Queer Places:

Harvard University (Ivy League), 2 Kirkland St, Cambridge, MA 02138

853 3rd Ave, New York, NY 10022

1364 6th Ave, New York, NY 10019

Pierre Hotel, 2 E 61st St and Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10065

Lunt‐Fontanne Theater, 205 W 46th St, New York, NY 10036

Parsons School of Design, 66 5th Ave, New York, NY 10011

The Art Students League of New York, 215 W 57th St, New York, NY 10019

Edward Melcarth (January 31, 1914 - December 14, 1973) was an American

artist, whose romantic pictures showed the influence of Renaissance painters.

Melcarth dared to live as an openly homosexual man and did not hide his support for communism.

He did murals for the Oval Room of the Pierre Hotel and the ceiling of

the Lunt‐Fontanne Theater. He exhibited widely in New York City and abroad,

and taught at the Parsons School of Design, the Educational Alliance and the

Art Students League. His awards included a grant from the Institute of Arts

and Letters in 1951, and its Childe Hassam purchase award in 1965, the Altman

prize of the Chicago Art Institute in 1950, first prize for figure from the

National Academy of Design in 1964 and its Thomas B. Clarke award in 1969.

Edward Melcarth (January 31, 1914 - December 14, 1973) was an American

artist, whose romantic pictures showed the influence of Renaissance painters.

Melcarth dared to live as an openly homosexual man and did not hide his support for communism.

He did murals for the Oval Room of the Pierre Hotel and the ceiling of

the Lunt‐Fontanne Theater. He exhibited widely in New York City and abroad,

and taught at the Parsons School of Design, the Educational Alliance and the

Art Students League. His awards included a grant from the Institute of Arts

and Letters in 1951, and its Childe Hassam purchase award in 1965, the Altman

prize of the Chicago Art Institute in 1950, first prize for figure from the

National Academy of Design in 1964 and its Thomas B. Clarke award in 1969.

Melcarth was born Edward Epstein to Jewish parents in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1914. After his father died, his mother, whose family discouraged her from becoming an opera singer, remarried a wealthy British aristocrat. Edward, who would reject religion and change his surname to that of an ancient Phoenician god, was educated at the Chelsea Art School in London and at Harvard University; later he studied art in Boston with the German-born painter Karl Zerbe.

The historian Jonathan Coleman, a former teacher of gender studies at the University of Kentucky and the founding director of the locally based Faulkner Morgan Archive, noted, “Melcarth was in Europe in the late 1930s, where, in Venice, he saw a Tintoretto exhibition that, for a young artist who had worked his way through Cubism, came as an epiphany; in his own art, he crafted a vision of a world that perhaps was too beautiful to exist. With their idealized male bodies and often large formats, his paintings represented what he called ‘Social Romanticism.’” Melcarth once stated that “Social Romanticism attempts to describe man’s idealized view of himself using the techniques closer to the Renaissance”; it took ordinary subjects and rendered them “extraordinary.” He added, “There can be no separation between form and content[;] the two are one.”

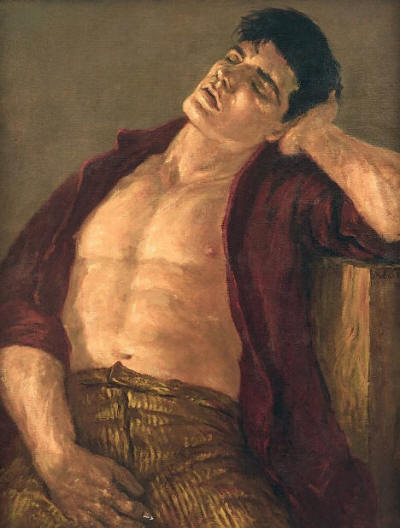

Edward Melcarth, “Junkie with Open Shirt” (no date), oil on canvas, 40.5 x 30.25 inches, The Forbes Collection (photo courtesy of University of Kentucky Art Museum)

.jpg)

Photo taken by the photographer Melcarth, in Venice, who gifted it to his friend Bruno Zanin

Bronze Head of Tom Irwin from Estate of Virgil Thompson by Edward Melcarth (28 cm. Ht)

Melcarth was active on New York’s burgeoning, post-World War II art scene; his work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1940s and at Manhattan galleries over a decades-long timespan, and he knew just about everyone: Peggy Guggenheim (for whom he designed a famous pair of bat-shaped sunglasses); Tennessee Williams; Gore Vidal; and the multimillionaire art collector and Forbes magazine publisher, Malcolm Forbes; his circle also included many other artists as well as countless, now nameless hustlers, sailors, beach bums, and representatives of working-class “trade” who posed for his pictures and with whom he had sex.

Coleman, who wrote his University of Kentucky doctoral dissertation about same-sex prostitution in London from 1885 to 1957, oversees an archive named for the gay, Kentucky-born artists Henry Faulkner and his student, Robert Morgan. Faulkner, a close pal (and maybe also a lover) of the playwright Tennessee Williams, made colorful, stylized still lifes and was known for turning up at art shows with a bourbon-drinking goat. Morgan makes mixed-media assemblages, some of which have incorporated photographs and personal mementos from young gay men who were the victims of AIDS, alcoholism, or drug abuse. The archive houses Faulkner’s and Morgan’s personal papers, photos, and gay-related miscellanea; its mission, Coleman explained, is to document the contributions to Kentucky’s history, culture, and society of LGBT persons who would otherwise be written out of the region’s mainstream history.

Coleman’s research has shown that Melcarth, Faulkner, and the photographer Thomas Painter lived together in New York for some time during the decades following WWII. They shared friends, artistic interests — and sexual partners, too. Coleman said, “Painter was one of the research subjects who provided testimonials about his own and his homosexual associates’ sexual activities to the pioneering sexologist Alfred Kinsey. His reports were detailed, and from them one can learn something about Melcarth, whose appetite for sex was rapacious.” The faces of several of the hustlers, blue-collar workers, and other acquaintances who posed for Melcarth and presumably also kept his bed warm are the subjects of his small-format, oil-on-canvas paintings.

In the essay Painter wrote for Kinsey in 1944, he related Melcarth’s sexual sojourn in the Middle East, where he briefly resided in the early 1940s. According to Painter, trying to avoid being drafted into the Army, Melcarth left the United States to move to Iran where he worked as a truck driver for a construction company building roads in the region. Painter knew Melcarth as a sexually adventurous and highly promiscuous “queer” with the similar taste for young and muscular “proletarian” men and, in the essay, recounted his homosexual exploits abroad. Painter emphasized that, as witnessed by Melcarth, commercially based sexual contacts between men were “a settled part of the social pattern” in Iran but remarked about Melcarth’s discontent with his partners’ too young ages. In fact, Melcarth was hardly the only homosexual foreigner in the region; there were many European and American “queers” who “made quite a colony, all with house boys and the services of the local pimps.” In the 1950s, escaping the politically repressive atmosphere in the United States, Melcarth, who was a member of the Communist Party and was in constant trouble with the FBI, also regularly traveled to Venice where he found a welcoming community of homosexual expatriates and enjoyed cheap and easy-to-arrange sexual relations with the local young men.

In the late 1960s, Melcarth left New York and settled in Venice, where he focused on making sculpture and died in 1973. At some point during his New York years, he had met Malcolm Forbes, who became a regular collector-patron and, after Melcarth’s death, acquired a large quantity of his works. After Forbes died in 1990, it became publicly known that he had lived as a closeted gay man. His written correspondence with Melcarth was friendly and cordial, and mainly concerned his purchases of the artist’s works.

Melcarth died on December 14, 1973, in Venice, where he lived. His age was 59.

My published books: