendship with Harold. Next morning, Harold took his outstretched hand, and at that moment Hugh died. He is buried in St John's churchyard in Keswick.[96]

Two full-length studies of Walpole were published after his death. The first, in 1952, was written by Rupert Hart-Davis, who had known Walpole personally. It was regarded at the time as "among the half dozen best biographies of the century"[126] and has been reissued several times since its first publication.[n 21] Writing when homosexual acts between men were still outlawed in England, Hart-Davis avoided direct mention of his subject's sexuality, so respecting Walpole's habitual discretion and the wishes of his brother and sister.[128] He left readers to read between the lines if they wished, in, for example, references to Turkish baths "providing informal opportunities of meeting interesting strangers".[129] Hart-Davis dedicated the book to "Dorothy, Robin and Harold", Walpole's sister, brother, and long-term companion.[130]

My published books: