Queer Places:

Paultons House, Paultons Square, Chelsea SW3 5DU

St. Matthew's Church

Cheriton Fitzpaine, Mid Devon District, Devon, England

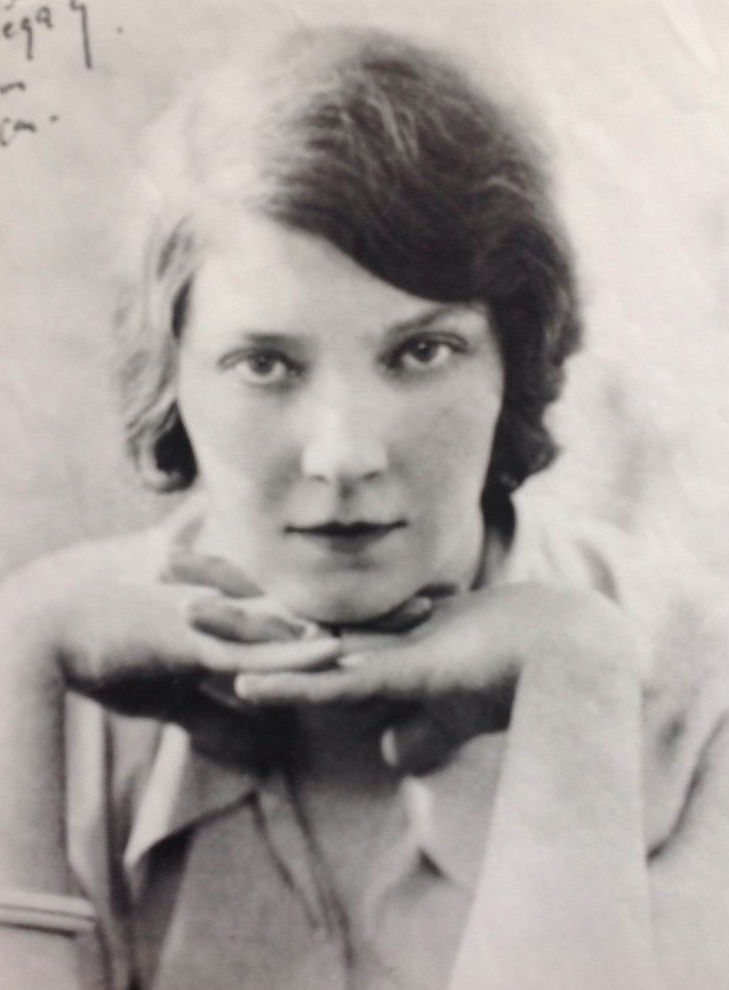

Jean

Rhys, CBE (born Ella Gwendolyn Rees Williams (24 August 1890 – 14 May 1979),

was a mid-20th-century novelist who was born and grew up in the Caribbean

island of Dominica. From the age of 16, she was mainly resident in England,

where she was sent for her education. She is best known for her novel Wide

Sargasso Sea (1966), written as a prequel to

Charlotte

Brontë's Jane Eyre.[4]

In 1978 she was awarded the Order of the British Empire for her writing. Shari

Benstock's Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940, is a study devoted

principally to thoughtful biographical and literary analyses of some 22 women: Margaret Anderson,

Djuna Barnes,

Natalie Barney,

Kay Boyle,

Sylvia Beach,

Bryher,

Colette, Caresse Crosby,

Nancy Cunard,

Hilda Doolittle,

Janet Flanner,

Jane Heap,

Maria Jolas,

Mina

Loy, Adrienne Monnier,

Anais Nin,

Jean Rhys,

Solita Solano,

Gertrude Stein,

Alice B. Toklas,

Renee Vivien, and

Edith Wharton, who came to dominate the

landscape of the modernist literary experiment in Paris.

Jean

Rhys, CBE (born Ella Gwendolyn Rees Williams (24 August 1890 – 14 May 1979),

was a mid-20th-century novelist who was born and grew up in the Caribbean

island of Dominica. From the age of 16, she was mainly resident in England,

where she was sent for her education. She is best known for her novel Wide

Sargasso Sea (1966), written as a prequel to

Charlotte

Brontë's Jane Eyre.[4]

In 1978 she was awarded the Order of the British Empire for her writing. Shari

Benstock's Women of the Left Bank: Paris, 1900-1940, is a study devoted

principally to thoughtful biographical and literary analyses of some 22 women: Margaret Anderson,

Djuna Barnes,

Natalie Barney,

Kay Boyle,

Sylvia Beach,

Bryher,

Colette, Caresse Crosby,

Nancy Cunard,

Hilda Doolittle,

Janet Flanner,

Jane Heap,

Maria Jolas,

Mina

Loy, Adrienne Monnier,

Anais Nin,

Jean Rhys,

Solita Solano,

Gertrude Stein,

Alice B. Toklas,

Renee Vivien, and

Edith Wharton, who came to dominate the

landscape of the modernist literary experiment in Paris.

Rhys was born in Roseau, the capital of Dominica, one of the British Leeward Islands. Her father, William Rees Williams, was a Welsh doctor and her mother, Minna Williams, née Lockhart, was a third-generation Dominican Creole of Scots ancestry. ("Creole" was broadly used in those times to refer to any person born on the island, whether they were of European or African descent, or both.) She had a brother. Her mother's family had an estate, a former plantation, on the island.

Rhys was educated in Dominica until the age of 16, when she was sent to England to live with an aunt, as her relations with her mother were difficult. She attended the Perse School for Girls in Cambridge,[5] where she was mocked as an outsider and for her accent. She attended two terms at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London by 1909. Her instructors despaired of her ever learning to speak "proper English" and advised her father to take her away. Unable to train as an actress and refusing to return to the Caribbean as her parents wished, Williams worked with varied success as a chorus girl, adopting the names Vivienne, Emma or Ella Gray. She toured Britain's small towns and returned to rooming or boarding houses in rundown neighbourhoods of London.[5]

After her father died in 1910, Rhys appeared to have experimented with living as a demimondaine. She became the mistress of wealthy stockbroker Lancelot Grey Hugh Smith, whose father Hugh Colin Smith had been Governor of the Bank of England.[6] Though a bachelor, Smith did not offer to marry Rhys, and their affair soon ended. However, he continued to be an occasional source of financial help. Distraught by events, including a near-fatal abortion (not Smith's child), Rhys began writing and produced an early version of her novel Voyage in the Dark.[5] In 1913 she worked for a time in London as a nude model.

During the First World War, Rhys served as a volunteer worker in a soldiers' canteen. In 1918 she worked in a pension office.

In 1919 Rhys married Willem Johan Marie (Jean) Lenglet, a French-Dutch journalist, spy and songwriter. He was the first of her three husbands.[5] She and Lenglet wandered through Europe. They had two children, a son who died young and a daughter. They divorced in 1933, and her daughter lived mostly with her father.

TThe next year Rhys married Leslie Tilden-Smith, an English editor. In 1936 they went briefly to Dominica, the first time Rhys had returned since she had left for school. She found her family estate deteriorating and island conditions less agreeable. Her brother Oscar was living in England, and she took care of some financial affairs for him, making a settlement with an island mixed-race woman and Oscar's illegitimate children by her.

In 1937 Rhys began a friendship with novelist Eliot Bliss (who had taken her first name in honour of two authors she admired). The two women shared Caribbean backgrounds. The correspondence between them survives.[7]

In 1939 Rhys and Tilden-Smith moved to Devon, where they lived for several years. He died in 1945. In 1947 Rhys married Max Hamer, a solicitor who was a cousin of Tilden-Smith. He was convicted of fraud and imprisoned after their marriage.[8] He died in 1966.

In 1924 Rhys came under the influence of English writer Ford Madox Ford. After meeting Ford in Paris, Rhys wrote short stories under his patronage. Ford recognised that her experience as an exile gave Rhys a unique viewpoint, and praised her "singular instinct for form". "Coming from the West Indies, [Ford] declared, 'with a terrifying insight and... passion for stating the case of the underdog, she has let her pen loose on the Left Banks of the Old World'."[5] This he wrote in his preface to her debut short story collection, The Left Bank and Other Stories (1927).

It was Ford who suggested she change her name from Ella Williams to Jean Rhys.[9] At the time her husband was in jail for what Rhys described as currency irregularities.

Rhys moved in with Ford and his long-time partner, Stella Bowen. An affair with Ford ensued, which she portrayed in fictionalised form in her novel Quartet (1928)[9] Her protagonist is a stranded foreigner, Marya Zelli, who finds herself at the mercy of strangers when her husband is jailed in Paris. Quartet's 1981 Merchant Ivory film adaptation starred Maggie Smith, Isabelle Adjani, Anthony Higgins, and Alan Bates.

In After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie (1931) the protagonist, Julia Martin, is a more unravelled version of Marya Zelli, romantically dumped and inhabiting the sidewalks, cafes and cheap hotel rooms of Paris.

With Voyage in the Dark (1934), Rhys continued to portray a mistreated, rootless woman. Here the narrator, Anna, is a young chorus girl who grew up in the West Indies and feels alienated in England.

Good Morning, Midnight (1939) is often considered a continuation of Rhys's first two novels. Here she uses modified stream of consciousness to voice the experiences of an ageing woman, Sasha Jansen, who drinks, takes sleeping pills and obsesses over her looks, and is adrift again in Paris. Good Morning, Midnight, acknowledged as well written but deemed depressing, came as World War II broke out and readers sought optimism. This seemingly ended Rhys's literary career.

In the 1940s Rhys largely withdrew from public life. From 1955 to 1960 she lived in Bude, Cornwall, where she was unhappy, calling it "Bude the Obscure", before moving to Cheriton Fitzpaine in Devon.

After a long absence from the public eye she was rediscovered by Selma Vaz Dias, who in 1949 placed an advertisement in the New Statesman asking about her whereabouts, with a view to obtaining the rights to adapt her novel Good Morning Midnight for radio. Rhys responded, and thereafter developed a long-lasting and collaborative friendship with Vaz Dias, who encouraged her to start writing again. This encouragement ultimately led to the publication in 1966 of her critically acclaimed novel Wide Sargasso Sea. She intended it as an account of the woman whom Rochester married and kept in his attic in Jane Eyre. Begun well before she settled in Bude, the book won the notable WH Smith Literary Award in 1967. She returned to themes of dominance and dependence, especially in marriage, depicting the mutually painful relationship between a privileged English man and a Creole woman from Dominica made powerless on being duped and coerced by him and others. Both the man and the woman enter marriage under mistaken assumptions about the other partner. Her female lead marries Mr Rochester and deteriorates in England as the "madwoman in the attic". Rhys portrays this woman from a quite different perspective from the one in Jane Eyre. Diana Athill of André Deutsch gambled on publishing Wide Sargasso Sea. She and the writer Francis Wyndham helped to revive interest in Rhys's work.[10]

In 1968 André Deutsch published a collection of Rhys's short stories, Tigers Are Better-Looking, of which eight were written during her 1950s period of obscurity and nine republished from her 1927 collection The Left Bank and Other Stories. Her 1969 short story I Spy a Stranger, published by Penguin Modern Stories, was adapted for TV in 1972 starring Mona Washbourne, Noel Dyson, Hanah Maria Pravda and Basil Dignam.[11][12] In 1976 André Deutsch published another collection of her short stories, Sleep It Off Lady, consisting of 16 pieces from an approximately 75-year period, starting from the end of the 19th century.

From 1960, and for the rest of her life, Rhys lived in Cheriton Fitzpaine, a small village in Devon that she once described as "a dull spot which even drink can't enliven much."[13] Characteristically, she remained unimpressed by her belated ascent to literary fame, commenting, "It has come too late."[10] In an interview shortly before her death she questioned whether any novelist, not least herself, could ever be happy for any length of time: "If I could choose I would rather be happy than write... if I could live my life all over again, and choose...."[14]

Jean Rhys died in Exeter on 14 May 1979, at the age of 88, before completing an autobiography, which she had begun dictating only months earlier.[15][16] In 1979 the incomplete text was published posthumously under the title Smile Please: An Unfinished Autobiography.

In 2012 English Heritage marked her Chelsea flat at Paulton House in Paultons Square with a blue plaque.[19]

Rhys's collected papers and ephemera are housed in the University of Tulsa's McFarlin Library.[20] The British Library acquired a selection of Jean Rhys Papers in 1972, including drafts of short stories, novels; After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, Voyage in the Dark, and Wide Sargasso Sea, and an unpublished play entitled English Harbour.[21] Research material relating to Jean Rhys can also be found in the Archive of Margaret Ramsey Ltd at the British Library relating to stage and film rights for adaptions to her work.[22]

My published books: