Queer Places:

Langar Rectory, Church Ln, Langar, Nottingham NG13 9HG, Regno Unito

Shrewsbury School, Ashton Rd, Shrewsbury SY3 7BA, Regno Unito

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Clifford’s Inn, Chancery Ln, London WC2A 1PR, Regno Unito

St Paul Covent Garden, Bedford St, London WC2E 9ED, Regno Unito

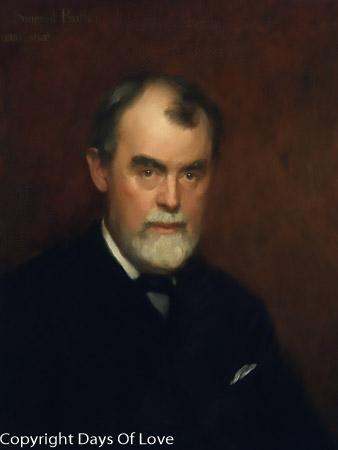

Samuel

Butler (4 December 1835 – 18 June 1902) was the iconoclastic English author of

the Utopian satirical novel Erewhon (1872) and the

semi-autobiographical Bildungsroman The Way of All Flesh, published

posthumously in 1903. Both have remained in print ever since. In other studies

he examined Christian orthodoxy, evolutionary thought, and Italian art, and

made prose translations of the Iliad and Odyssey that are still

consulted today. He was also an artist. Mr Emerson in

E.M. Forster's A Room with a View

(1908) is probably partly based on Butler.

Samuel

Butler (4 December 1835 – 18 June 1902) was the iconoclastic English author of

the Utopian satirical novel Erewhon (1872) and the

semi-autobiographical Bildungsroman The Way of All Flesh, published

posthumously in 1903. Both have remained in print ever since. In other studies

he examined Christian orthodoxy, evolutionary thought, and Italian art, and

made prose translations of the Iliad and Odyssey that are still

consulted today. He was also an artist. Mr Emerson in

E.M. Forster's A Room with a View

(1908) is probably partly based on Butler.

Butler never married, and although he did for years make regular visits to a woman, Lucie Dumas, he also "had a predilection for intense male friendships, which is reflected in several of his works."[11]

His first significant male friendship was with the young Charles Pauli, son of a German businessman in London, whom Butler met in New Zealand; they returned to England together in 1864 and took neighbouring apartments in Clifford's Inn. Butler had made a large profit from the sale of his New Zealand farm, and undertook to finance Pauli's study of law by paying him a regular pension, which Butler continued to do long after the friendship had cooled, until Butler had spent all of his savings. Upon Pauli's death in 1892, Butler was shocked to learn that Pauli had benefited from similar arrangements with other men and had died wealthy, but without leaving Butler anything in his will.[11][12]

After 1878, Butler became close friends with Henry Festing Jones, whom Butler persuaded to give up his job as a solicitor to be Butler's personal literary assistant and travelling companion, at a salary of £200 a year. Although Jones kept his own lodgings at Barnard's Inn, the two men saw each other daily until Butler's death in 1902, collaborating on music and writing projects in the daytime, and attending concerts and theatres in the evenings; they also frequently toured Italy and other favourite parts of Europe together. After Butler's death, Jones edited Butler's notebooks for publication and published his own biography of Butler in 1919.[11]

Langar Rectory

St. Paul's Church, London

Another significant friendship was with Hans Rudolf Faesch, a Swiss student who stayed with them in London for two years, improving his English, before departing for Singapore. Both Butler and Jones wept when they saw him off at the railway station in early 1895, and Butler subsequently wrote a very emotional poem, "In Memoriam H. R. F.",[13] instructing his literary agent to offer it for publication to several leading English magazines. However, once the Oscar Wilde trial began in the spring of that year, with revelations of homosexual behaviour among the literati, Butler feared being associated with the widely reported scandal and in a panic wrote to all the magazines, withdrawing his poem.[11] Tellingly, in his Memoir Jones describes this as a "Calamus poem"; both men would have been aware of Walt Whitman's homoerotic poems of the same name, as well as the very famous but less directly homoerotic In Memoriam by Alfred, Lord Tennyson lamenting the death of his friend Arthur Hallam. Jones adds that Butler chose that title because "he had persuaded himself that we should never see Hans again."[13]

Beginning with Malcolm Muggeridge in 1937, a number of literary critics have discussed Butler's sublimated or repressed homosexuality, comparing his lifelong pose as an "incarnate bachelor" to the very similar bachelorhoods among his contemporaries of other writers assumed to be homosexual but closeted, such as Walter Pater, Henry James, and E. M. Forster. As Herbert Sussman speculates:[14]

There can be little doubt as to the intensity of Butler's same-sex desire, and the intensity with which he deployed the bachelor mode to regulate it. Victorian bachelorhood enabled a middle-class man who rejected matrimony to remain distinctly middle-class.... For Butler, as for Pater and James, the aim of bachelordom was to contain the homoerotic within the respectable.... With Pauli, and with Jones and Faesch, Butler most likely kept within the homosocial boundaries of his time. There is no evidence of genital contact with other men, although the temptations of overstepping the line strained his close male relationships.

Regarding the visits to Lucie Dumas (Jones was also a client of hers, and Butler paid for his visits), Sussman says, "Even the scheduled excursions into heterosexual sex functioned less to relieve the sexual tension of bachelorhood than to act out the intense same-sex desire for one's daily companions.... In characteristic Victorian fashion, then, these men... perform[ed] their sexual bond through the body of a woman."[14]

My published books: