Queer Places:

Yale University (Ivy League), 38 Hillhouse Ave, New Haven, CT 06520

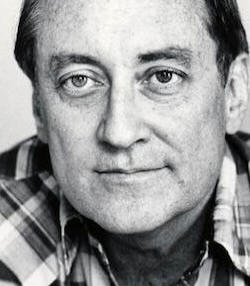

George Selden Thompson (May 14, 1929 – December 5, 1989) was an American author. Known professionally as George Selden, he also wrote under the pseudonym Terry Andrews. He is best known for his 1961 book The Cricket in Times Square, which received a Lewis Carroll Shelf Award in 1963[1] and a Newbery Honor.[2]

George Selden Thompson (May 14, 1929 – December 5, 1989) was an American author. Known professionally as George Selden, he also wrote under the pseudonym Terry Andrews. He is best known for his 1961 book The Cricket in Times Square, which received a Lewis Carroll Shelf Award in 1963[1] and a Newbery Honor.[2]

Terry Andrews is the pseudonym under which was published one of the most remarkable queer books of the twentieth century. At once disturbing and exhilarating, emotionally wrenching and hilariously funny, scathingly iconoclastic and genuinely moving, The Story of Harold (1974) has become a cult classic even as it has mostly languished out of print, its author's identity until recently a mystery. Set in New York and narrated in the first-person by a children's book author named Terry, the novel recounts six months in the life of a death-obsessed bisexual involved with a respectable girlfriend, Anne, whom he introduces to the pleasures of cunnilingus; a handsome, masochistic, married doctor, Jim Whitaker, whom Terry loves desperately but who pointedly disavows any romantic feelings for him; a "fire freak," Dan O'Reilly, who wants to be burnt alive; and a deeply alienated little boy, Bernard, who responds only to Harold, the hero of Terry's children's books. The novel's success is due largely to Andrews' superb control of the narration and his depiction of New York in the late 1960s in the midst of the sexual revolution. Terry recounts all the details and entanglements of his complicated life, and all the despair beneath his comic adventures, in a voice that is both sardonic and sincere. Edmund White has described Terry's voice as "the voice of the first gay liberation generation: romantic and sexual, unguilty and explicit, non-judgmental and appreciative, grittily urban and, at the same time, operatic and verging on hysterical self-dramatising." Whether describing the intricacies of fisting or rhapsodizing about the glories of Richard Strauss, Terry speaks wittily, honestly, and sometimes heartbreakingly.

The Story of Harold appeared in the same year as Patricia Nell Warren's The Front Runner. But whereas Warren's wholesome and uplifting novel managed to become an international best-seller by articulating the aspirations and ideals of the burgeoning gay liberation movement, the more sophisticated but much darker Story of Harold created only a mild stir, then dropped out of print. Its sex scenes too graphic and extreme, its narrator a sexual anarchist rather than a poster boy for gay liberation, The Story of Harold failed to capture the attention of the mass of gay men and lesbians in search of positive representations of themselves and their lives. Even when the book was reprinted in a Bard paperback in 1980 and received the enthusiastic endorsement of gay critic Karl Keller in The Advocate, The Story of Harold did not achieve the wide readership it deserved. When viewed from the perspective of the AIDS crisis in the mid- to late-1980s, the novel must have seemed terribly self-indulgent, featuring as it does not only a protagonist who longs for his own death, but also a character who wants to die in an eroticized suicide. By the end of the novel, however, the obsession with death is replaced by a commitment to life. Indeed, the novel traces the unsentimental journey of its protagonist from a desirer of death to an affirmer of life. Key to the transformation is Harold, the beguiling hero of Terry's children's stories and poems, a leprechaun-like figure who possesses magic powers and a host of curious friends and acquaintances (often modeled on Terry's sexual partners). In enlisting the stories of Harold to teach Bernard some crucial life lessons, Terry eventually comes to an epiphany of his own: "Absurd Three-Legged Impossible God--is this the story you have to tell: it is not possible not to live?" Despite the fact that The Story of Harold has only infrequently been in print since its original publication, it has nevertheless attracted a discerning and appreciative readership. In the Publishing Triangle's June 1999 selection of "The 100 Best Gay & Lesbian Books" by an all-star panel of lesbian and gay writers, including Dorothy Allison, David Bergman, Christopher Bram, Michael Bronski, Samuel Delany, Lillian Faderman, Mariana Romo-Carmona, Sarah Schulman, and Barbara Smith, The Story of Harold was ranked surprisingly high. At number 47, it placed ahead of many much better known works. In his recent appreciation of the novel, Edmund White observes that "This is one of the strangest books I've ever read, probably because it combines elements that never before or since appeared together." White concludes that "The Story of Harold is a remarkable period piece that reminds us that the 1970s was a period far more sophisticated and humane than our own." The Story of Harold not only captures the rhythm of life in New York City in the 1970s for many educated, affluent, gay and bisexual men, but it also conveys, without ever being moralistic or didactic, the emptiness and despair that the era's sexual revolution sometimes masked. For all his prowess as a sexual athlete, Terry finds his existence meaningless until he is faced with the challenge of teaching a sad little boy the incalculable value and possibilities of a positive engagement with life.

Upon its publication and subsequent reprint, Terry Andrews was identified only as "the pseudonym of a well-known author of children's books who lives in New York City." The elusive author of The Story of Harold, it has recently been revealed, is George Selden Thompson, who under the pseudonym George Selden was indeed a very successful author of children's books, winning a Newbery Honor Award for his most celebrated story, The Cricket in Times Square (1961). Selden's cricket, which was also featured in several sequels, bears obvious resemblances to Andrews' Harold.

George Selden Thompson was born in Hartford, Connecticut on May 14, 1929 and educated at Loomis School and Yale University, where he studied English and classical literature. Although he travelled to Europe periodically, he spent most of his life in New York.

He died on December 5, 1989. Sponsor Message. Thompson once observed that "It is difficult to write about one's self. I would much rather write about small animals--good and bad--small children--good and bad--than about a middle-aging author." But what teases one out of thought is the idea that in The Story of Harold Thompson made of the life of "a middle-aging author" a lasting contribution to glbtq literature.

My published books: