Queer Places:

Eton College, Windsor SL4 6DW, Regno Unito

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Britannia Royal Naval College, Manxman DIV St Vincent Sqdn, Brnc, Dartmouth TQ6 0HJ, Regno Unito

Lockers Park School, Lockers Park Ln, Hemel Hempstead HP1 1TL, Regno Unito

The Langham, 1C Portland Pl, Marylebone, London W1B 1JA, Regno Unito

5 Bentinck St, Marylebone, London W1U 2EG, Regno Unito

St John the Evangelist, 2 Court Farm Cottages, West Meon, Petersfield GU32 1JE, Regno Unito

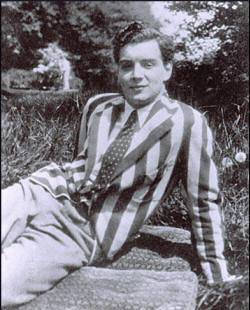

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British

diplomat and Soviet agent, a member of the

Cambridge Five spy ring that

operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era. His

defection in 1951 to the Soviet Union, with his fellow-spy

Donald Maclean,

led to a serious breach in Anglo-United States intelligence co-operation, and

caused long-lasting disruption and demoralisation in Britain's foreign and

diplomatic services. He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. The item on ‘Homosexuality’ in Norman Polmar and Thomas

B. Allen’s generally reliable Encyclopedia of Espionage (1998) names just nine

homosexual men and one bisexual: Alfred

Redl, Guy Burgess, the bisexual

Donald Maclean,

Anthony Blunt,

Alan Turing,

James A. Mintkenbaugh,

William Martin,

Bernon Mitchell,

John Vassall and

Maurice Oldfield. The

last-named had to resign his position as co-ordinator of UK security and

intelligence in Northern Ireland after he was found to be homosexual; there

was no suggestion that in his previous incarnation as Director General of MI6

he ever spied for anyone but his own Whitehall masters.

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British

diplomat and Soviet agent, a member of the

Cambridge Five spy ring that

operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era. His

defection in 1951 to the Soviet Union, with his fellow-spy

Donald Maclean,

led to a serious breach in Anglo-United States intelligence co-operation, and

caused long-lasting disruption and demoralisation in Britain's foreign and

diplomatic services. He was part of the

Cambridge Apostles. The item on ‘Homosexuality’ in Norman Polmar and Thomas

B. Allen’s generally reliable Encyclopedia of Espionage (1998) names just nine

homosexual men and one bisexual: Alfred

Redl, Guy Burgess, the bisexual

Donald Maclean,

Anthony Blunt,

Alan Turing,

James A. Mintkenbaugh,

William Martin,

Bernon Mitchell,

John Vassall and

Maurice Oldfield. The

last-named had to resign his position as co-ordinator of UK security and

intelligence in Northern Ireland after he was found to be homosexual; there

was no suggestion that in his previous incarnation as Director General of MI6

he ever spied for anyone but his own Whitehall masters.

Born into a wealthy middle-class family, Burgess was educated at Eton College, the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth and Trinity College, Cambridge. An assiduous networker, he embraced left-wing politics at Cambridge and joined the Communist Party. He was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935, on the recommendation of Kim Philby. Jack Macnamara was a Member of Parliament (MP) for Chelmsford. Macnamara's personal assistant in 1935–36 was Guy Burgess. Macnamara was a member of the Anglo-German Fellowship, some of whose members were pro-Nazi. Burgess gained the confidence of Macnamara and they organized a series of sex tours abroad, especially to Germany where Macnamara had ties with the Hitler Youth. Burgess managed to gain contacts with highly placed homosexuals, like Edouard Pfeiffer, the chief private secretary of Édouard Daladier, French War Minister, an agent of the 2nd Office and of MI6. Macnamara and Burgess were invited on several occasions to pleasure parties at Pfeiffer's or to Parisian nightclubs.

After leaving Cambridge, Burgess worked for the BBC as a producer, briefly interrupted by a short period as a full-time MI6 intelligence officer, before joining the Foreign Office in 1944.At the Foreign Office, Burgess acted as a confidential secretary to Hector McNeil, the deputy to Ernest Bevin, the Foreign Secretary. This post gave Burgess access to secret information on all aspects of Britain's foreign policy during the critical post-1945 period, and it is estimated that he passed thousands of documents to his Soviet masters. In 1950 he was appointed second secretary to the British Embassy in Washington, a post from which he was sent home after repeated misbehaviour. Although not at this stage under suspicion, Burgess nevertheless accompanied Maclean when the latter, on the point of being unmasked, fled to Moscow in May 1951.

Burgess's whereabouts were unknown in the West until 1956, when he appeared with Maclean at a brief press conference in Moscow, claiming that his motive had been to improve Soviet-West relations. He never left the Soviet Union; he was often visited by friends and journalists from Britain, most of whom reported on a lonely and empty existence. He remained unrepentant to the end of his life, rejecting the notion that his earlier activities represented treason. He was well provided for materially, but as a result of his lifestyle his health deteriorated, and he died in 1963. Experts have found it difficult to assess the extent of damage caused by Burgess's espionage activities, but consider that the disruption in Anglo-American relations caused by his defection was perhaps of greater value to the Soviets than any information he provided. Burgess's life has frequently been fictionalised, and dramatised in productions for screen and stage.

My published books: