Queer Places:

Holy Sepulchre Cemetery

Rochester, Monroe County, New York, USA

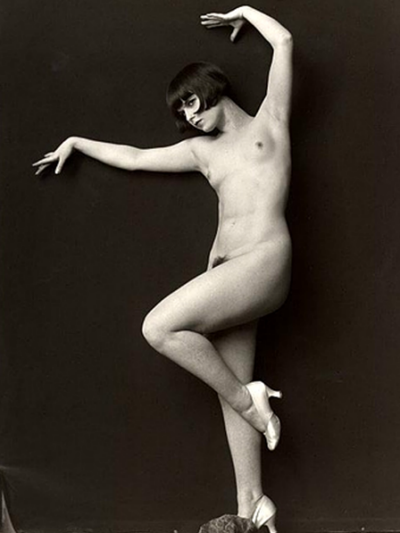

Mary Louise Brooks (November 14, 1906 – August 8, 1985), known professionally as Louise Brooks, was an American film actress and dancer during the 1920s and 1930s. She is regarded today as a Jazz Age icon and as a flapper sex symbol due to her bob hairstyle that she helped popularize during the prime of her career.[1][2][3]

At the age of fifteen, Brooks began her career as a dancer and toured with the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts where she performed opposite

Ted Shawn.[4] After being fired, she found employment as a chorus girl in George White's Scandals and as a semi-nude[5] dancer in the Ziegfeld Follies in New York City.[5][6] While dancing in the Follies, Brooks came to the attention of Walter Wanger, a producer at Paramount Pictures, and was signed to a five-year contract with the studio.[7][5] She appeared in supporting roles in various Paramount films before taking the heroine's role in Beggars of Life (1928).[8] During this time, she became an intimate friend of actress

Marion Davies and joined the elite social circle of press baron William Randolph Hearst at Hearst Castle in San Simeon.[9][10]

Mary Louise Brooks (November 14, 1906 – August 8, 1985), known professionally as Louise Brooks, was an American film actress and dancer during the 1920s and 1930s. She is regarded today as a Jazz Age icon and as a flapper sex symbol due to her bob hairstyle that she helped popularize during the prime of her career.[1][2][3]

At the age of fifteen, Brooks began her career as a dancer and toured with the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts where she performed opposite

Ted Shawn.[4] After being fired, she found employment as a chorus girl in George White's Scandals and as a semi-nude[5] dancer in the Ziegfeld Follies in New York City.[5][6] While dancing in the Follies, Brooks came to the attention of Walter Wanger, a producer at Paramount Pictures, and was signed to a five-year contract with the studio.[7][5] She appeared in supporting roles in various Paramount films before taking the heroine's role in Beggars of Life (1928).[8] During this time, she became an intimate friend of actress

Marion Davies and joined the elite social circle of press baron William Randolph Hearst at Hearst Castle in San Simeon.[9][10]

In the summer of 1926, Brooks married Eddie Sutherland,[103] the director of the film she made with W. C. Fields,[28] but by 1927 had become infatuated[104] with George Preston Marshall, owner of a chain of laundries and future owner of the Washington Redskins football team,[103] following a chance meeting with him that she later referred to as "the most fateful encounter of my life".[105] She divorced Sutherland, mainly due to her budding relationship with Marshall, in June 1928.[106] Sutherland was purportedly extremely distraught when Brooks divorced him and, on the first night after their separation, he attempted to take his life with an overdose of sleeping pills.[107] Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, Brooks continued her on-again, off-again relationship with George Preston Marshall which she later described as abusive.[102] Marshall was purportedly "her frequent bedfellow and constant adviser[e] between 1927 and 1933."[34][102] Marshall repeatedly asked her to marry him but, after learning that she had had many affairs while they were together and believing her to be incapable of fidelity, he married film actress Corinne Griffith instead.[102] In 1925, Brooks sued the New York glamour photographer John de Mirjian to prevent publication of his risque studio portraits of her; the lawsuit made him notorious.[108]

Brooks sued the glamour photographer John de Mirjian to prevent him from distributing his nude portraits of her.[108]

Dissatisfied with her mediocre roles in Hollywood films, Brooks went to Germany in 1929 and starred in three feature films which launched her to international stardom: Pandora's Box (1929), Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), and Miss Europe (1930); the first two were directed by G. W. Pabst.

In 1933, she married Chicago millionaire Deering Davis, a son of Nathan Smith Davis, Jr., but abruptly left him in March 1934 after only five months of marriage, "without a good-bye... and leaving only a note of her intentions" behind her.[109] According to Card, Davis was just "another elegant, well-heeled admirer", nothing more.[109] The couple officially divorced in 1938.

By 1938, she had starred in seventeen silent films and eight sound films. After retiring from acting, she fell upon financial hardship and became a paid escort.[11] For the next two decades, she struggled with alcoholism and suicidal tendencies.[12][13] Following the rediscovery of her films by cinephiles in the 1950s, a reclusive Brooks began writing articles about her film career; her insightful essays drew considerable acclaim.[14][11]

In her later years, Brooks insisted that both her previous marriages were loveless and that she had never loved anyone in her lifetime: "As a matter of fact, I've never been in love. And if I had loved a man, could I have been faithful to him? Could he have trusted me beyond a closed door? I doubt it."[24] Despite her two marriages, she never had children, referring to herself as "Barren Brooks."[110] Her many paramours from years before had included a young William S. Paley, the founder of CBS.[57] Paley provided a small monthly stipend to Brooks for the remainder of her life, and this stipend kept her from committing suicide at one point.[96][11][102]

She published her memoir, Lulu in Hollywood, in 1982.[14][15] Three years later, she died of a heart attack at age 78.[16]

Following Brooks' death, writer Kenneth Tynan asserted that "she was the most seductive, sexual image of Woman ever committed to celluloid. She's the only unrepentant hedonist, the only pure pleasure-seeker, I think I've ever known."[113] By her own admission, Brooks was a sexually liberated woman, unafraid to experiment, even posing nude for art photography,[108][114] and her liaisons with many film people were legendary, although much of it is speculation. Brooks enjoyed fostering speculation about her sexuality,[112] cultivating friendships with lesbian and bisexual women including Pepi Lederer and Peggy Fears, but eschewing relationships. She admitted to some lesbian dalliances,[115] including a one-night stand with Greta Garbo.[116] She later described Garbo as masculine but a "charming and tender lover".[117][118] Despite all this, she considered herself neither lesbian nor bisexual: I had a lot of fun writing Marion Davies' Niece [an article about Pepi Lederer], leaving the lesbian theme in question marks. All my life it has been fun for me. ... When I am dead, I believe that film writers will fasten on the story that I am a lesbian ... I have done lots to make it believable ... All my women friends have been lesbians. But that is one point upon which I agree positively with Christopher Isherwood: There is no such thing as bisexuality. Ordinary people, although they may accommodate themselves, for reasons of whoring or marriage, are one-sexed. Out of curiosity, I had two affairs with girls — they did nothing for me.[119] According to biographer Barry Paris, Brooks had a "clear preference for men", but she did not discourage the rumors that she was a lesbian, both because she relished their shock value, which enhanced her aura, and because she personally valued feminine beauty. Paris claims that Brooks "loved women as a homosexual man, rather than as a lesbian, would love them. ... The operative rule with Louise was neither heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality. It was just sexuality..."[120]

My published books: