Queer Places:

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Ray

Strachey (born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe; 4 June 1887 – 16 July 1940)

was a British feminist

politician, mathematician, engineer, artist and writer.[1]

Her name and picture (and those of 58 other women and men's suffrage supporters)

are on the

plinth of the

statue of

Millicent Fawcett in

Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.

Ray

Strachey (born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe; 4 June 1887 – 16 July 1940)

was a British feminist

politician, mathematician, engineer, artist and writer.[1]

Her name and picture (and those of 58 other women and men's suffrage supporters)

are on the

plinth of the

statue of

Millicent Fawcett in

Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.

The suffragettes liaised with each other internationally through the League of Nations, the Women’s Freedom League, the British Commonwealth League and the Save the Children Fund. They also collaborated in expressing their political ideas through writing for journals such as Time and Tide edited by Margaret Haig, The Shield edited by Alison Neilans, the Woman’s Leader coedited by Elizabeth Macadam, and collaborated to write books such as Our Freedom and its Results by Five Women, edited by Ray Strachey and with contributions by Eleanor Rathbone, Ray Strachey, Erna Reiss, Alison Neilans and Mary Agnes Hamilton.

Strachey's father was Irish barrister Benjamin "Frank" Conn Costelloe, and her mother was art historian Mary Berenson. She was the elder of the two girls in her family. Her younger sister Karin Costelloe married Adrian Stephen, Virginia Woolf's younger brother, in 1914. Ray was educated at Kensington high school and at Newnham College, Cambridge, where she achieved third class in part one of the mathematical tripos (1908). Like some other female Mathematics graduates of the time, such as Margaret Dorothea Rowbotham and Margaret Partridge, Strachey developed an interest in engineering. She was discouraged by her mother Mary Berenson[2] but nevertheless she took an electrical engineering class at Oxford University in 1910[3] and planned to study electrical engineering at the Technical College of the City and Guilds of London Institute in October 1910. She wrote to her aunt "I have decided to go to London next winter for my engineering" and that she had been encouraged and helped by Hertha Ayrton.[3] She abandoned her plan due to marriage, but maintained her involvement with the Society of Women Welders which she had helped to found.[4]

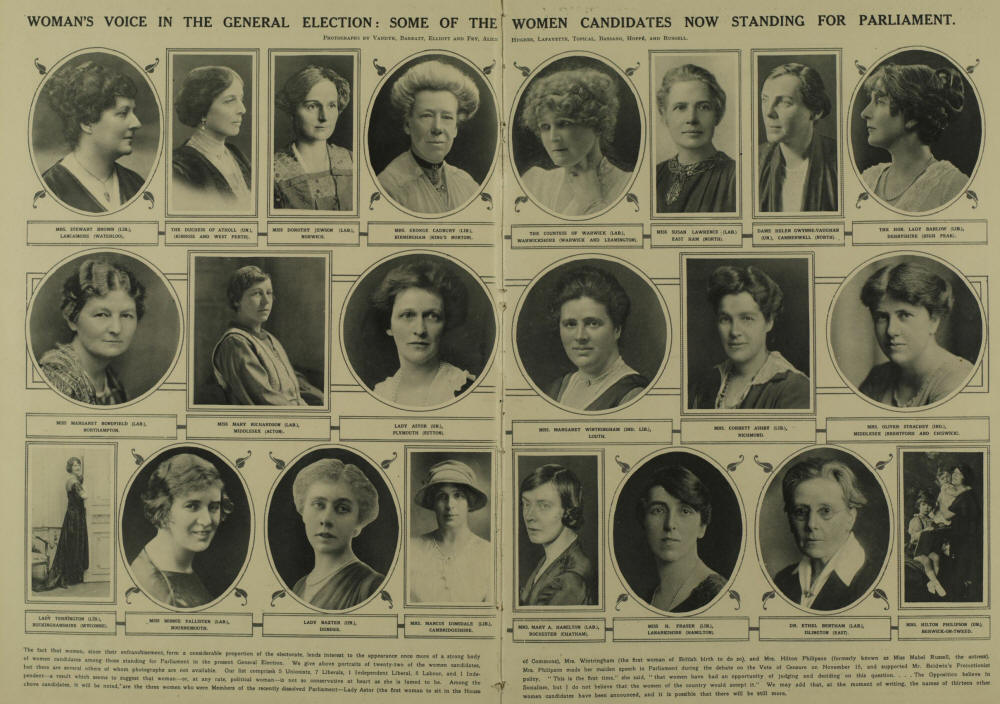

For most of her life, Strachey worked for women's suffrage organisations, starting when she was studying at Cambridge, when she joined what became known as the Mud March in February 1907 and addressing meetings in summer 1907.[2] She took part in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) Caravan tour in July 1908.[5] Most of Strachey's publications are non-fiction and deal with suffrage issues. She is most often remembered for her book The Cause (1928). Her papers are held at The Women's Library at the London School of Economics.[6] Strachey worked closely with Millicent Fawcett, sharing her Liberal feminist values and opposing any attempt to integrate the suffrage movement with the Labour Party. In 1915 she became parliamentary secretary of the NUWSS, serving in this role until 1920.[7] Strachey took great interest in the employment of women in engineering occupations. In 1919 women found themselves excluded by law from most jobs in the engineering industry under the Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act 1919. Strachey campaigned on behalf of the Society of Women Welders in 1920 for women to remain in the trade.[8] In 1922 Strachey also created a company to build small mud houses to help the housing shortage, based on a 1922 prototype known as "Copse Cottage". Women were employed to assemble them but there were problems with sourcing the correct clay and the chimney builders refused to co-operate. The Mavat company did exhibit a bungalow in 1925 at the Women's Arts & Crafts Exhibition at Central Hall in London. Strachey was defeated but she found work for all the women involved.[9] In her book Women's Suffrage and Women's Service[10] she described the setting up by the London Society for Women's Service of a school for Oxy-Acetylene Welding. In 1937 she wrote about women's employment in professional and trade roles in Careers and Openings for Women.[11] After the Great War, when some women were granted the vote, and women could stand for parliament, she stood as an Independent parliamentary candidate at Brentford and Chiswick on the General Elections in 1918, 1922 and 1923, without success. She rejected the attempt by Eleanor Rathbone to establish a broad-based feminist programme in the 1920s. In 1931 she became parliamentary secretary to Britain's first woman MP to take her seat, Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor, and in 1935 Strachey became the head of the Women's Employment Federation. She also made regular radio broadcasts for the BBC.

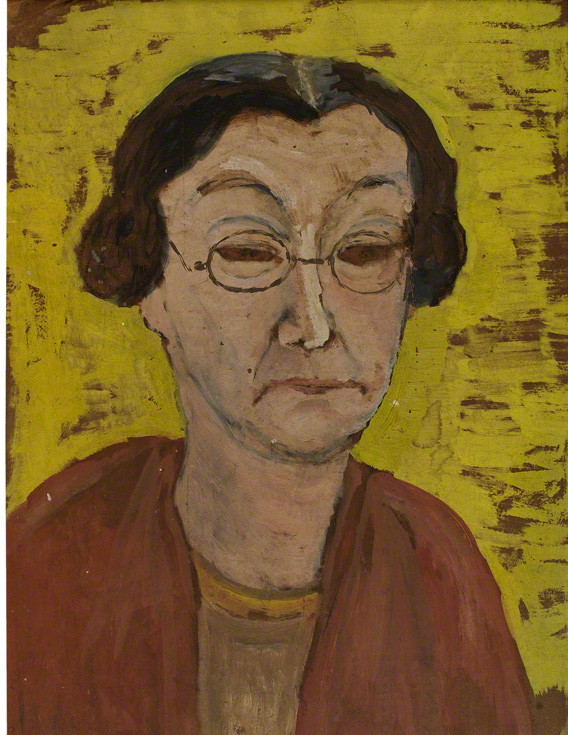

portrait of Pernel Strachey

by Ray Strachey; painted circa 1930

She married at Cambridge on 31 May 1911 the civil servant Oliver Strachey, with whom she had two children, Barbara (born 1912, later a writer) and Christopher (born 1916, later a pioneer computer scientist). Oliver Strachey was the elder brother of the biographer Lytton Strachey of the Bloomsbury group; other siblings in the Strachey family included psychoanalyst James Strachey, novelist Dorothy Bussy, educationist Pernel Strachey. Ray's mother-in-law was Jane Maria Strachey, a well-known author and supporter of women's suffrage who co-led the suffragist Mud March of 1907 in London.

Strachey painted her sister-in-law, Pernel Strachey, around the year 1930. Her painting is in the National Portrait Gallery in London.[13]

She died in the Royal Free Hospital in London in her early fifties of heart failure, following an operation to remove a fibroid tumor.[14]

My published books: