Queer Places:

Eton College, Windsor SL4 6DW, UK

University of Cambridge, 4 Mill Ln, Cambridge CB2 1RZ

Elshieshields, Lockerbie DG11 1LY, UK

James Cochran Stevenson Runciman aka Sir Steven Runciman (July 7, 1903 – November 1, 2000)

was an historian,

aesthete and traveller. He died aged 97 in 2000. He was the pre-eminent British

specialist of the Byzantine empire and of the crusades. His three-volume A

History Of The Crusades, published between 1951 and 1954, set out to exemplify

his belief that the main duty of the historian was "to attempt to record, in

one sweeping sequence, the greater events and movements that have swayed the

destinies of man," and show that history's aim was to give a deeper

understanding of humanity. He aimed as much at a non- specialist audience as

at fellow academics.

James Cochran Stevenson Runciman aka Sir Steven Runciman (July 7, 1903 – November 1, 2000)

was an historian,

aesthete and traveller. He died aged 97 in 2000. He was the pre-eminent British

specialist of the Byzantine empire and of the crusades. His three-volume A

History Of The Crusades, published between 1951 and 1954, set out to exemplify

his belief that the main duty of the historian was "to attempt to record, in

one sweeping sequence, the greater events and movements that have swayed the

destinies of man," and show that history's aim was to give a deeper

understanding of humanity. He aimed as much at a non- specialist audience as

at fellow academics.

Runciman was the second son of Walter Runciman (later Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford), who was descended from the mid 18th- century Scottish painter, Alexander Runciman. His father was a member of Asquith's cabinet and his mother, Hilda Stevenson, was MP for St Ives. His older brother was Walter Leslie Runciman, 2nd Viscount Runciman of Doxford. Steven himself always welcomed the fact that, as the younger son, he was not obliged to go either into politics or the family's shipping business. Indeed, an academic career was foreshadowed by his precocious ability to read French at three, Latin at six, Greek at seven and Russian at 11.

He won a scholarship to Eton, where a combination of an early interest in Greece and medievalism led naturally to his study of Byzantium. His school friends included Cyril Connolly, George Orwell and "Puffin" Asquith, the prime minister's son.

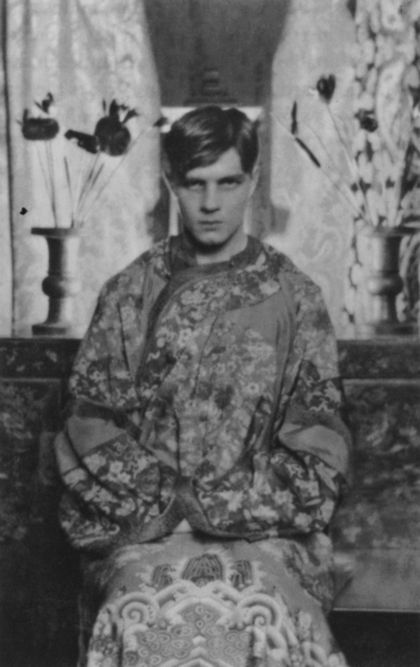

In 1921, a further scholarship took him to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he began to demonstrate an elegant and fashionable aestheticism by papering his rooms with a French grisaille wallpaper depicting Cupid and Psyche, and being photographed by his friend, Cecil Beaton, with a parrot poised on his ringed finger. Through his school friend George Rylands, he was introduced to John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf, and got to know the Bloomsbury group.

After taking a first in history, Runciman became a research student of the notoriously elusive JB Bury, the first British historian to take Byzantium seriously. He artfully discovered the regius professor's regular habit of taking an afternoon walk along the Backs, and was thus able to manoeuvre Bury into giving him unofficial tutorials.

Following an attack of pleurisy - and his doctor's prescription that his best chance of recovery would come from a long sea voyage - he went to China, arriving in the middle of the civil war. But this did not prevent him from befriending the last Chinese emperor, with whom he played piano duets.

In 1924, Runciman made his first trip to Greece, was enchanted by the Byzantine town of Monemvasia and, later, by the old city of Istanbul. On his return to Cambridge, he concentrated on his fellowship thesis, with pioneering investigations into Armenian and Syriac sources, which, in 1929, resulted in his first book, The Emperor Romanus Lecapenus. After that, in quick succession, came The First Bulgarian Empire and Byzantine Civilisation.

Runciman had gone back to Trinity in 1927 to teach and hold a fellowship until 1938. His first pupil had been Guy Burgess, whom he remembered for his intellectual brilliance and his dirty fingernails. His last pupil was Donald Nicol, who became Koraes professor of modern Greek and Byzantine history at London University. Meantime, his travels had taken him to Jerusalem and Thailand, with several more visits on foot and muleback to Greece and Turkey.

When his grandfather died in 1938, Runciman could afford to give up his fellowship, and take George Trevelyan's advice to leave Cambridge and concentrate on his writing. By a happy chance, the war took him back to the countries of his choice, first as press attaché in Sofia in 1940, then to Cairo and Jerusalem for the Ministry of Information, and finally to Istanbul for three years as professor of Byzantine art and history. This gave him the opportunity to follow the tracks of the crusaders and plan his History Of The Crusades - as well as visiting Syria and becoming an honorary whirling dervish.

Immediately after the war, Runciman willingly accepted the offer to direct the work of the British Council in Greece. During the next two years, assisted by Paddy Leigh Fermor and Rex Warner, this remarkable triumvirate endeared themselves to the Greeks in a manner that has never been rivalled. In Athens, Runciman became a well-known figure in the smart Kolonaki set ("the good bandit families", as he characteristically called the descendants of the leaders of the Greek war of independence) and was a friend of George Sepheriades, the diplomat whose poetry, under the name of Sepheris, later won a Nobel prize. In his spare time, he improved his collection of icons, tanagras (figurines) and Edward Lears.

A fter the publication, in 1947, of The Medieval Man- ichee, a still unchallenged study of the Christian dualist heresy, Runciman returned to Britain to start work on the crusades, dividing his time between his house in St John's Wood, London, and the isle of Eigg, off the Scottish coast, which his father had bought in 1926. From 1951 to 1967, he was chairman of the Anglo-Hellenic League, which he nicknamed "the Anglo-Hell".

His reputation was triumphantly established when A History Of The Crusades was published in three volumes, between 1951 and 1954. Praising the pace and style of its narrative history, some critics even compared its author to Macaulay.

The Eastern Schism was published in 1955, and The Sicilian Vespers in 1958. This was the year in which Runciman was knighted, and in 1961 he was made a knight commander of the Greek Order of the Phoenix. As part of his continuing revival of interest in Byzantium, The Fall of Constantinople: 1453, appeared in 1965, The Great Church In Captivity in 1968, The Last Byzantine Renaissance in 1970, The Orthodox Churches And The Secular State in 1972, and Byzantine Style And Civilization in 1975.

When a street was named after him in Mistra, his expression of gratitude took the form of a book, published in 1980, about the Byzantine capital of the Peloponnese.

When Eigg was sold in 1966, he quickly moved to Elshieshields, a border tower in Dumfrieshire. Indeed, throughout his long and peripatetic life, he had always known that his roots were in Scotland. This became his last home, where he happily entertained both old and new friends, introducing them to his collection of 18th- and 19th-century musical boxes, worry beads, a hubble bubble, the Alexander Runcimans and Edward Lears, the limericks as well as the watercolours.

My published books: