Queer Places:

Barnard College (Seven Sisters), 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027

102 W 76th St, New York, NY 10023

Alwyn Court,

180 W 58th St, New York, NY 10019

Henrietta Walter “Ettie” Stettheimer (July 30, 1875 – June 1, 1955) was a writer, publishing under the

pseudonym Henrie Waste, a name drawn from her full name, Henrietta Walter

Stettheimer. She wrote “two highly wrought novels, Philosophy and Love

Days...that would certainly by today’s standards be considered feminist in

their insistence that woman’s self-realization is incompatible with romantic

love, and, in the case of Love Days, in the demonstration of the devastating

results of the wrong sort of amorous attraction.” In his brief essay, “My

Favorite Authors,” Carl Van Vechten praised Ettie Stettheimer’s writing and

added her to his list of favorites.

Henrietta Walter “Ettie” Stettheimer (July 30, 1875 – June 1, 1955) was a writer, publishing under the

pseudonym Henrie Waste, a name drawn from her full name, Henrietta Walter

Stettheimer. She wrote “two highly wrought novels, Philosophy and Love

Days...that would certainly by today’s standards be considered feminist in

their insistence that woman’s self-realization is incompatible with romantic

love, and, in the case of Love Days, in the demonstration of the devastating

results of the wrong sort of amorous attraction.” In his brief essay, “My

Favorite Authors,” Carl Van Vechten praised Ettie Stettheimer’s writing and

added her to his list of favorites.

The daughters of wealthy German Jews, the Stettheimer sisters were raised in Rochester, New York. Their father deserted the family when they were children and, after two older siblings married and moved away, the three sisters, Carrie, Ettie, and Florine, and their mother Rosetta Walter (1841-1935), became a close-knit family. Together with their mother, the Stettheimers lived and traveled in Europe for several years just after the turn of the century, often socializing with other expatriate Americans.

Ettie Stettheimer

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of My Sister Ettie Stettheimer, 1923

Florine Stettheimer, Family Portrait I, 1915. Art Properties, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York, New York. Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer, 1967

Florine Stettheimer, Family Portrait II, 1933. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer, 1956. Image provided by The Museum of Modern Art / SCALA / Art Resource, New York

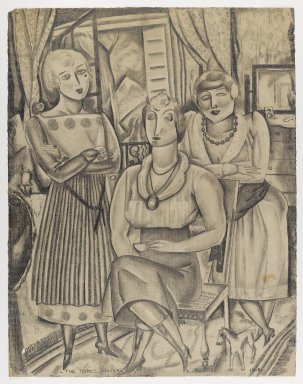

Florine, Carrie, and Ettie Stettheimer

Louis (George Louis Robert) Bouché (American, 1896-1969). The Three Sisters, 1918. Graphite on cream, moderately thick, moderately textured laid paper, sheet: 24 3/16 x 18 7/8 in. (61.4 x 47.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Ettie Stettheimer, 45.121 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 45.121_IMLS_PS4.jpg)

Stettheimer’s portrait of her younger sister Ettie places her in a dark, starlit setting in front of a combination burning bush-Christmas tree, perhaps to signify the family’s cultural assimilation as Jews who celebrated Christmas. Like Florine, the subject also appears to be floating in space, lounging on a red fainting couch. An ornament on the tree, a red book inscribed with the name “Ettie,” represents Ettie’s role as the author and intellectual of the family. All three Stettheimer sisters were extremely intelligent but Ettie was highly educated—collecting degrees at Columbia College, Barnard, and a Ph.D. at the University of Fribourg. To conceal her gender, Ettie authored novels under the pseudonym “Henrie Waste.”

When it became clear that World War I was approaching, the Stettheimers returned to the United States and moved to a house on New York’s Upper West Side. Shortly, their home became the premier New York salon, a center of the city’s artistic and intellectual life. Regular guests of the Stettheimer sisters included artists such as Francis Picabia, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and writers and critics, including Henry McBride and Carl Van Vechten. The sisters also regularly threw parties at rented mansions on the New Jersey shore or in the country, taking their friends away from the city for long weekends.

Ettie was the conversationalist of the family, witty and charming beyond compare. The Stettheimers were “an exotic if somewhat strange trio: Ettie in red wig, brocades, and diamonds; Carrie, who dressed never in the fashions of the day but in the elegance of a past era; Florine in white satin pants.” They were all extremely fashionable, though often they appeared as though they were of another age. Carrie was the hostess, managing the household and planning menus. The Stettheimer sisters typified the idea of the “new woman” of the twentieth century, they “declared men impossible but worthy of flirtation. They wore pants, smoked cigarettes, disdained marriage, romance and children, and were constantly surrounded by artists and writers who were drawn to their soigné gatherings.” They were also ladylike to a fault.

In addition to their friendships with many of the most significant artists and writers of the time, each of the sisters was involved in the arts in her own right. Florine Stettheimer was a painter, and she is, today, the best known of the family. During her lifetime, however, she only rarely exhibited her work publicly and refused to sell any of her paintings. Because of these limitations, her work was largely unknown for much of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, she received a great deal of attention for the innovative costumes and sets she designed for Four Saints in Three Acts, the Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson opera produced in 1934. Made in large part of cellophane, Stettheimer’s costumes and sets contributed to the “spirit of inspired madness” that permeated the production; her sets and costumes were described as “fantastically absurd.” Exhibitions of her paintings in recent years have introduced Florine Stettheimer’s work to new audiences. Her witty, insightful, and vibrant portraits of her family and friends, including her portrait of Carl Van Vechten in his apartment, reveal a compelling picture of the Stettheimers, their circle, and the times in which they lived.

In addition to the considerable artistry with which Carrie Stettheimer managed the Stettheimer household, planning imaginative meals including such unlikely dishes as feather soup, she created a replica of the sisters’ home in miniature—a remarkable two story, sixteen-room dollhouse that recreated the Stettheimer’s own imaginatively decorated rooms. Carrie Stettheimer worked on this project for more than twenty-five years, filling the dollhouse with detailed miniature reproductions of period furniture and replica light fixtures and lampshades. She recreated her sisters’ rooms—Ettie’s was painted in bright red and blue and outfitted with Chinese furniture; Florine’s was draped in cellophane and lace. Artist friends made small copies of their paintings and sculptures for the dollhouse including the miniature copy Marcel Duchamp made of his Nude Descending a Staircase. Carrie Stettheimer’s dollhouse is on permanent display at the Museum of the City of New York.

Carl Van Vechten and the Stettheimer sisters became close friends during the height of their salon in the days just after World War I. Van Vechten, in fact, dedicated his Sacred and Profane Memories to the sisters, a gesture that thrilled them all. Though Florine Stettheimer preferred not to be photographed, Carrie and Ettie were among Van Vechten’s earliest subjects and their double portraits are among the most unusual of all his compositions.

My published books: