Queer Places:

6803 W Roosevelt Rd, Oak Park, IL 60304

John Joseph Kriza Jr. was born in Berwyn, a suburban city west of Chicago, in Cook County, Illinois. The son of Czech immigrants, he grew up in Bloomingdale on his parents' farm and attended J. Sterling Morton High School in Berwyn. He became well known in the community for his ballet achievements. At the urging of his mother, who was concerned for the health of her underweight son, he had begun his dance studies at age seven, first with Mildred Prehal, a local teacher, and then with Bentley Stone and Walter Camryn in Chicago. Some years later, after relocating to New York, he studied with Pierre Vladimiroff at the School of American Ballet and with Anton Dolin and Valentina Pereyslavic at the Ballet Theatre School.[2]

Kriza received his professional start from Ruth Page, the grande dame of ballet in Chicago, who hired him in 1938 for the Federal Dance Project, part of President Roosevelt's Second New Deal.[3] In 1939 he toured South America with the Page-Stone Ballet, and in 1940 he settled in New York. After a brief stint on Broadway, where he appeared inn Panama Hattie (1941), with music by Cole Porter and dances by Robert Alston, he joined American Ballet Caravan, a company recently formed by George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein. With this troupe, he created his first role in Antony Tudor's Time Table, as one of a group of soldiers in a train station saying goodbye to their girlfriends. He then joined Ballet Theatre, another new company, formed in 1939 by Richard Pleasant and Lucia Chase with a small group of dancers from the Mordkin Ballet. He remained with this company, renamed American Ballet Theatre in 1965, for twenty-five years, creating many important roles and participating in many historic events.[4]

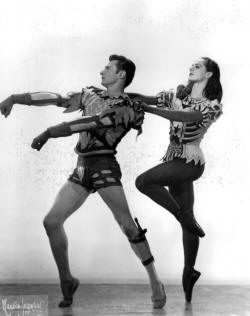

Over the years, Kriza accumulated a vast and diverse repertory of roles.[5] His most celebrated part was the title character of Eugene Loring's Billy the Kid, with music by Aaron Copland and a story based on episodes from the life of the notorious but peculiarly appealing desperado of the Old West. Kriza also danced leading roles in Agnes de Mille's Rodeo, Tally-Ho, and Rib of Eve; Michel Fokine's Les Sylphides, Petrouchka, Bluebeard, and Helen of Troy; and Antony Tudor's Romeo and Juliet, Jardin aux Lilas, Dark Elegies, and Offenbach in the Underworld. In the 1945 season, one critic noted that "Kriza, overworked as he was, was everywhere Ballet Theatre's brightest mainstay, and his verve in his final Romeo woke up Zlatkin [the conductor] and the orchestra to a fine musical performance and almost woke up Miss Markova out of her season's trance."[6] Kriza was sometimes called "Mr. Ballet Theatre" because of his wide range of roles, his frequent appearances, and his singular popularity with audiences. He was admired in roles both tragic and lighthearted. In The Combat, an intensely dramatic work by William Dollar, set to music by Raffaello de Banfield, Kriza danced the Christian knight Tancredi opposite Melissa Hayden as Clorinda, a Saracen girl, to powerful effect, as he kills her in a duel, unaware of her identity. (Lupe Serrano was also a stunning partner/opponent in this piece.) In stark contrast, Kriza also appeared as the cheeky Boy in Green in Frederick Ashton's Les Patineurs and as the strutting Drummer in David Lichine's Graduation Ball. In both these roles, he was praised for "his wonderful sense of tongue-in-cheek drollery," which made his performances "a delight."[7] In the classical repertory, he danced the merry suitor Colin in a version of La Fille Mal Gardée as well as the princely roles of Albrecht in Giselle. Siegfried in Swan Lake, and Prince Désiré in Aurora's Wedding.[8]

Particularly noted for his dramatic abilities, Kriza also embodied a distinctly American style of dancing. Although not a classical virtuoso, he was praised for his lyrical and poetic qualities. He had sufficient command of classical technique to dance a credible Blue Bird in Aurora's Wedding and a brilliant It Was Spring in Dim Lustre, a dream sequence of "the memory of a boy who kissed her on a day in Spring when she was very young."[9] Early in his career, in May 1945, Kriza was singled out for praise by Edwin Denby, a noted critic, who wrote "Kriza has now a straight, free sweep and clarity of movement, a fine posture, and a friendly modesty of manner that are all first-rate. . . . In Wednesday's Fancy Free he danced his solo with a sudden instinct for continuity of phrasing that showed very sharply his rich real gifts as a dancer."[10] Of a 1956 revival of Billy the Kid, New York Times critic John Martin wrote "John Kriza's ever the ingratiating personality, the expert partner, and the delightful actor-dancer when he has a role that will allow. His Billy the Kid this season was fresh once more and full of authority."[11]

After retiring from the stage in 1966, Kriza served for several years as assistant to American Ballet Theatre's directors. He continued to coach revivals of ballets for various companies and to teach. During the 1970s, he was on the dance faculty of the Indiana University at Bloomington. His last public appearance was at American Ballet Theatre's thirty-fifth-anniversary gala in January 1975, when he joined Jerome Robbins and Harold Lang on stage after a performance of Fancy Free, bringing the three original Sailors together again. While visiting his sister and her husband in Naples, Florida, Kriza drowned while swimming in the sea near their home. He was found dead on the morning of 18 August 1975, floating in the Gulf of Mexico. He was 56 years old.[12]

My published books: