Queer Places:

Smith College (Seven Sisters), 9 Elm St, Northampton, MA 01063

New York University, 70 Washington Square S, New York, NY 10012

83 Washington Pl, New York, NY 10011

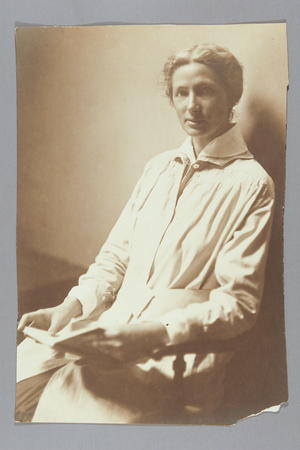

Madeleine Zabriskie Doty (August 24, 1877 – October 14, 1963) was an American journalist, pacifist, civil

libertarian, and advocate for the rights of prisoners, as well as the

International Secretary for the Women's International League for Peace and

Freedom. Beginning of the 1920s

Emily Greene Balch lived

and worked at the Maison International in Rue du Vieux Collège in Geneva, on

and off, for 12 years. During a Zürich meeting, she received a cable

terminating her 20-year-long academic job at Wellesley College, on the grounds

that she had been employed ‘to teach economics, not pacifism’. Left with no

means of support and no pension at the age of 52, Balch had celebrated her

dismissal by smoking a cigarette with

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

and the American lawyer Madeleine

Doty; along with its dislike of independent women, Wellesley had a strict

taboo on smoking.

Madeleine Zabriskie Doty (August 24, 1877 – October 14, 1963) was an American journalist, pacifist, civil

libertarian, and advocate for the rights of prisoners, as well as the

International Secretary for the Women's International League for Peace and

Freedom. Beginning of the 1920s

Emily Greene Balch lived

and worked at the Maison International in Rue du Vieux Collège in Geneva, on

and off, for 12 years. During a Zürich meeting, she received a cable

terminating her 20-year-long academic job at Wellesley College, on the grounds

that she had been employed ‘to teach economics, not pacifism’. Left with no

means of support and no pension at the age of 52, Balch had celebrated her

dismissal by smoking a cigarette with

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

and the American lawyer Madeleine

Doty; along with its dislike of independent women, Wellesley had a strict

taboo on smoking.

Madeleine Zabriskie Doty was born in Bayonne, New Jersey, August 24, 1877 to Samuel and Charlotte Zabriskie Doty.[1] She received a B.L. from Smith College in 1900, an L.L.B. from New York University in 1902, and a Ph.D. in International Relations from Geneva University in 1934.[2][1]

After practicing law for five years in New York City, her interest turned to children's courts and delinquency and for three years she was secretary of the Russell Srage Foundation Children's Court Committee. As a member of New York's Prison Reform Commission in 1913, she voluntarily spent a week in prison to investigate conditions, adopting Maggie Martin as her alias.[3] She described inhumane conditions in women's prisons, and advocated dramatic changes relating to prison management, prisoner autonomy, and prison activities. In addition to recommending improvements in food and sanitation, she advocated for the prisoners having a say in the way that the prisons were run. To that end, she proposed a system of prisoner self-government. [3] Out of this experience she published Society's Misfits (1916)[4] about juvenile and women's prison reform. After the publication of this text, New York State prison administrators experimented with some of her recommendations.[3]

Florence Harding and Madeleine Doty in Japan

Doty's pacifist principles placed her among an international circle of pacifist women who believed that women's exclusion from war-making councils gave them an objective view which made them more natural peacemakers than men. In 1915, with Jane Addams and forty-three other women from the U.S., she attended the Women's Peace Congress at The Hague. On this journey, she represented the Women’s Lawyers Association and worked as a reporter for Century Magazine and a special correspondent for the New York Evening Post.[5] She then became a correspondent for the New York Tribune and Good Housekeeping.[6] She reported from Hamburg, Germany for the Tribune in 1916,[7] and reported that it was "like a dying city" as the citizens were starving.[1] For Good Housekeeping, she traveled around the world and was in Russia during the 1917-1918 revolution. She published Short Rations: An American Woman In Germany[8] in 1917 and Behind The Battle Line[9] in 1918.

On her return to the U.S. in 1917, Doty became an editor with her friend Crystal Eastman of Four Lights, the radical paper of the New York Woman’s Peace Party. In a letter on January 13, 1917, to Dr. Maria Montessori, Fannie May Witherspoon, a Christian socialist and another co-editor of Four Lights, described the purpose of the paper as “striking what seems to us a much-needed note of internationalism in these days of universal warfare and national strife ... the contributors will be chiefly women, and the issues of feminism and peace will naturally go hand in hand.”[5] Reporting war news from a feminist and pacifist lens, it published articles featuring a “gender-based critique of American society and democracy.”[10] Doty continued to play a part in the peace movement first as International Secretary for the WILPF in Geneva, where she moved in 1925,[1] then as editor of Pax International for the League of Nations.

In 1919 she married pacifist Roger Baldwin, who later founded the ACLU.[11] Doty had been Crystal Eastman's roommate, which is how she met Baldwin. Doty and Baldwin literally vowed to maintain a "free marriage," with neither requiring monogamy of the other.[12] Doty retained her maiden name, had an active public career, supported herself financially, and employed a domestic servant to manage the reproduction of the household.[13] However, they were divorced in 1925.

In 1936, foreseeing the collapse of the League, Doty decided that the only way to secure world peace was through education of the young. She created and organized the first Geneva Junior Year Abroad program for the University of Delaware, 1938-1939. Because it was impossible to continue during World War II, she studied at the University of Geneva, receiving a Ph.D in International Relations in 1945 at the age of 66. After the war she returned to the U.S. and between 1946 and 1949 she organized and ran another Geneva Junior Year Abroad program for Smith College.[2] Beginning in 1950 Doty taught history at Miss Harris's School in Florida. She retired at the age of 75. She returned to Geneva and lectured on American history at the University of Geneva until 1962 when she moved to Greenfield, Massachusetts, where she died October 14, 1963.[1]

My published books: