Partner Richard Riley

Queer Places:

Craxton Studios, 14 Kidderpore Ave, London NW3 7SU, UK

Abercorn Mansions, 17 Abercorn Pl, London NW8 9DY, UK

John Craxton (October

3, 1922 - November 17, 2009) was a luminary of the Neo-Romantic movement of the 1930s and early 1940s, which sought to depict not so much the events and characters of heroic myths – and the pastoralism of historical past – as to evoke an atmosphere of a pre-industrial age, at times bucolic and primeval, by using milder forms of pictorial Modernism. Like

Lucian Freud (with whom he had a close but short friendship), Craxton was another well-connected boy wonder in London’s constricted wartime cultural scene.

John Craxton attracted the interest of the authorities in Greece after the

military coup in April 1967: ‘Espionage was already suspected, since the

liking of so cultivated a man for sailors’ bars must surely signal an interest

in naval intelligence. That raised a laugh from the suspect.’

John Craxton (October

3, 1922 - November 17, 2009) was a luminary of the Neo-Romantic movement of the 1930s and early 1940s, which sought to depict not so much the events and characters of heroic myths – and the pastoralism of historical past – as to evoke an atmosphere of a pre-industrial age, at times bucolic and primeval, by using milder forms of pictorial Modernism. Like

Lucian Freud (with whom he had a close but short friendship), Craxton was another well-connected boy wonder in London’s constricted wartime cultural scene.

John Craxton attracted the interest of the authorities in Greece after the

military coup in April 1967: ‘Espionage was already suspected, since the

liking of so cultivated a man for sailors’ bars must surely signal an interest

in naval intelligence. That raised a laugh from the suspect.’

Early in WWII, Peter Watson had arranged a studio for the Scottish painters Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde (they were known as "the two Roberts" because they were a couple.) Later he provided support to John Craxton, Michael Wishart, and Lucien Freud. Dwight Ripley joined in this project, if marginally, when he bought an oil by MacBryde and lent it to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

His father was a Harold Craxton who was a pianist, accompanist, and teacher. His five siblings included the distinguished oboist Janet Craxton and the BBC’s Royal events television director Antony Craxton C.V.O. According to Ian Collins’s new biography John Craxton: A Life of Gifts (not to be confused with a separate 2011 monograph on Craxton by Collins), Craxton had an unsettled childhood and a patchy education, spending time in Sussex, Dorset and elsewhere. He visited Paris in 1939 in search of contact with modern art and attended the Louvre. He took a few classes at the Académie Julian but was essentially self-taught. He was picked up by a publisher in 1940 and his Neo-Romantic illustrations provided him with an entry into the art world. Influenced by Samuel Palmer, Craxton’s early works are monochrome drawings and graphics on paper with paint in muted colours; they feature figures in densely drawn landscapes.

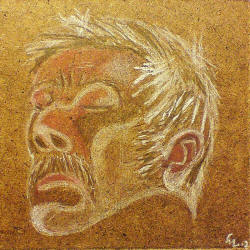

john craxton head of a greek sailor 1940

Craxton was part of the (not exclusively homosexual) circle around millionaire collector Peter Watson in that setting that included Freud, Cyril Connolly, Francis Bacon, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, John Minton and Kenneth Clark. Craxton was homosexual himself and – like many in the Fitzrovia/Soho sets – did not disguise the fact. Craxton fell in with Freud, a contemporary misfit and another enfant terrible of the Fitzrovia set. They met in 1941 and became inseparable until 1947. Both were engaged by pastoral landscapes and the figure, made portraits, admired realism but produced faux naïf art. Collins recounts with élan the pair’s hijinks in bombed London. They worked side by side in their shared Abercorn Place flat, sometimes working on pictures together, sometimes drawing each other. Their styles and subjects overlapped noticeably and it is hard to distinguish a leader and a follower. Later, some of the works in Craxton’s possession were sold as Freuds, much to the latter’s displeasure.

Watson paid for Craxton to attend life-drawing classes at Goldsmiths College. When he taught there unhappily and unsuccessfully, for only a term. The future art forger Tom Keating responded badly to being corrected by him. Craxton and Freud worked alongside Sutherland on the South Wales coast. Craxton’s range was expanding from ink drawing to conté-and-white-chalk on tinted paper (animal still-lifes, very close to Freud’s) and oil paintings. These have slightly less intensity and detail than Freud’s but have better overall composition and cropping and are slightly more pleasing as pictures.

The Greece that Craxton first visited in 1946 had not begun recovering from war, occupation and civil war. There was a civil war between nationalists and communists ongoing at the time, which would eventually see the communists defeated. Craxton had already acquired an affinity for Greek cuisine in Soho and thought that a hot dry climate would help his health. (Unbeknownst to him, he had contracted pulmonary tuberculosis in London, the cause of constant weakness and inability to put on weight.) The sunshine and good food of Greece inspired Craxton the man, restoring him to health. His new surroundings were immediately evident in his paintings of coastal views, still-lifes, landscapes and figures (mainly sailors, objects of attraction). His landscapes are heavily derived from early Miró.

Craxton went to Poros – lauded by Lawrence Durrell, George Seferis and Henry Miller – where Freud joined him in September 1946. “Lucian would remain in Greece for five months during which he produced the most beautiful work of his life. John never really left, in every sense finding himself in Greece.” Freud painted Craxton and himself, largely deprived of portrait subjects, and made still-lifes of fruit. Craxton was painting simplified townscapes, using the smooth surfaces and subtle brushwork the pair liked. They tapped Lady Norton, wife of diplomat Sir Clifford Norton, in order to sustain themselves in necessities.

Planning a joint exhibition of their Greek art, the pair returned to London in time for the severest winter of the century in Britain, exacerbated by a chronic fuel shortage. Craxton went to Crete in autumn 1947 and responded strongly to the mixture of Greek culture and Minoan art and architecture. Craxton mingled with shepherds and lived in the mountains; he also courted danger by seeking out bandits. Crete would become the centre of his imaginative world and he would henceforth live and work in Crete and London.

The London Gallery showed Craxton and Freud together and separately. Craxton sold well and was more prolific than Freud. Craxton’s scenes of Mediterranean life offered the deprived, ration-bound residents of Great Britain a sunny escape. Wyndham Lewis thought his pictures to be lightweight: “a prettily tinted cocktail, that’s good but does not quite kick hard enough.” While Craxton’s Picasso-inflected art of scenes and people of the sunny South struck a chord and found collectors, they came be viewed as increasingly out of step with the age of Existentialism and the Geometry of Fear.

In 1951 Frederick Ashton invited Craxton to design the set for the Covent Garden production of Ravel’s ballet Daphnis and Chloë. Craxton formed a close but short-lived friendship with lead ballerina Margot Fonteyn, who visited Crete, accompanied by Ashton. The production was considered cutting edge for its modern dress and décor, only receiving full appreciation after it had closed.

Craxton settled in Chania, a port on the coast of Crete. In 1955, Craxton’s penchant for sailors caught him out. He was accused of being a spy who had informed on a gun-running operation to Cyprus. As a foreign bohemian who travelled to London frequently, had links to the British Embassy and caroused with Greek naval men, Craxton was an obvious suspect. It was not true but the suspicion lingered even after his death. Craxton came to speak demotic Greek well and became involved in preserving Cretan heritage, which was disregarded by locals, especially when buildings dated to the Muslim occupation. Once he was suspected of harbouring antiquities. Craxton announced, “I have absolutely nothing Greek (ie antiquities) in the house except men and wine.”

Exhibitions at Mayor and Leicester galleries met collector demand. His art developed modestly. The curvilinear style that Picasso and Braque used was also found in Minoan murals. The mixture of Modernism and ancient art turned to decorative ends also incorporated Pop Art. The Butcher (1964-6) shows the influence of Patrick Caulfield, Pop Art and hard-edge abstraction, with its emphatic straight outlines and planes of uninflected strong colour. Breaking up surfaces into parallel lines of alternating colour (such as Two Figures and Setting Sun (1952-67)) the appearance of a tapestry. It is not coincidental that at this time Craxton was examining Byzantine mosaics.

His apparently impressive retrospective in 1967 at the Whitechapel Art Gallery confirmed his ability and the pleasure-giving capacity of his art and also his definitive distance from the critical consensus and fashion. During the Greek military junta (1967-74) Craxton went into exile, considered an undesirable by the regime. He wandered the ports of the Mediterranean in search of a substitute utopia. In 1973 a compensation came in the form of Richard Riley, who became his romantic partner for the rest of Craxton’s life.

When a group of drawings by Craxton and Freud surfaced, Freud disputed them, claiming they had been tampered with. He threatened the gallery with a lawsuit but the exhibition went ahead in 1984. The friendship, which had become distant over the years, was now dead. Freud’s capacity for grudge-bearing and feud-starting was legendary. Although the exhibition was a success, Craxton was hurt by Freud’s anger and Freud’s cutting remarks lingered in his mind until he died, according to friends.

However satisfying the art from the 1940s and 1950s is, one might find a lack of development in Craxton’s production disappointing. He was ultimately somewhat conservative in nature and timid. In his Neo-Romantic work, we see Samuel Palmer resuscitated with Miró and Picasso – all of whom laid out the styles and devices Craxton would use. It is true that not all artists must be original to be dazzling or wonderful, but greatness requires an essential forcefulness and daring, which Craxton lacked. Anyone painting in the 2000s as he did in the 1950s is someone who has the temperament of an artisan rather than an artist.

Another travail of old age was the incident when Craxton was drugged and thieves stole art from his house – including a Miró and a Sutherland. The thieves did not take any Craxtons. “Never losing a sense of humour, he claimed to have been not only robbed but insulted.” His final years were spent in London, where he died in 2009. His ashes were taken to Crete. Shortly before his death, he consented to be interviewed by Ian Collins for this biography and a monograph on his art. Collins has done well to search out personal acquaintances and track down photographs of the art, artist and his circle.

Elements of Craxton the painter remain a little elusive. Did Craxton write statements about his art, have a diary or pen useful letters? How productive was he? Did he destroy much? Did he disavow or criticise any of his work? What was his taste in art made by others? Although Collins adds a little near the end about Craxton’s routine and practices, readers may wish for more time inside the artist’s studio and his head. Yes, the art is enjoyable but did Craxton have strong ideas about what art – specifically his art – should do and not do?

These cavils should not deter anyone interested in Craxton and his art from reading this thoroughly researched, attractive and vivid biography.

My published books: